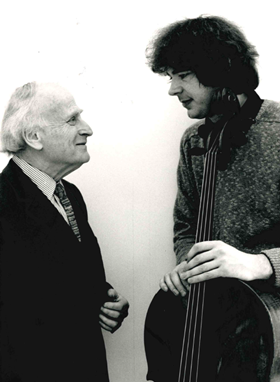

The British cellist and now conservatoire principal talks about the challenges facing music education, and his adventures in finding new repertoire

This article is from the July 2018 issue of The Strad

One of the things that first fascinated me about the cello was the repertoire. When I was around 13 I saw Rostropovich play more than 30 concertos across 9 concerts in London, and although I remember being mildly annoyed even then that he left out the Walton and the Delius, it really opened my eyes to the variety of music written for the instrument.

Much of it had only just been recorded, and sometimes the Radio Times listings for an obscure foreign station would include a piece I didn’t know, so I’d record the broadcast on reel-to-reel tapes. When I was a student at the Royal College of Music in London, it was a huge adventure to go through the archives of the nearby Institute of Recorded Sound to find music I’d never heard before.

Maybe it’s precisely because so much music is so easily available today that students don’t always bother to look for it, and come to lessons with the same pieces by Dvořák, Elgar and Bach. People are becoming less curious, not more – I’d like to see students use everything that’s available to them in a much more creative way.

What hope do we have of shedding the ‘elitist’ tag if only those with rich parents get to learn an instrument at school?

I don’t know what I would have done when I had to stop playing had I not already been involved in music education. It’s an extreme example, perhaps, but you need to be aware of the world beyond your instrument and to keep your mind open to the full range of opportunities available. Many of the most successful people in music I have worked with over the years have been recording engineers, producers or arts centre directors – not things they thought they would end up doing when they first arrived at music college.

Being a well-rounded musician and taking an interest in the whole subject is more important now than it ever has been before. The days of shutting yourself away in a practice room and never looking up from the music stand are over.

We as musicians have a duty to introduce music to children who have been deprived of it by government cuts. We can’t do it on our own, though, and if society continues down the road we are on, there will be very bad consequences for classical music.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason’s first cello lessons were at the state school he attended in Nottingham – the same school that is now planning to remove instrumental teaching from its curriculum. What hope do we have of shedding the ‘elitist’ tag if only those with rich parents get to learn an instrument at school? What chance does someone have of entering the profession if their first contact with classical music comes after they’ve already left school?

Becoming a teacher is no longer thought of as second best to a performing career. The example of El Sistema in Venezuela has shown how music education can be a powerful engine for social change; part of my work as principal of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire has been to establish a programme of outreach work to bring music to schools that would have little access to it otherwise.

Some of our students were a little reluctant to get involved at first but now we have a waiting list of almost 200. Having a good teacher is vital, and can awaken something you didn’t know was there before.

Julian Lloyd Webber is Principal of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire and chair of Sistema England

INTERVIEW BY TOM STEWART

1 Readers' comment