Once upon a time, violinists just wanted to get as close to Heifetz's sound as they possibly could. But now that golden standard no longer applies, Jessica Duchen asks, how do the stars of today mark themselves out as special?

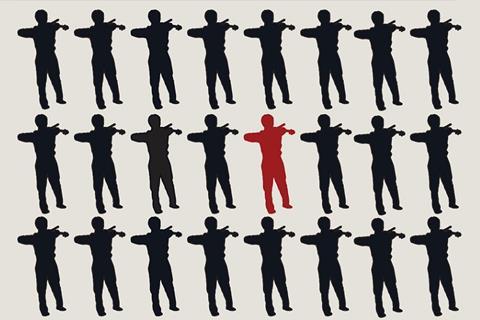

Over the years I’ve interviewed more violinists than I’d care to count. What do they have in common? Maybe it’s paradoxical, but the one issue that comes up time and again is the question of individuality in sound. It can be a preoccupation, even an obsession: exactly what gives a violinist a singular, identifiable tone remains one of the great mysteries of the musical world.

This isn’t confined to violinists: it applies to any instrumentalist, including pianists. And conductors, for that matter. But when I first worked for The Strad at the end of the 1980s, it was the violinists who went on about it: ‘Of course, my idol is Heifetz, but nobody today has any individuality.’

I started wondering if that might be no coincidence. After all, if so many violinists were saying the same thing, worshipping Heifetz and navel-gazing over why they didn’t sound as ‘individual’ as he did, was that perhaps why they had all begun to sound the same?

It’s not that simple, of course. Plenty of other factors were taking their toll on the profession: the dominance of certain sought-after teachers, the pressure from recordings to attain impersonal ‘perfection’, and so on. And the truism remains that no other violinist has ever sounded like Heifetz, nor ever can.

Nevertheless, I haven’t heard that little phrase about Heifetz-worship for a while. The string world has changed with time: today recordings are more likely to be live, some teachers are no longer with us, and Heifetz’s memory is beloved but maybe no longer quite so dominant. The increased availability of historical recordings has helped to alert younger players to great artists as different as David Oistrakh, Jacques Thibaud, Joseph Szigeti and, naturally, Fritz Kreisler.

The rise of interest in period-style playing has increased the range of reference points open to developing musicians. Many in their 20s or 30s can switch styles with ease – Alina Ibragimova is one example – or can simply take what they like from each approach and apply it at will. And the idea that individuality is self-evidently a good thing has embedded itself in string players’ consciousness to a much greater degree.

It’s the violinists who know they already have their own tone who seem least likely to obsess about it. Pinchas Zukerman is a case in point, suggesting to me in an interview a few years ago that a violinist is born with a personal sound, as individual as a fingerprint – it can be developed and perfected, but not essentially changed.

Read: Technique: Developing bow control for improved tone

Read: Technique: Creating sound from the imagination

Read: How to produce a strong, uninhibited sound without pressure, by cellist Joel Krosnick

The components of personal sound are difficult, if not impossible, to separate from issues of personal style. Anne-Sophie Mutter’s sound may not be instantly recognisable, yet her style, with her fondness for extremities and micro-expression (which divides listeners) could belong to her alone. Pekka Kuusisto is another radical, bringing notions from folk playing and Baroque style to bear on all manner of different repertoire. Sometimes it’s convincing, sometimes less so, but he is usually willing to take the risk.

Speed of vibrato has a role, along with weight of the bowing arm, rapidity of attack and so on – but there’s a more elusive factor. Renaud Capuçon’s playing is distinctive for its mingling of intensity and amplitude with a suave feel for colour. Leonidas Kavakos could scarcely be more different: slimmed down but very focused and startlingly bright within self-imposed constraints, rather like an Olympic runner. There’s the super-refined yet incisive sheen of Nikolaj Znaider and the rich, generous warmth of Gil Shaham. And even if many of those violinists are well under 50, Zukerman’s swashbuckling strength and depth of tone is pretty much unmistakable.

The best instrumentalists play as the people they are: their personalities infuse every facet of their performances. And it’s true of pianists too. I remember coming home from an interview with Mitsuko Uchida and switching on the radio to hear her playing a concerto. The piano ‘voice’ that shone through was exactly the same as the human voice that had been talking to me an hour earlier.

How does it happen? The mystery lingers. But what seems clear is that string players are embracing their individuality more happily today and nurturing the distinctiveness of their own personal sound. Long may that continue.

Read: Must all orchestral string sections sound the same?

Read: 10 tips on maximising tone quality & projection

Read: Aaron Rosand on how to produce a beautiful tone

Explore more Technique articles like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet