A castle setting, an enticing top prize and some highly promising string players were what Tom Stewart encountered at the Windsor Festival International String Competition final in March

One warm and sunny day in the spring, the swans of the River Thames gleaming while crowds of golden daffodils bloomed around them, I arrived at the final of the Windsor Festival International String Competition. Windsor Castle, around 25 miles upstream from London and sitting atop the hill it has occupied for almost a thousand years, is home to the British royal family and, once every two years, also to the competition that this year offered a top prize of £5,000; a concerto performance with the Philharmonia Orchestra; a contemporary bow to the value of £5,000; a CD recording on British label Champs Hill Records; and recital opportunities, including one at William Walton’s former home on the Italian island of Ischia.

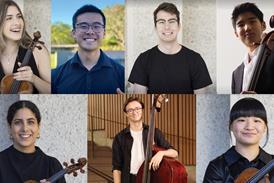

Twelve semi-finalists from as far afield as Mexico, Turkey and South Korea had spent the week in the town for the penultimate round and a series of school visits that saw them introduce their music and instruments to a host of local children. Three of these musicians made it to the final, which took place in a hall approached up a staircase flanked by suits of armour and a large Victorian collection of rifles. Known as the Waterloo Chamber, the room is hung with portraits of emperors, generals and clergymen who supposedly helped secure the British victory at the eponymous battle.

Sitting among them were the competition jury of five men and one woman, comprising French violinist Pierre Amoyal, German violist and former Berlin Philharmonic principal Wolfram Christ, British cellist David Strange, Windsor Festival director Martin Denny, Philharmonia Orchestra managing director Helen Sprott and Champs Hill Records executive producer Alexander Van Ingen.

First on stage was 22-year-old cellist Jonathan Swensen, a Danish student of Torleif Thedéen at the Norwegian Academy of Music in Oslo. He began with the third and fourth movements of Franck’s 1886 Violin Sonata, heard here in an arrangement by French cellist Jules Delsart. The sonority of the cello brings an extra dose of pathos to the music, something Swensen made the most of in a broad-bowed and searching account of the fantasia which showed off his ability to communicate with confidence and style.

This was earnest playing that still managed to retain a degree of subtlety. Particularly effective was the way that Swensen floated above harmonic changes in the piano, his sound without vibrato yet full of colour. By the start of the next movement, the intensity was perhaps beginning to sound a little overwrought and the higher, more lyrical passages were lacking ease and delicacy. A little roughness on the uppermost notes, however, gave the whole thing bite.

Much like the Franck that preceded it, Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata appeared to pose no technical difficulties for Swensen, who played its first movement next. His highly choreographed bowing brought to life the dancing curves of the theme’s dotted rhythms without sacrificing their essential Classicism.

Swensen floated above harmonic changes in the piano, his sound without vibrato yet full of colour

A reliance on swooping lines might have benefited from more clearly contrasting shapes elsewhere, though, and would have been supported by the piquant warmth that accompanist Nigel Hutchison drew from deep down in the piano. Last came the Capriccio from Ligeti’s Sonata for solo cello. Under different fingers such a hair-raising performance might have sounded rushed, but Swensen reached the finish line without losing either his breath or the clarity of line.

In the same way that Swensen’s naturalism was a great match for Ligeti’s vivid soundscape, British violinist Mathilde Milwidsky, 24, played with a honeyed tone ideally suited to Beethoven’s bittersweet ‘Spring’ Sonata in F major op.24. She performed the second, third and fourth movements, coaxing the short, halting phrases of the Adagio into long lines that alternated between silver and gold.

The ‘silver’ came courtesy of a sul ponticello that just occasionally acquired an undesirable touch of acidity; some string-crossings especially might have benefited from a warmer, fuller bow. Milwidsky navigated the whole of the slow movement with stylish empathy, and she sparkled in the scherzo and finale, where she made more of the opportunities for virtuosity than Swensen had done in the Franck.

She swaggered into Ravel’s Tzigane with a sourness that hung in the air, occasional interruptions from outsideno match for the heel of her bow. (Picturesque and imposing as its hilltop setting may be, Windsor Castle lies directly beneath the path of many aircraft taking off from nearby Heathrow Airport, the busiest in Europe.)

Trickier technical passages – like the octaves in the second half of the opening cadenza – didn’t always arrive in the dashing spirit in which they were written, but since this was also the case in simpler, folkish sections, the cause might well have been too much – rather than too little – focus on detail. Milwidsky’s left-hand pizzicato, however, was impressively taut and bright, and she seemed to lose some of her inhibition as the music gathered pace. Overall, this was an obviously well-prepared performance that could have done with having a little more fire breathed into it.

Last was 25-year-old Turkish cellist Jamal Aliyev, who began with an arrangement of ‘Méditation’ from Massenet’s Thaïs. Even the most familiar tune can be resuscitated by a skilled and soulful account; unfortunately, Aliyev’s was neither. Problems with intonation throughout did little to help elevate the performance to the level required. And then it was on to the first and fourth movements of Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata, where Aliyev’s big, warm lines helped address the balance, though tuning was problematic here too.

Aliyev is clearly capable of impressive subtlety, however, and brought a covered, mysterious quality to the composer’s harmonic twists and turns (accented further by the distant ringing of bells elsewhere in the castle). Tasteful phrasing and bow changes were further evidence that any shortcomings in technical preparation belied a clear artistic mind.

Though a little scrappy, Aliyev’s rendition of Paganini’s ‘Rossini’ Variations was flashy, highly musical and showed an instinctive awareness of the chamber dynamic. He alone of the three competitors could be seen communicating with the accompanist throughout, and there was an audible spontaneity to their playing that was not on display elsewhere. For the performance to have been truly convincing, however, Aliyev would have had to combine this innate musicianship with greater attention to detail.

Ultimately, though, the gamble appeared to pay off. Aliyev was placed second as well as taking home the audience prize (perhaps the Massenet had been a good choice after all). Milwidsky came third, which was a shame given her obvious diligence – though perhaps the result was a reminder of what makes some performances more exciting than others. Swensen, whose technical finesse – in contrast – had served to bring the audience closer to the music, was the well-deserved winner.

No comments yet