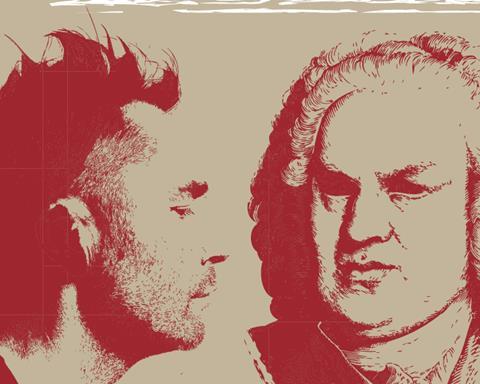

Nigel Kennedy used his recent BBC Prom to issue a condemnation of period performance. But, says Ariane Todes, he should get his facts right, and spare a thought for those colleagues whose reputations he's belittling

I love Nigel Kennedy, really, I do. I’ve been mesmerised by his Elgar, thrilled by his Vivaldi, convinced by his Bach and amused by his jazz. But he doesn’t half talk a load of rubbish sometimes.

In his programme notes for his solo Bach BBC Prom concert in August, Kennedy offered his view on the performance of Bach. He took a pop at the New York and Russian schools, but the real derision he saved for his authentic brethren. The main salvo: ‘Specialists are pushing Bach into a rarefied and effete ghetto which leaves many people feeling that Bach’s music is merely mathematical and technical – I see it as my job to try and keep Bach in the mainstream and present his music with, rather than without, its emotional core.’

The argument was blown up and shrunk down in the press, Kennedy got a lot of publicity from it, and I was going to let it lie, really, I was. He’s Nigel – he can say what he likes. But then I went to a performance of Bach that made me change my mind. The show was Bach’s St Matthew Passion performed with Baroque bows on modern instruments but in historically informed style by the Southbank Sinfonia at London’s National Theatre. As I listened to the subtly stylised phrasing, its inflections full of appropriately raw emotion, and the fruity timbres of the stringed instruments, I found myself arguing with Kennedy in my head.

Firstly, there’s no need to worry about marginalisation – Herr Bach can look after himself. He’s done pretty well in the face of such historically informed hooligans. The Olivier Theatre, which seats 1,200, was sold out over all four performances and the audience was ecstatic.

The Royal Albert Hall was sold out for Kennedy’s Bach Prom, too, and I was there. His Bach D minor Sonata was expressive and well-formed, exactly as he says it should be. But it was highly conservative. A week later, I saw Gil Shaham playing the same E major Preludio with which Kennedy started his concert. It had much more jazz and colour to it. So it’s a little ironic for Kennedy to criticise players who choose to play by certain formal rules when his conception of the music owes more to the type of research he rubbishes than he would care to admit.

There’s also a sour taste left by a musician who undermines the work of their colleagues publicly, and the danger that a whole genre gets sidelined. How would Kennedy feel about people losing their work through his comments? Players such as Giuliano Carmignola, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Fabio Biondi, Andrew Manze and others who have spent their lives understanding the origins of music don’t deserve that. Not to mention the leagues of players whose interpretations are informed and improved, if not necessarily determined, by academic research.

The necessary connection that Kennedy sees between authentic style and mathematical and technical playing that lacks an emotional core is misconception and prejudice. Music is either well played or not. He is right in his analysis that Bach must be played with attention to depth, architecture and emotion, but that goes for all music, and the fact that you understand the context in which a composer wrote doesn’t exclude you from realising that. Someone who has no knowledge of authenticity can play mathematically, too, so scorn that type of playing, yes, but not a whole approach to playing.

Ironically, Kennedy recently filmed a video for the BBC complaining about the eviction of a travelling community from a plot of land in Essex. One of his arguments was about diversity: ‘One of the things we’ve prided ourselves on in this country is the diversity of culture. For me, our culture is enriched by people who have got different ways of living.’ Doesn’t that go for interpretations of Bach, too?

Musicians have the right to express opinions, of course they do. This has been brought into sharp focus with the suspension of four players of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. That issue would take pages to pick apart and I wouldn’t want to wade in merely to generate an opinion without a considered analysis. And that’s exactly my point. With the right to free speech come responsibilities: the responsibility to be intellectually rigorous, logically consistent and properly informed; and the responsibility to be aware of any potential damage to your own communities. Without that, such proclamations are empty and provocative, and lead one to the conclusion that performers really should stick to what they’re good at – playing.

First published in The Strad, November 2011. Download the issue as part of our 30-day free trial, or subscribe to the magazine.

No comments yet