Brian Hodges and Diana Allan share their tips on coping with stage fright

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The following piece from our archive is linked to the Technique article in the March 2021 issue of The Strad on warming up the bow arm when playing the cello.

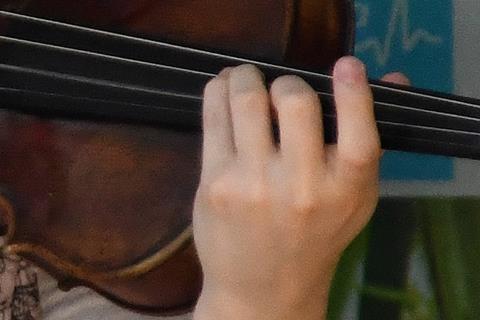

When we get nervous prior to a performance and go full tilt into fight or flight mode—our mind/body senses that we are in danger—blood rushes away from our extremities and to the vital organs and muscle groups that increase survival. Playing with ice-cold hands is no fun, especially if you’re trying to have a loose, wide, flexible vibrato.

The long-term remedy is to address the core beliefs that cause this reaction. The first step is to identify your specific doubts or fears. Ask yourself, 'What am I really afraid of?' or 'What am I worried about?' Many performers worry about making mistakes, of not playing perfectly, or not being good enough. Others fear what people (critics, audience, teacher, peers) will think of them or of disappointing or embarrassing themselves.

Once you have identified your fears, you can begin to challenge them. Let’s take the first one: making mistakes or playing perfectly. This belief can cause us to conclude that if I don’t play perfectly, then I am not very good. You can challenge this by recognising that 1) playing perfectly is impossible, 2) some of the most exciting performances you have heard are not perfect, but emotionally charged and musically interesting, and 3) that you have prepared to the best of your ability and can trust this preparation! By challenging your doubts and fears some fight or flight symptoms like cold or shaking hands, racing heart, or fuzzy thinking can begin to subside.

In the short-term, there are many effective strategies you can use to help you cope. I have worn gloves backstage before, and only taken them off just before I go out to perform. Some of my colleagues keep hand warmers in their cases to use before playing as well. During a performance, I have no problem blowing on them, or even sitting on them (during rests, of course!).

Read: Release the Fear Monster: how to conquer anxiety and perform at your best

Read: Conquering performance nerves: how do I control my fear of failure?

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Part of the problem is the lack of circulation getting to the fingers, so putting them down at rest by your side, even shaking them to get the blood moving can help. I have even resorted to doing pushups backstage to get blood going to my hands. It may seem extreme, but it really worked. Including a pretty extensive stretching routine as part of your warm up – perhaps incorporating some yoga or tai chi – will get blood flowing to the extremities where you need it.

During the performance, when you’re actively playing, it can help to make your gestures and movement even bigger. My tendency when my hands get cold is to shut down or make everything a bit smaller, perhaps as a way of conserving energy. However, opening up your playing, even exaggerating your movements, can have positive effects both physically and mentally.

Tip: To practise coping, try to recreate performing when you’re very cold. Crank up the AC or step outside briefly when it’s cold to simulate the sensation of playing while you’re cold. This gives you the opportunity to practise performing while using some of the strategies listed above. This type of practice—adversity practice—can increase confidence and better equip you for performing your best when it matters most.

Read our Technique article in the March issue of The Strad on warming up the bow arm when playing the cello.

Brian Hodges is an active soloist, chamber musician and teacher. He is associate professor of cello and coordinator of chamber music at Boise State University in Boise, Idaho. He is the principal cellist of the Boise Baroque Orchestra and performs regularly with Classical Revolution: Boise, which has been featured at the Idaho Shakespeare Festival and live on the radio at Radio Boise. He can be reached at www.brianhodgescello.com.

Dr Diana Allan is associate professor of voice at The University of Texas at San Antonio as well as a certified peak performance coach. She works one-on-one with musicians to help them assess both their strengths and challenges and teaches them how to cultivate the mental skills that will enable them to break through the barriers that prevent them from achieving optimal performance. Her website, Peak Performance for Musicians has a readership from 170 countries. Related topics

That festival feeling: Postcard from Odense

Davina Shum reports on the violin final of the Carl Nielsen International Competition in Denmark, an event that encourages a unique sense of collaboration and support between competitors

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

How can I help to conquer performance nerves by warming up my stiff, cold hands?

- 13

- 14

No comments yet