In the January 2018 issue of The Strad, Rudolf Hopfner explores the CT scanning of stringed instruments, explaining how the technology works, some of the terms involved, and exactly what kind of revelations can be gleaned from the resulting images. Below, he interprets CT images of instruments by Amati, Stradivari, Stainer, Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ and Guadagnini to reveal the makers’ styles

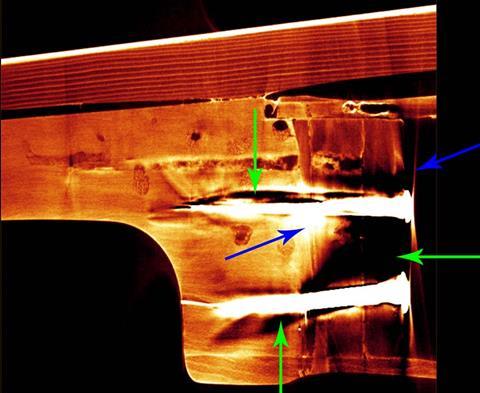

Micro-CT scanners use X-ray beams that are attenuated (reduced) on their way through an instrument. The attenuation factor of wood is relatively low; the one of glue is much higher; and the one for metals is higher still. So before scanning an instrument, it’s a good idea to remove all metal parts, such as overwound strings or tailpieces with fine tuners, prior to the scan. However, nails in original upper blocks or glues with certain metallic admixtures can cause havoc. This image shows the top-block of an Amati viola with two nails in place. In some areas, close to and especially between the two nails, image information is missing. With their high attenuation factor the nails erase the X-ray beams completely, which results in black spots (green arrows) and artefacts (blue arrows) in this area. It calls for the experience of the researcher to shift the window of the image graduation and other parameters to regain the little information that has been left.

To get an idea of how micro-CT scans can reveal instruments’ interior craftsmanship – and hence uncover the maker’s style – let us have a look at how some corner-blocks of old violins come out. When directly compared, differences in style and execution become clearly visible; true, these features can be inspected after removing the belly as well, but the micro-CT scan has the advantage that the data is available at all times, that we can provide visualisations of all areas of an instrument, and that a direct comparison of different makers is possible on demand. Here are example corner-blocks of violins by:

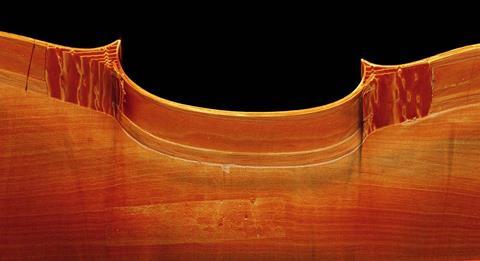

Jacob Stainer (Absam 1682):

Jacob Stainer used spruce for the corner-blocks and in this specimen the wood is strongly marked by hazel. Although we are looking at one of the last instruments of the master, the execution is remarkable and still shows a sure hand.

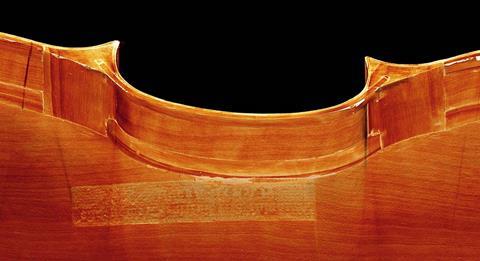

Antonio Stradivari (Cremona 1718):

Stradivari used willow for his blocks and linings, as can be seen in the difference of the structure of the wood. Note the two knife cuts in the lower corner-block. They are overshooting the mortise, a feature we often can find on Stradivari’s blocks.

Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ (Cremona 1731):

Guarneri’s linings are deeply embedded in the blocks. At some points the ribs display tiny cuts, which occurred when Guarneri cut back the lining with some speed.

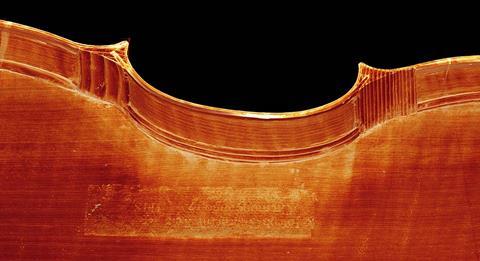

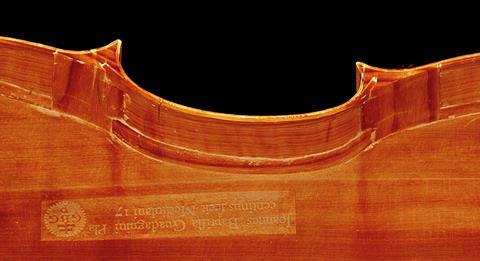

Giovanni Battista Guadagnini (Milan 1751):

Guadagnini’s work shows similarities with Stradivari, however on a slightly lower level of execution. The lining in the lower corner has been inserted with force, thereby splitting the block. Guadagnini’s label shows another detail worth mentioning. In this rendering the printing ink is clearly visible, as are to a lesser degree the ones on the Stradivari and Guarneri labels. With further research and an even bigger sample of scanned instruments, one day it could be possible to make statements about the authenticity of labels as well.

Images and video courtesy Violinforensic

No comments yet