Strad readers submit their problems and queries about string playing, teaching or making to a panel of experts

In the next of the series, a violin teacher describes an inability to bend the second (large) joint of the left-hand fourth finger - an issue she has encountered in several of her students.

Do you have a burning question about string playing, teaching or making that you need answering by people who really know? Email us at thestrad@thestrad.com

The dilemma Over the years I have had several students who seem unable to bend the large knuckle of the fourth finger in the left hand. It is a fairly common trait in young students and I always try to have them work on curving the 'pinky'. However, I have also had advanced students who still play with the locked pinky, and it often doesn't affect their sound, vibrato or intonation adversely. Trying to change this habit can be impossibly frustrating for a very advanced student. I started to notice among my colleagues in symphony that there were some players who play very well with a 'locked' middle knuckle in their fourth finger.

My question is: are some string players' hands and fingers just built differently, so that the curve will never work for them? And how important is it to try to change this habit?

BARBARA MCDOUGALL, VICTORIA, BC, CANADA

STEPHEN CHIN The curvature of the fourth finger is certainly one of the toughest aspects of violin technique to correct. Although I have seen and heard both advanced and professional players perform reasonably well with a locked fourth finger, from my experience I believe that once it is unlocked, progress can be accelerated, owing to less tension and greater tactility in the left hand. I have also found that working on unlocking the double joints in the fourth finger makes everything to do with left-hand technique much more achievable. Even from birth, one can see how a baby’s fingers, including the fourth, naturally wrap around anything that comes within reach. Indeed, throughout our lives we use our hands this way most of the time.

Once it is clear that the fourth finger needs attention, I work with the student to set the base of the first finger under the neck and bring the base of the fourth finger close enough to the side of the neck so that the finger can be placed on the fingerboard already in the curved position. Encouraging a relaxed thumb, placing the wrist joint out gently and ensuring that the left arm adjusts its position for each string level are also important factors in achieving a reliable and flexible left-hand frame.

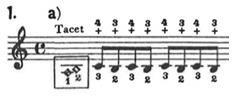

As far back in 1751, in his book 'The Art of Playing on the Violin', Geminiani suggests the ideal setting of the hand using these notes:

Assuming all the fingers are curved enough to clear the adjacent strings, the simple up-and-down movement of the fourth finger on the fingerboard without the bow for a couple of minutes daily, works wonders in allowing it to get used to this optimum playing position. The playing of harmonics and the left-hand pizzicato of open strings with the fourth finger also assist in the early stages of playing or correction.

For more advanced players, short trill studies similar to Kreutzer Etude no.16, which specifically targets the fourth finger, are indispensable. Shifting, stretching and left-hand pizzicato exercises such as those found in 'The Artist’s Technique of Violin Playing' (Dounis, 1921) are also great in assisting more advanced level students gain greater flexibility and strength in the left hand by placing more demands on the way the fourth finger interacts with the other parts of the hand:

Although all of this can be quite challenging for students that need to change the habit of a locked ‘pinky’, I have seen time and time again that the rewards far outweigh the demands. My suggestion for teachers is to set aside a few weeks of playing easier works and fun duets so that the student can gradually become accustomed to the new left-hand position.

SHI-HWA WANG Double-jointedness is really called joint hypermobility (JH). This means that double-jointed people can, willingly or not, bend their fingers with unusual or extra flexibility. Teachers may find that double-jointed students have two annoying ‘habits’: bending their right pinky backwards on a bow hold; and bending the last two finger joints on their left hand backwards.

Studies show that double-jointed players have a higher risk of arthritis in their finger joints. Secondly, they require more control over their muscles to do a ‘sustained’ curving of the fingers than a person without JH. The latter really puts a strain on double-jointed students: it causes them not to want to do 'the right thing’.

Patience and sympathy are paramount when dealing with this issue. If the student collapses their left-hand fingers, certain intervals will become a problem – such as going from the fourth to the first finger, both when shifting upwards and crossing strings. The collapsed fourth finger is in the way and has to be lifted before using the first finger. Similarly, it is hard for students with JH to play double-stops – say a 3rd that requires the second and fourth fingers.

When a student straightens the pinky joints instead of forming a nicely curved shape, it is invariably because they are bending the pinky from their lowest finger joint, where the finger meets the palm. If they instead use the joint lower down (which is hiding in the palm towards the carpals), the pressure on the pinky’s last two joints will be released. Finally, teachers should explain the physical nature of JH fingers and thumbs to their double-jointed students, which will make it easier for both to overcome and avoid the ‘bad habits’.

MAUREEN SMITH While thinking about this problem, I realised that two of my own pupils also suffer from it – and I even noticed it on myself! I was working with one of my students as both of her knuckles were flat, not just the middle one, and I advised her to place all the fingers on the string, and then try to raise and lower her fourth finger several times independently, while attempting to keep it curved at all times.

I think the important factor is whether the student’s vibrato works, and if the finger is generally flexible. My own finger bends nicely when I vibrate and there is no tension. I would also add that when doing the above exercise, the finger needs to be lifted from the base joint.

Regarding the issue of the fourth finger not bending, I would agree that it doesn't matter if it has no effect on the finger’s strength, but most importantly on the vibrato. I have seen players who look like they have a ‘locked’ finger (with a very flat finger position), but when it comes to vibrating you can clearly see the middle joint being flexible. It happens a lot with double-jointed students.

I think it is very difficult to change this. Your idea of lowering the finger with the other fingers on the string is a good one. Perhaps try starting on the E string, where the fourth finger is less likely to be flat, and attempt to keep the left hand as close to the string as possible – in other words, keep the base of the fourth finger very near the fingerboard, therefore forcing the finger to bend. Then move on to the other strings, keeping the same position of the hand.

Stephen Chin is a lecturer at Queensland Conservatorium of Music, director of strings and orchestras at Brisbane Grammar School, and national president of the Australian String Teachers Association: www.austa.asn.au

Shi-Hwa Wang is professor of violin and viola at Weber State University, UT, US: http://faculty.weber.edu/swang

Maureen Smith teaches at the Royal Academy of Music, where she was made an honorary associate in 1995: www.ram.ac.uk

Do you have a burning question about string playing, teaching or making that you need answering by people who really know? Email us at thestrad@thestrad.com.

Read: Ask the Experts: how to help a student with a short fourth finger

Technique: Left-hand calisthenics

Quick warm-ups to help you improve strength, endurance, flexibilty and control

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Ask the Experts: how to cure a locked left-hand fourth finger

No comments yet