Rok Klopčič takes a look at different types of vibrato through the eyes of the great teachers and players - from the June 2003 issue

There is hardly a facet of string technique in which technical and artistic factors are so closely intertwined as in the production of vibrato. While being a form of expression that is often used unconsciously, it is also a tool that must be carefully understood and mastered.

Mechanics

In former times, players such as Flesch and Rivarde thought that the variation of the pitch should move both under and above the note. Now, however, it is generally accepted that vibrato should be what Ricci describes as a 'flatting'. Likewise, Spalding asserts that 'a beautiful vibrato is the one that sounds the note and lowers it.'

There are three discernible types of vibrato, named according to the part of the body that performs it: arm, hand (otherwise known as wrist) and finger vibrato, although for Szeryng, 'a perfect vibrato [is] a combination of finger, wrist and forearm.'

Galamian would agree with this, claiming that between the three categories there lie about a hundred types of vibrato which are the results of combinations of the elementary types as well as variations in amplitude and frequency. This variation is fundamental as Ricci explains: 'The width and speed of the vibrato are extremely important: in the upper positions faster and narrower; in lower positions, wider and slower.'

History and aesthetics

The transformation in the use and the quality of vibrato started with Ysaÿe at the end of the 19th century and by the first half of the 20th century, vibrato technique eclipsed all that had come before it. According to Henry Roth, Kreisler was the first renowned violinist to employ the constant use of vibrato. Flesch described his vibrato as 'extraordinarily intensive' and Elman as giving his playing a 'real glow'.

This development was not welcomed by everyone. As late as 1921 Auer wrote: 'This curious habit of vibrating on each and every tone amounts to a physical defect, whose existence those who are cursed with it do not in most cases even suspect.'

These days the ideal is generally a continuous vibrato with many colours which are the result of mixing different types of vibrato at different amplitudes and frequencies. The choice is made intentionally or subconsciously; for Stern it was important that 'the vibrato should be very carefully planned.' This choice shows each violinist's idea about the character and style of the music performed and, perhaps even more, the player's own musical personality. After all has been practised, said and written, there is some truth in the words of Heifetz: 'Vibrato... is part of each individual musical personality, something one is born with…expressing one's temperament.'

'This curious habit of vibrating on each and every tone amounts to a physical defect, whose existence those who are cursed with it do not in most cases even suspect.' - Auer

Teaching

There will be little disagreement with Szende's claim that 'basic movements of the vibrato can and must be studied in the same manner as the other movements in violin playing.' Appropriate exercises provide the basis for every serious approach to vibrato.

The question of when to start teaching vibrato to young students has received many different answers, but it seems that pedagogues now agree with Ilona Feher, who thought that 'vibrato can be taught... and it should be developed at an early age.'

Seling believed that vibrato can be taught in the first year of playing, in first position or when the student has learnt third position. For Persinger, 'as soon as a pupil expresses a desire to learn and use the vibrato, the teacher should explain the process of its development in detail. The study should begin not later than the first efforts towards learning the third position.'

Exercises

The following exercises should be practised in appropriate doses through the whole of a violinist or viola player's professional life to delay the onset of what Flesch called 'the violinist's arteriosclerosis, the atrophy of vibrato'. As Francescatti warned, 'vibrato is one of the first of the technical elements to deteriorate.'

Wrist vibrato

When developing vibrato, start in third position, moving on to the others later. The lower part of the left hand starts off in contact with the instrument. The hand drops backward from the wrist and returns forward to its starting position. The finger submits to the motion and describes a rocking motion on the string. Galamian insists that it must not lose its place on the string and suggests the following exercise.

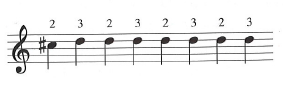

Notes with stems pointing down indicate the flattening of the pitch.

Arm vibrato

The same principles apply as for hand vibrato: the finger should be firm enough to retain its place on the string, but flexible enough to submit to the impulse which here comes from the forearm. This exercise should start in first or third position:

In both these exercises use a metronome to gradually increase the tempo, so that first two, then three, then four notes are played to a beat.

Finger vibrato

To get the fingers used to the motion described in finger vibrato, in this Flesch exercise, the finger should be placed as if playing a harmonic note and then should press the real note, continuing to alternate between the two:

It is also important to loosen the finger joints. Galamian offers an exercise for exchanging fingers on the same note:

Galamian also suggests stretching and bending the joint nearest the nail by sliding the finger forwards and backwards on the string.

To loosen the fingers and the hand, Rodolfo Lipizer suggests keeping the thumb in first position, and playing glissando with one finger the distance of a sixth. Then lessen the distance to a fifth, fourth and so on down to a semitone. This should be tried with different fingers and in different rhythmical patterns.

Ricci developed the next exercise for finger vibrato: 'The rolling motion generates from the lowest knuckle on the finger. It is produced by bending this knuckle in and out. There is no arm motion; just fingers and wrist.’ Using double-stops supports the joints.

Continuous vibrato

Continuous vibrato can be practised by playing different intervals using each of the different vibratos, making sure that the sound while changing fingers is uninterrupted and regular:

It is also important in all the different types of vibrato, to experiment with factors such as speed and finger placement. Samuel Applebaum observed in the vibrato of Heifetz that 'improvement may be obtained by the slight change of finger angle for different speeds'.

Read: 10 things you need to know about vibrato

Read: Leila Schayegh's top 5 tips on historically informed vibrato

Read: Why can't players get vibrato right?

Explore more Technique articles like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Violinist Lihay Bendayan: Fourth finger vibrato

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently reading

Currently readingDeveloping arm, wrist and finger vibrato

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

No comments yet