A life including political activism and a stint in prison didn’t stop Ethel Smyth’s extensive musical output. Taken from the August 2008 issue.

This is an extract from the article ’Ethel Smyth: A woman of substance’ taken from the August 2008 issue. To read the full article, click here

Smyth was not born into a musical family, and at 18 embarked on a bitter battle with her father to be allowed to study music at a conservatoire. In her memoir Impressions That Remained, she wrote, ‘That night there was a discussion at dinner as to which drawing-room I had better be presented at. Suddenly I announced it was useless to present me at all, since I intended to go to Leipzig, even if I had to run away from home, and starve when I got there.’ She managed to overcome her father’s prejudices and entered the Leipzig Conservatoire in 1877. The next ten years she spent in Europe, soaking up its heady musical atmosphere and gaining critical acclaim for a number of her chamber pieces.

She met both Brahms and Tchaikovsky: the latter gave her encouragement in exploring her own musical identity. In 1890 she moved back to London, where works such as the orchestral Serenade began to build her reputation as a composer, and in 1892 she made her first foray into opera with Fantasio. Smyth spent many years fighting to get the opera its first performance, which finally took place in Weimar in 1898. It was a similar story for her other operas: The Wreckers, for example, was composed between 1902 and 1904, but was not performed in London until 1909, and only then with financial support from a friend of Smyth’s. It did, however, garner her lavish reviews and became her best-known work. By 1902 Smyth had also embarked on her String Quartet in E minor, a work that took her ten years to complete.

But her musical life was to take a back seat to political activities in the following years, and it is the image of a fiery, impetuous and eccentric suffragette that colours the public perception of Smyth. In 1910 she attended a meeting of the Women’s Social and Political Union, and was so moved by the speaker, Emmeline Pankhurst, that she vowed to give up music for two years in order to devote herself to fighting for votes for women. She wrote The March of the Women in 1911, which became the suffragette’s battle anthem. Smyth’s place in the political history books was cemented when in 1912 she joined more than a hundred other women in smashing windows of the homes of opponents to the suffrage movement.

Tales of her prison stay give a vivid picture of her indomitable nature: on one occasion she led an impromptu performance of The March of the Women from her window overlooking the prison yard as the women did their outdoor exercise, conducting their singing with a toothbrush. Her controversial memoirs were also partly to blame for diverting attention from the substance of her music. In several published volumes she wrote of her love for women including the writer and artist Edith Somerville and, most famously, Virginia Woolf, with whom she had an intense friendship. Woolf paints a vivid description of Smyth in a letter she wrote to the composer in 1940: ‘I suppose I told you how I saw you years before I knew you? Coming bustling down the gangway at the Wigmore Hall, in tweeds and spats, a little cock’s feather in your felt, and a general look of angry energy… You reminded me of a ptarmigan – those speckled birds with fetlocks.’

This larger-than-life public persona has always threatened to eclipse Smyth’s talents as a composer. Yet delving into her music reveals a voice capable of power and passion but also depth and surprising fragility. These are works that bear the hallmarks of a brilliant technician who approaches her subject with inventive flair,from the Brahms-influenced lyricism of her early pieces to the neo-Classicism and rhythmic innovation of her mature works. During the 1920s, her music, including her final two operas, Fête galante (1921–2) and the comic opera Entente cordiale (1923–4), at last began to receive numerous performances.

Smyth regularly conducted her own works and was also much in demand as a broadcaster; Smyth’s first compositions for strings date back to her time in Leipzig. These early works are infused with the spirit of the late Romantic German tradition, well structured and bountifully expressive yet laced with her own distinctive charm. The Fanny Mendelssohn Quartet members played in the first CD recordings of her String Quintet op.1 (1883), Violin Sonata op.7 (1887) and two cello sonatas (1880 and 1887) alongside other chamber works by Smyth. Leader Renate Eggebrecht explains why she feels so strongly about championing the work of this bold composer:

‘The way in which Smyth treats the instruments, and lets them all have an individual voice, is always a joy. I find the deep grief of the slow movement of the String Quintet particularly moving. Then there is the mature String Quartet [1912], which is a masterpiece: harmonically rich and full of rhythmic and melodic imagination.’

The quartet’s cellist, Friedemann Kupsa, has particular admiration for the cello sonatas:

‘Smyth was obviously well-versed in the traditional cello repertoire, such as the Arpeggione Sonata by Schubert and the Beethoven sonatas, but her music is totally her own – new, fresh and incredibly appealing.’

Read: Tasmin Little: why I love the music of Ethel Smyth, Clara Schumann and Amy Beach

Topics

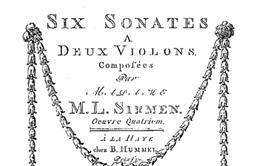

Female violinists of 18th-century England: Portrait of a lady holding a violin

Taking a Regency portrait of an unknown violinist as his starting point, Kevin MacDonald investigates the lives and careers of Louise Gautherot and other female violinists of Georgian England

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Ethel Smyth: life as a suffragette and composer

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

No comments yet