The acclaimed solo and chamber bassist stresses the importance of self-reliance and self-discipline in building a meaningful career and life

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

Still to this day, I ask myself ‘what would Zoltan say?’ Zoltan Kovats, the Hungarian double bassist and Cape Town Symphony Orchestra principal I called my teacher for a year, has had a lasting impact on me. There was no compromise in his style of teaching. If you didn’t practise, you would be kicked out of the class. It became obvious to me early on that self-discipline was essential in building a worthwhile musical career. This was accompanied by my father’s perfectionism – he would be the type to ask where the missing five per cent went when I had achieved 95!

Due to Zoltan’s contacts, I played in Cape Town’s Symphony Orchestra from a young age, instilling in me a strong professional ethic. While I was still learning cello with Edna Elphick, a student of Pablo Casals, I also received wonderful opportunities, such as playing for Pierre Fournier. But perhaps most importantly, Edna made me understand music’s ability to touch others very deeply. Music is not a fashion accessory; it is a way of life. It is important to always aim for something bigger and be humble enough to seek advice.

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #21: Leon Bosch on Bottesini

Read: ‘He is a similar weirdo, in the good sense!’ - Rick Stotijn: Stepping into the spotlight

I was the wrong colour in music and had to disprove prejudices every day. This taught me to never rely on others in life, as this would lead to disappointment. If I wanted a new instrument, I would have to find the money myself. And when I wanted to move to the UK, I had to find the means on my own. Others will simply not fund your dream, as it is not theirs. Self-reliance and self-discipline are the two most important ingredients in any life of value, regardless of whether one is a musician. The injustices I faced early on as a political prisoner in South Africa also influenced my choice of instrument. The double bass is the underdog, and I quickly found an opportunity to be an advocate for it. I learnt the double bass in a way that would liberate it from its stereotypes.

Important management decisions in classical music are currently being made by people ill qualified for the job and with no intrinsic experience of music. The wealth of knowledge is held by the musicians themselves, and yet they subordinate themselves to things they are simply not paid enough to do. I have seen this first-hand, with pieces being commissioned that the musicians do not like, fostering a hostile and discouraging environment. When musicians collaborate, beautiful things can happen. My experience playing Dvořák’s Quintet no.2 with the Lindsay Quartet, for example, demonstrates this. Their collective ability to take extraordinary risks made for a truly transcendental experience – so much so that I could barely sleep when I got home! Sovereignty should be returned to musicians, where it rightly belongs, so they can create their own projects, playing repertoire they love and building a more collaborative future for classical music.

Interview by Rita Fernandes

Read: Sentimental work: Rick Stotijn on Joseph Marx’s Adagio

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

-

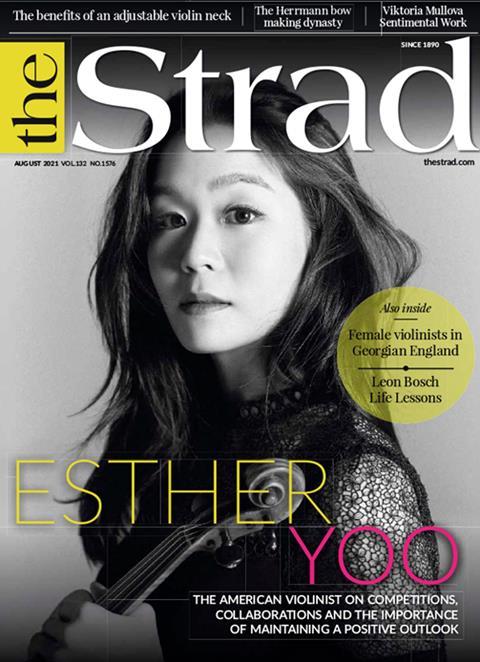

This article was published in the August 2021 Esther Yoo issue

The American violinist on competitions, collaborations and the importance of maintaining a positive outlook. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- American violinist Esther Yoo

- The benefits of an adjustable violin neck

- Bach’s Solo Violin Partitas

- The Herrmann bow making dynasty

- Female violinists in 18th-century England

- Making accurate arching templates

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet