Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

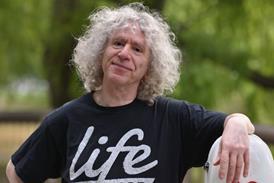

My first encounter of ‘Sonate op. Posthume’ by Maurice Ravel was comparatively recent. Last summer, Keigo Mukawa and I were looking to complete our programme for a performance at Salle Cortot in Paris of both the violin sonatas by Gabriel Fauré and Keigo, a great exponent of Ravel, suggested we include the Posthumous. After reading it through, we immediately agreed and it was only then that, quite serendipitously, we discovered its beautiful connection with Fauré.

Ravel was asked to leave the Paris Conservatoire in 1895, the Conservatoire citing lack of piano proficiency, but upon the advice and encouragement of Fauré, he was readmitted two years later. The Posthumous was most likely written as an exercise for Fauré’s composition class and as Ravel’s first exploration of the form of the sonata. Classmate, George Enescu, and the composer performed it for the group (how I would’ve loved to have been a fly on the wall in those lessons!)

One of the most remarkable elements of the Posthumous for me is that, although we hear influences of the leading French composers of his youth as well as infrequent German references (the class would have studied Wagner in particular), Ravel’s harmonic language was already well developed despite obvious inexperience; it’s evident straight away that this isn’t Debussy or Fauré.

While the reason that the work remained unpublished is unclear, perhaps Ravel wished to clearly define his unique modernist style that he would later champion, of which the Posthumous isn’t, or indeed that he may have wanted to revisit it later. There is certainly material reminiscent of the later Piano Trio, one of the greatest marvels of chamber music. It was, however, left undiscovered and only found in 1975, 38 years after his death - hence the title.

Performing Ravel presents a unique challenge; never to interfere with his work and allowing it to reveal itself organically. He said himself his music was to be ’played, not interpreted’, so remaining totally faithful to his intentions yet making it personal to us is such a delicate balance and much more demanding than flying up and down the fingerboard!

One particular section to highlight is the development; in my opinion the most powerful moment of the work. Beginning serenely, both instruments float around the main theme and he eventually marks the violin ‘bien chanté’, a beautiful performance direction. Constantly building in intensity, the climax occurs when this energy can’t be contained any longer - the piano has short, virtuosic explosions as the violin continues to soar above it until both instruments melt away.

Exploring this music with Keigo, who feels the composer so naturally and with such sincerity, is an enormous joy. Our thanks also to Xavier Carrère of Radio France for the invitation to have played for the programme in this special year for Maurice Ravel.

The performance was filmed on 26 April 2025 at Théâtre de l’Alliance Française for the Générations France Musique, le Live programme.

De Sá photo credit: Frances Marshall Photography.

Read: French connection: the Ispir brothers following in the footsteps of the Capuçons

Read: Sibelius Violin Concerto, then and now

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet