Ahead of a performance at 3 Choirs Festival, violist Shiry Rashkovsky examines how the musically philanthropic efforts of Lionel Tertis and Ralph Vaughan Williams aided Jewish refugees of World War II

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

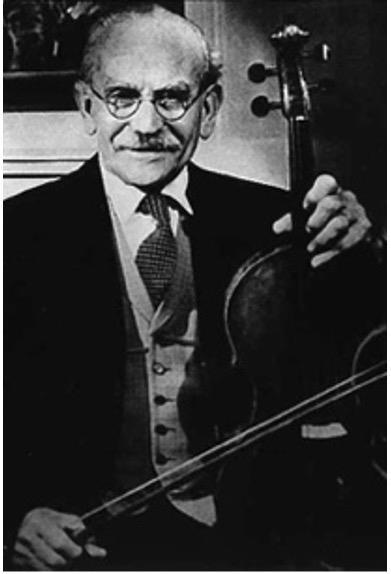

‘A colleague once accused me of trying to split hairs in groping for Utopia,’ Lionel Tertis once wrote. ‘But why not? I see nothing against endeavouring to attain the impossible, however inadequate our efforts may be towards that goal.’ While it is well known that Tertis was an essential player in advocating for the viola’s reception as a peer to the violin and cello, there is an equally important story to be told about his keen aspirations to help those in dire need in World War II, and the unique kinship he found with his contemporary Ralph Vaughan Williams, both musical and philanthropic.

Tertis faced significant structural challenges in his personal and musical life. While his childhood was musically rich, his early years were marked by the poverty well known to the community of Eastern European Jewish refugees who had escaped the increasingly frequent pogroms of the early 20th century and settled in London’s East End. His father was the local cantor, sharing his vocal talent with the Jewish congregation as he led them in prayer, and naturally brought his work home, practising beside the young Lionel. But these were challenging times; Tertis later described the environs of his home on the edge of Petticoat Lane as ‘so squalid that [he] was lucky to survive it’.

Entrepreneurial in spirit, he took to working life at a young age, recounting in his autobiography The Viola and I the challenging conditions of jobbing musicians, which for him involved busking at the waterfront to make ends meet and relying on hot potatoes in his pockets to warm his hands when concert venues were not heated; he applied the same ingenuity to raising funds to study the violin at the Royal Academy, writing to Lionel de Rothschild and suggesting with chutzpah that their shared name was grounds for sponsorship, which resulted in a cheque for £10 (today’s £1300).

His pursuit of the viola may seem odd when considering its lowly position in the music world of the early 1900s; indeed, as he recalled towards the end of his life, ‘so casual was my discovery of my mission in life, of that beautiful, soon to be beloved viola, to which I was to devote the rest of my days’. A friend at the Academy wanted to start a quartet but had no violist, leading Tertis to take up the instrument, and, in doing so, withstand much mockery. The viola was then considered the purview of violinists deemed insufficiently competent to play professionally, a reputation which led Tertis him to describe it affectionately as the ‘Cinderella’ of instruments, wrongly looked down upon and with so much to offer.

Little thought had been given to the viola as a solo instrument, or even an essential participant in the orchestra or chamber ensemble, and the violas available to play on were often enormous and unwieldy. Tertis identified this deficiency and devoted himself to rectifying it, proselytising for the viola as an equal (or, dare I dream, superior) to the violin and cello, creating countless arrangements and penning his own works, and developing the ‘Tertis model’ instrument which accommodates many body sizes and facilitates virtuosic playing, and therefore writing, for the instrument, ushering in a new era of regard for the viola.

Read: 10 playing tips by violist Lionel Tertis

Read: From the archive: the 1717 Montagnana viola once belonging to Lionel Tertis

Key to Tertis’s work establishing the viola as a solo instrument were his relationships with composers in Britain. His influence on his contemporaries was far-reaching; he names Gustav Holst, T.F. Dunhill, Richard Walthew and Percy Grainger (while Grainger was living in England) in The Viola and I as just a few of those whose pieces he premiered, and his work as a pedagogue reached the next generation, notably violist and composer Rebecca Clarke; and indirectly, much further afield, Ernest Bloch.

One in particular stands out: Ralph Vaughan Williams. Jessica Duchen, renowned musicologist and journalist with whom I developed the narrated concert Seeking Utopia on the subject of this unique friendship, suggests that Vaughan Williams found in Tertis a special kinship, rooted perhaps in his childhood dream of becoming an orchestral violist, thwarted early on by his family’s belief that the only appropriate instrument for a child of his social standing and class was the organ. Having found a friend so devoted to the instrument he loved so dearly, Vaughan Williams composed and dedicated his Flos Campi (1925) and Suite for Viola and Piano or Orchestra (1933-1934) to Tertis, both representing some of the first major British works for solo viola and large accompanying ensemble, which I personally consider deeply meaningful works, and a joy to programme.

While their friendship transcended socio-economic and religious barriers to generate some of the most beautiful and profound viola music of the time, I would venture to suggest that even more significant, and certainly less well documented, was their mutual philanthropy and dedication to the cause of Jewish refugees of World War II. Despite their diverging experiences of the war, naturally informed by their opposite positions on the religious, class and wealth spectra, they both threw themselves into support efforts. Tertis utilised his musical talent and status, coming out of his injury-induced retirement to undertake a recital tour of British cathedrals in aid of London’s Distress Fund which supported those who were injured and unhoused by the war, and playing frequently in Myra Hess’s National Gallery concerts for the Musicians Benevolent Fund, which Vaughan Williams assisted in programming and administering, as the Blitz audibly raged on.

Capitalising on his social and financial wealth, Vaughan Williams became vice-chairman of the Dorking and District Refugee Committee; chairman of the Home Office Committee for the Release of Interned Alien Musicians; he paid for music teacher training for composer Dr Gerhard Pinthus, enabling his release from a concentration camp; backed pianist Peter Stadlen’s application for a work permit, facilitating a career which led him to become music critic of The Telegraph; co-signed a letter to The Times with E.M. Forster appealing for the improvement of conditions of Jews interned as ‘enemy aliens’; the list goes on, so much so that his anti-Nazi reputation led to the banning of his music in Germany.

When playing Vaughan Williams’s Suite for Viola, I am transported to the years of its composition, on the cusp of some of the darkest years of Europe’s history. It is a gift to think of the friendship between composer and dedicatee; and while my relationship to those years as an Ashkenazi Jew will never be straightforward, it touches me to know how the story of Vaughan Williams and Tertis’s contribution ends.

Celebrating the friendship between Tertis and Vaughan Williams, violist Shiry Rashkovsky, narrator Jessica Duchen and pianist Viv McLean will perform Seeking Utopia at the 3 Choirs Festival on 27 July 2023. Find out more here: https://3choirs.org/events/seeking-utopia

The trio will also perform the programme at Barnes Music Society – St Mary’s Church, Barnes on 22 February 2024, 7.30pm.

Read: Great string players of the past: Joshua Bell on Eugène Ysaÿe

Read: 4 reasons why I love Vaughan Williams - violist Philip Dukes

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

1 Readers' comment