Tim Duerinck reports on a research project investigating the possibilities of flax, carbon, aramid and more in violin making, while describing the surprisingly simple methods luthiers could use to create their own

The following is an extract of a longer article in The Strad’s July 2018 issue. To read further, download now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

Luthiers have always searched for the best possible material to make their instruments. The great violin makers we admire today did no less. From the materials available to them at the time, they found that spruce worked best for the top plate.

In the past few decades, countless new man-made materials have become available. The question is: if the great makers of the past had had access to the materials we have today, would they still have used spruce, or would they have opted for carbon, flax, a composite material, or perhaps combined two or more products in layers bonded together? Do any of these new man-made materials make it possible to produce violins with a specific desired sound? Can we make a violin sound louder, brighter or warmer, or give it whatever tone quality a musician might be looking for?

–

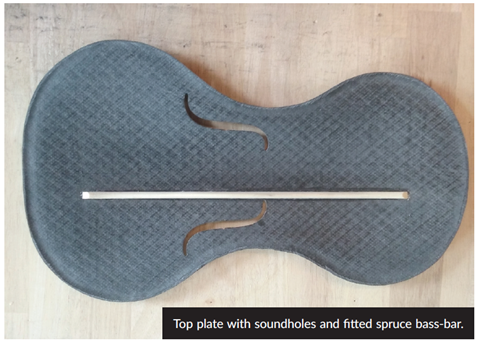

The focus of this research project is not engineering but musical instrument making. Can we extend the violin maker’s craft to include these new materials? To answer this question, we chose to make all the prototypes by hand, and without the aid of 3D software, the idea being that any luthier with standard training could use the making techniques we used, with a limited amount of extra training.

–

Scientific tests on these prototypes are ongoing and include double-blind listening and playing tests as well as more objective measurements, such as modal analysis. Spruce performs well, as is to be expected, yet it doesn’t seem to stand out as the overall winner among these prototypes. Some materials, such as a carbon-Nomex sandwich, seem better suited to creating a louder violin, whereas the flax violin appears to have a warmer, rounder sound. The two violins from woven carbon sound somewhat similar to me – but just like having two wooden violins, they don’t sound exactly the same!

What is a ‘perfect’ sound or a ‘better’ violin? If the answer is one that sounds like a Stradivari, we keep chasing our own tails as you can’t improve on something that’s already considered the best. However, if the answer is something more like ‘as loud or powerful as possible, with a rich and warm tonal colour’, then we have something to work with.

These initial prototypes represent the first steps in a very promising, but also very new, field of research. We have a long way to go to explore the possibilities these materials might offer, and make the most out of them. Violin makers have experimented with spruce for centuries, building on each other’s knowledge. Violins from new materials have a lot of development to catch up on, but in my opinion they show great potential.

Who knows what wonderful sounds are hidden in these new materials? Who knows what we’re missing out on?

The full article includes explanations of the key material properties density:speed of sound ratio, isotropy/anisotropy and damping, along with a description of the fabrication process with photographs.

To read it in full, download The Strad’s May 2018 issue on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

This research is supervised by: Ghent University – Research group Mechanics of Materials and Structures (UGent-MMS); Department of Art, Music and Theatre Studies (IPEM); and Hogent, School of Arts Gent, Department of Musical Instrument Making. It is funded by a PhD grant from the Research Foundation Flanders

Violin making and AI: Intelligent design

The science of violin acoustics has encompassed 3D scanning, CNC technology and good old-fashioned tap tones – so why not AI software? Sebastian Gonzalez presents the results of a project that could help predict an instrument’s tone qualities even before it’s made

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

New materials: Comparing violin tops made from various composites

- 8

No comments yet