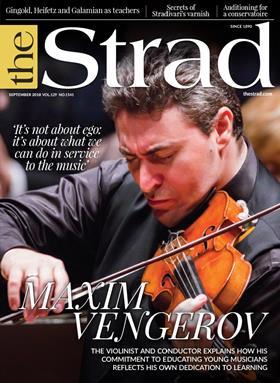

As one of the world’s most celebrated violinists, Maxim Vengerov has always been a dedicated educator. But, as he tells Charlotte Smith, his own education is a lifelong undertaking

This is an extract of a longer article in The Strad’s September 2018 issue. To read in full, download the magazine now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

At least three times during the interview, Vengerov repeats that ‘it is no longer good enough to be simply a good violinist’. It’s a lesson he learnt early on, when at the age of 16, following his sensational win at the Carl Flesch International Violin Competition in 1990, he abandoned his official violin education in search of wider understanding.

‘You’ll probably be surprised to learn that when I won the Carl Flesch, and I had around 70 engagements all around the world awaiting me, I still wasn’t sure that I should become a musician,’ he reveals.

‘Yes, I had won prizes for my interpretations of Beethoven, Brahms and Mozart, but music, as much as I loved it, was still a foreign language. I hadn’t discovered my own, distinct voice. So I decided to take my education into my own hands for a year. I took private lessons from top teachers in harmony, counterpoint and music history.’

Around this time Vengerov signed a contract with Teldec to record two albums, both released in 1992. The first included Paganini’s First Violin Concerto and Waxman’s Carmen Fantasy performed with the Israel Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta. The second was to be a recital disc of virtuoso works. However, the young violinist wanted to record a serious album of Brahms and Beethoven violin sonatas.

‘They thought that I, as a young kid, should be recording lighter works, but in the end I convinced the label head of my desire to become a good musician, not simply a virtuoso.’

This was a turning point for Vengerov and he readily admits that the four or five days spent in the studio recording that second album with pianist Alexander Markovich, listening intensively and critically to his own sound and phrasing, ‘was equal to two or three years of work’, and that he left the process ‘a different person’.

–

Mstislav Rostropovich, who conducted Vengerov in recordings of Prokofiev and Shostakovich violin concertos (1994, 1997), was a great mentor. ‘He was not only a brilliant cellist, but also a wonderful pianist and composer who worked personally with these great composers,’ Vengerov shares.

‘He raised the bar by one hundred times for me. My own students are all aware that my teaching encompasses the ideas of these eminent musicians and that no matter what achievement we make together, the goal is almost unreachable. But that doesn’t matter, as it’s not about ego: it’s about what we can do in the service of music, how we can be another beautiful branch of the tree, always connected to the roots.’

This is an extract of a longer article in The Strad’s September 2018 issue. To read in full, download the magazine now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

No comments yet