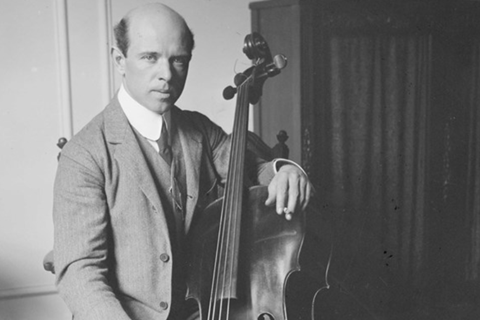

The legacy of Pablo Casals can be traced primarily to the methods of his colleague Diran Alexanian and favourite student Maurice Eisenberg. Oskar Falta explores the Catalonian cellist’s main vibrato theories, as communicated by these two associates

The following is an excerpt from the article ‘Pablo Casals: Boundless Expression’ published in The Strad March 2020 issue

Cello methodology always closely followed the more advanced methodology of the violin. When the innovative players of the Franco-Belgian violin school in the second half of the 19th century first introduced a practice described as ‘continuous vibrato’, the cello world still adhered to the old aesthetic of sporadic vibrato and had to wait for Casals finally to bring this innovation to cello playing. Casals, who represented the new direction, vibrated continuously and was capable of a large variety of vibratos. He would match the vibrato at all times to the character of the music instead of using it without premeditation. Many cellists vibrate consistently, without first considering where it is appropriate and whether their action reflects the intention of the composer. As Casals himself said: ‘Vibrato in itself cannot be expressive, because that depends on how it is applied. The vibrato is a means of expressing sensitivity, but it is not a proof of it’ (cited by David Blum in Casals and the Art of Interpretation, 1977).

On the other hand, Casals believed a constant vibrato might end up sounding monotonous and was not afraid of using open strings between vibrated notes, even in expressive melodies. He would avoid vibrato altogether in relevant situations, especially in softer dynamics or in moments in a duo when the cello is subordinate to the piano or plays an accompanying role. He emphasised that the piano is, after all, an instrument without vibrato.

- Watch: The great cellist Pablo Casals in conversation

- Read: Cellist Pablo Casals on expressive intonation

- Read: In focus: Pablo Casals’ 1733 Goffriller cello

On one occasion (as noted by Blum), Casals advised a student to practise a movement of Bach without vibrato for a whole week, in order to realise and appreciate the expressive capacity of the bow. This means that the vibrato must always work in complete harmony with the bow arm. Regarding this interdependence of hands, David Blum reports: ‘Casals’s vibrato was always receptive – but never superordinate – to the formulating activity of the bow.’

On the subject of the width and direction of vibrato, Casals found oscillation around both sides (flat and sharp) of the pitch disagreeable and preferred to vibrate solely towards the sharp side. However, this practice is one of the few Casals innovations that did not become an established norm: most string players today prefer to vibrate below the pitch (with the upper end of the oscillation falling on the pitch centre) or else around it – not exclusively above it. Even Bernard Greenhouse, himself a student of both Casals and Alexanian, taught vibrating below the note, which he expressed as vibrating ‘up to’ the pitch (Paul Katz, The Strad, July 2017).

To read the full article in which Oskar Falta explores the Catalonian cellist’s main vibrato theories, click here to log in or subscribe

The digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

No comments yet