The German cellist on developing an intuitive understanding of music, and the importance of constant exploration

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

Read more premium content for subscribers here

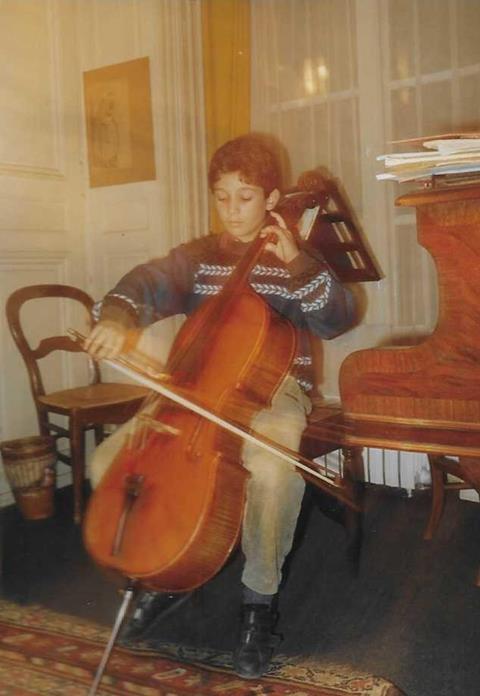

One of my early teachers, Michael Corssen, got me acquainted with period-instrument playing and recordings of Anner Bylsma, which shaped my ideal of how music – through the medium of the cello – should sound. I met Anner many years later and he still remains one of the most individual and witty artists I have encountered in my entire life. I also feel a huge sense of gratitude towards Marcio Carneiro, a larger-than-life personality who taught me every movement on the cello and how to create music with just an open string or a scale.

I met Eberhard Feltz through Quatuor Ébène, and he was highly influential. I remember him telling us a quote often attributed to Debussy: ‘L’émotion c’est la structure’ (‘Emotion is structure’). It made us students understand that you might only reach transcendence in music if you understand both the larger and smaller relations of all existing quantities. Nothing is random.

This was reflected in some of the exercises Feltz would give us students, such as taking the first four bars of a piece that we would then have to continue composing, or mixing up bars of a folk song that we would have to arrange in the right order. Sometimes he would give us eight alternatives of a Bach fugue, from which we had to find out the real one.

Exploring musical grammar with our intuition, and experimenting with the diction, pacing, direction and colours of every note brought us to a greater depth of what we experience as ‘emotion’. Sitting in lessons with him, as well as with György Kurtág and Ferenc Rados, were some of the most satisfying experiences of my life, as I was always left with the feeling of having gone as far as I could.

You can’t cheat time. It is the constant questioning and exploring that makes our life so beautiful. Witnessing Quatuor Ébène’s first violinist Pierre Colombet unpacking his violin and starting from scratch each day, after an unforgettable concert the night before, remains the biggest inspiration for me. I have learnt the most from musicians like him, and I like to surround myself with them, both on and off the stage.

Making music of any kind necessitates listening to your inner self. There is so much exterior noise in this world that can distract you from the peace and solitude with the core of life.

When you play the piano, you have the full score to yourself so you are never ‘alone’. Playing the piano is as important as playing chamber music, singing in an ensemble, reading a book, looking at a painting, learning your favourite poem by heart, going for a walk, taking notes. I envy Lied singers who live with an art form (poetry) inseparable from their music making. It should be the same for all musicians, so we can be in balance with ourselves.

INTERVIEW BY RITA FERNANDES

Read: ‘Like a fish in water’: Nicolas Altstaedt on Liza Lim’s Grawemeyer Award-winning cello concerto

Read: ‘It seemed like the Mount Everest of the repertoire’ - Nicolas Altstaedt on Dvořák’s ‘Dumky’ trio

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

Read more premium content for subscribers here

No comments yet