Guidance from The Strad 's archive on tuning, bow control, shifting, direction and pulse

Many students practise scales first, then arpeggios, and only after that double-stops, for which they often don’t allow enough time. In Elizabeth Gilels’ system double-stops immediately follow the scales, and only after that come arpeggios and chromatic scales. This helps to remind students to play double-stops and to allow time for it.

It is very important to play octaves, 10ths and fingered octaves every day, from as young an age as possible. They should all be practised in a slow tempo, then medium, and it is also important to play them fast, even though sometimes intonation suffers. As a rule, I recommend playing all scales without vibrato.

Boris Kuschnir, Teacher Talk, The Strad, 2011

This method of tuning scales was taught by Dorothy DeLay. Before playing complete scales, tune each note in the following order:

- Begin with the ‘skeleton’ of the scale, the notes of the perfect intervals: first, fourth, fifth and eighth;

- Then add the tow ‘leading’ notes: the third and seventh;

- Then add the second and sixth notes to give the complete scale, tuning both these notes in relation to the third and the seventh.

Simon Fischer, The Strad, September 2006

This is how I think you should practise scales:

- Start with two notes per bow very slowly, avoiding open strings as much as possible. Otherwise you will only remember first position and in a concerto or sonata we generally don’t use open strings.

- Play four notes per bow so that the bow is moving at the same speed as before but the left hand is going twice as quickly. Again avoid open strings. Play as many octaves as possible.

- Increase the speed to eight notes per bow with a slightly faster tempo, then 16 notes, and finally the whole scale in one bow. Use one bow up the scale and one bow descending. It helps to play really softly.

Jian Wang, The Strad, December 2005

Some musicians look at scales as warm-up material. This is a misjudgement. You should be properly warmed up even before starting to play them, in order to execute the stretched positions and double stops with a balanced left hand, and to play string-crossings with a bow that can respond to every type of contact with the string. The bow arm’s importance when practising scales should never be underestimated. Commitment with the bow gives the scale direction and pulse, shifting our attention to how it sounds and away from the area that is usually perceived as more difficult.

With the introduction of stretching, or extension, technique, the great cellist Pablo Casals created the illusion of a shorter fingerboard: he effectively made the instrument smaller. His new ideas helped minimise and in some instances eliminate shifts. Shifts that are not part of an interpretation, in the form of articulation or a beautiful glissando, must not be audible. This is especially apparent with scales.

Mats Lidström, The Strad, April 2012

A teacher who is convinced that scales practice is important will inspire their pupils to study them properly. You should tell students that a significant part of the Russian school is based on scales, and the results of that are not bad!

Easy scales can be used at first to develop an idea of what it means to play them ‘well’. Students should get some decent fingerings and learn them thoroughly. But my theory is that anyone who needs to read music to practise scales will have problems playing in tune by memory.

Bruno Giuranna, Teacher Talk, The Strad, 2011

Scales improve technique, but not just by paying them lip service. Simply playing through a couple of scales during a practice session will have very little impact on a pupil’s technical development. ‘Slim-o-Food will only help you lose weight as part of a calorie-controlled diet’, the ads tell us. Similarly, scales will only affect technique if they are part of a holistic approach to teaching. Time and concern must simultaneously be put into posture, arm positions, precision of finger movement and positioning. In addition, it is essential that the many connections with aural work are brought to the fore.

Paul Harris, The Strad, November 2001

These are the rules I follow: Play scales to the end of your life! Practise slowly. Don’t play loud and fast. Control your body. Think like a singer and feel the breath from your stomach. And finally, be patient and don’t give up.

Heinrich Schiff, The Strad, December 2004

Scale practice is as important for the right hand as for the left. The first thing is to achieve a beautiful detaché, whether you are using slow or fast bows. Play both as loudly and as quietly as possible in order to learn how to achieve the best bow speed and sounding point without sounding scratchy.

Practise scales and arpeggios for at least one hour every day, working on the right and left hands equally; then spend another hour on other technical elements such as double-stops (3rds, 4ths, 5ths, octaves), bowing, shifting and trills. After that, work on your repertoire – always a piece of Bach or Paganini alongside as many other works as you want.

Michael Frischenschlager, December 2015

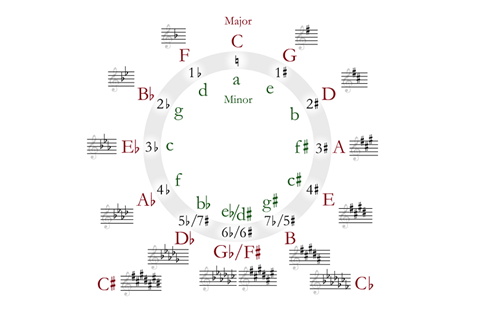

Instead of working through the circle of 5ths in your scales and arpeggios, try using random practice. Make little cards, each labelled with a different key, and put them in a bag. Then, make other cards labelled with different tempos and put those in a different bag. Finally, make cards specifying different bow strokes or bowings and put those in a third bag. Every day, pick out a key, a tempo, and a bow stroke and make this the subject of your day’s scale practice.

Molly Gebrian, September 2017

Using the method that I was passed down from my teachers, I like to start a four-octave scale in a slow tempo, one note per bow, four beats to a note. I do this both with and without vibrato. This allows me to practise my bow speed, distribution and control, and also to find comfort in my posture and left hand set up.

Then I move to two notes per bow, still in a very calm tempo. Then it is on to four notes to a bow, then eight, 16, and finally 32. Each step doubles the speed, moving from a lyrical scale to a virtuoso one. I like to do this in all keys, beginning with G major and up to C sharp major.

If I don’t have much time, once I have played the first scale in all variations, I will play the other ones at a fast tempo only.

Alexander Sitkovetsky, Blog, 21 February 2017

No comments yet