The Israeli violinist talks about dealing with self-doubt and developing a strong work ethic

When I think of my first teacher in Riga, Romans Šnē, I have memories of an incredibly patient man who suffered through teaching this impossible kid who couldn’t sit quietly for two minutes. He taught me that certain things are expected, whether you like it or not. It might be a cliché, but he really made me fall in love with the violin. After eight years with him, I moved to Novosibirsk to study with Zakhar Bron. It was incredibly enriching to be around such talented musicians. We would attend each other’s lessons and practice sessions, and still today when I meet with classmates we can’t stop talking about that time. That one year there gave me a real kick-start.

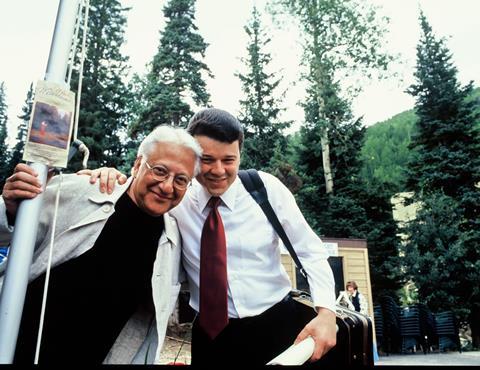

Only two weeks after arriving with my family in Israel at 16 I heard that Isaac Stern was going to listen to young violinists at the Jerusalem Music Centre. By sheer luck I bumped into him at reception and asked to play for him. Out of pity, he agreed to listen to me for five minutes – which turned into two hours. I left that room with a clear understanding that I knew absolutely nothing about music and violin playing. If it was not for that afternoon in 1990, I wouldn’t be the musician I am today. He insisted I started playing second violin in Haydn quartets. For a young, cocky Soviet violinist, that felt like such a downgrade! But my saving grace was that I was stubborn and curious. Once I caught the virus of chamber music, I never went back. Stern also made crystal-clear something I had got from my first teacher: that nothing was ever good enough. It instils in you a perpetuum mobile that simply refuses to stop. It is an indispensable quality in an artist, and without it, we can happily – or not happily – retire.

Looking back, I’d listen more to my inner voice

At a festival in Dallas at the age of 18, I played for violinist Arkady Fomin. I still remember working on the Bach G minor Adagio for three hours. I quickly decided that I had to do everything possible so that I could study with him. It was one of those star-aligning moments, where I found the teacher to get me out a period of serious self-doubt. He became family, a friend and confidant, and took me from almost quitting to launching my career. His biggest power was a contagious belief in his students. He left me no choice but to believe in myself.

Looking back, I would tell myself to listen more to my inner voice. The times when I did this were life-changing. My biggest obstacle was always myself. In the end, you are the one responsible for pulling through, and it depends on how much music means to you. I remember going to Dorothy DeLay when I was at Juilliard, complaining that I was tired and stressed. She replied, ‘Sugarplum, if you think it’s too difficult, go work in a bank. You can go back home and forget about work.’ We don’t make music; we live it. You do it because you need to do it. Then any obstacle is solvable.

INTERVIEW BY RITA FERNANDES

-

This article was published in the June 2022 Pavel Haas Quartet issue.

The Pavel Haas Quartet gives a lively account of their first two decades together, and their upcoming Brahms recording, in conversation with Tom Stewart. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet