Roger Tapping, violist of the Juilliard Quartet, on the faculty of the Juilliard School, and formerly New England Conservatory, gives a lesson on improving vibrato, particularly for violists

Vibrato is a wonderful, expressive tool that can add life, emotion, sensuality, inflection and so much more to our sound. It requires a deep connection between both hands, which unite to serve our creativity. This has as much to do with listening critically as with technique. Using our imaginations can guide us more effectively than thinking abstractly about vibrato speed and width. This article is for those who find that, as they play louder, their vibrato sounds tight and stiff, preventing the sound from blooming and singing, and for those whose vibrato is too wide and rich, like thick polish that hides the grain of a fine wood.

For a warm vibrato, viola players, more than violinists, need to play on their finger pads and less on their tips: viola strings are longer, so more of the finger is needed to make the same pitch variation. Lean your left hand back a little towards the scroll so that your fingers point down along the fingerboard without losing some curve of the knuckle; feel for the soft part of the finger pad. This allows more room to vary the vibrato width depending on the expressive needs of the music. On the other hand, you can play much more on your fingertips for precision in swifter passages.

CRESCENDO AND DIMINUENDO EXERCISE

The more sound one makes with the bow, the wider the vibrato must be to maintain the same warming and enlivening effect. This exercise will help you to develop that connection. If you get stuck, go to the ‘wobbly exercise’ described on the opposite page, then come back and try again.

- Choose a note to play with your second or third finger in third position on the D or A string.

- Play very softly with a lovely shimmering sound and with free bowing, and listen to how small a width of vibrato you need to make your sound alive and alluring to the ear.

- From now on, crescendo very gradually, still bowing freely. As you begin to play more fully, always imagine what your sound might be expressing – perhaps an alto or soprano singing Mozart intimately and sweetly, with beauty and hope. Does your vibrato continue to warm and enliven your ‘voice’ as your volume increases?

- Allow your knuckles to be flexible.

- Lean your finger pads back into the fingerboard as your bow falls more deeply into the string. When you’ve reached your top volume, think of a full-voiced singer with passion and depth in her voice, and imagine what she is singing about.

- Now reverse the process, descending gradually back to the beautiful soft sound you began with, always envisioning specific emotions and voices.

- If you’re listening very acutely and always making a sound you love, your vibrato will naturally become less wide as you diminuendo.

- Repeat the exercise on different notes and strings, and in different positions, from the bottom D flat on the C string to high on the A string. Listen for how different vibrato speeds suggest different feelings and emotions.

Let your ears guide you to coordinate your left and right hands. If your vibrato grows independently of the sound you make with the bow, it will become unfocused and wobbly; if your bow sound grows faster than the vibrato width, the sound may become edgier or plainer than you would like. With careful imaginative listening, your hands should naturally develop an instinct to work together. In fact, imagining a particular sound in your left hand will instinctively affect how you use your bow.

Now surprise yourself by changing dynamics, sounds and moods. Ideally, both hands will change together as your imagination takes you through the gamut of emotions. Use your taste and creativity throughout. If you think you sound thin and tight, or wobbly and unfocused, you probably do.

THE ‘WOBBLY’ EXERCISE

If your vibrato is too stiff and narrow, try this warm-up:

- Choose an easy note to play with your third finger.

- With your left hand, wrist and arm loose and relaxed, pretend you’re playing a modern piece where you need a grotesque, exaggerated vibrato, marked with big, wavy lines. Pretend you are an ‘over-ripe’ opera singer, singing with very little pitch centre, but don’t actually leave the note.

- Play loudly, without discipline in the left hand. Relax your knees and face; be loose and lazy in all your limbs and joints.

- Don’t worry about consistency. Even if you normally have a very stiff vibrato you will be able to do this. Being horribly loose may be a revelation to you! Gradually rein in the vibrato to taste. Try this on each of your fingers, always making a resonant sound with the bow.

VIBRATING ON DIFFERENT FINGERS

Each finger feels different: the first is bonier and less willing to be on its pad. Because of its frequent role in shifting or reaching back, pay particular attention to its angle to avoid its default fingertip position. The fourth finger is thinner, shorter and lighter; one way to compensate for its weakness, which often results in a tight and tentative sound, is to bring the arm around as you would when playing in a high position. This will enable it to lie on its pad, almost perpendicular to the fingerboard. From here, the motion of the arm rolls the finger from side to side, making more pad width available. In expressive playing, let the knuckle invert itself to allow the finger to sink into the string. To find this feeling:

- Sit down and put down your bow and rest the viola on your knees, in cello position. Place your left hand and arm so that the fourth finger is in a straight line perdendicular to the fingerboard, resting on one of the middle strings.

- Move the arm and finger up and down the fingerboard, then gradually reduce the motion until the fourth finger rests on one pitch. Continue the arm motion, rolling the finger over its tip.

- Try to reproduce this motion in a normal playing position.

Another trick is to drop the fourth finger swiftly from higher up than you are used to, to compensate for its lighter weight and to prevent tentativeness. Let it fall heavily and ‘hit the ground running’, vibrating as it sinks into the string.

PASSING VIBRATO BETWEEN FINGERS

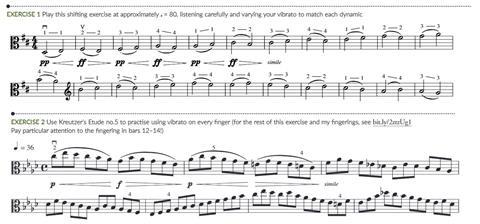

In exercise 1, from my teacher Bruno Giuranna, add the indicated dynamics with the same imaginative vibrato-listening as before, to grow the sound from a delicate pianissimo to a warm, passionate fortissimo and back. As you play each of the crescendoing notes, listen to whether the following finger gives a satisfyingly rich peak. Use all the available resources of the bow to vary your dynamic: contact point, weight, and especially distribution. Save bow while in pianissimo so you can make a crescendo by increasing bow speed as well as weight.

Having mastered the exercise in 2nds, try shifts of 3rds, then 4ths, 5ths, 6ths, 7ths and octaves, all in D major (so not all 4ths and 5ths, for example, will be perfect intervals). Always listen for how your vibrato helps you to mould the dynamics, and return to the minimum you need to make a magical pianissimobefore loosening up to find the beautiful full peaks.

Kreutzer no.5 (exercise 2) is another way to practise passing vibrato from one finger to another. For some players, good training in finding a secure hand frame can make them reluctant to get off their fingertips. In constantly varying the amount of finger pad as one passes from fluttery to rich vibrato and back, the angles of the fingers will naturally vary with imagination of colour. This continuously subtle variation breaks up a rigid form which so often leads to fatigue and stiffness.

Having expressively mastered Kreutzer no.5 in first position:

- Transpose it into higher positions: in second, begin on D natural; in third, E natural; in fourth, F sharp; in fifth, G natural.

- As before, vary bow weight, speed, distribution and contact point to move from piano to forte and back.

- Listen for how your vibrato grows through the crescendos to a rich forte no matter which finger you use, and reduces with each diminuendo.

- Think ahead to prepare forte fourth fingers, and make sure the first finger is ready to land on its pad when it is at a rich peak.

- Listen for whether you are continuing to make the whole viola ring fully as you transpose to the higher positions.

REPERTOIRE

Shaping musical phrases means rising and falling subtly in dynamic with the harmonic and melodic contours of each phrase. In the opening of Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata (example 1), listen for how vibrato helps the small melodic peaks and valleys. Notice how the melody gradually climbs in register, and let your vibrato reflect this, to help the top notes shine.

There are many beautiful ways to play the Courante of Bach’s D minor Cello Suite (example 2), but for now, use it to practise speeding up a slow vibrato. Play it first with a metronome at a quarter note = c.42, with an impulse vibrato on each bow stroke. This is most effective when played detaché with small, varying impulses on each stroke – not totally legato – to match the left-hand impulses. Use your imagination and sense of harmony to shape the line and make it vivid and colourful, despite the slow speed – think of a soprano, alto, tenor or baritone. Your bow strokes will naturally vary in length and weight. When you’ve really mastered this, build up the speed a couple of metronome clicks at a time. As you get faster, your vibrato will gradually become livelier. Continue to listen for how it can colour the notes you find most significant. I am not advocating this as an ideal way to play the Bach in terms of style, but it’s a nice way to develop coordination of left hand and right arm.

–

Kreutzer no.5 (pictured below) is one way to practise passing vibrato from one finger to another. For some players, good training in finding a secure hand frame can make them reluctant to get off their fingertips. In constantly varying the amount of finger pad as one passes from fluttery to rich vibrato and back, the angles of the fingers will naturally vary with imagination of colour. This continuously subtle variation breaks up a rigid form which so often leads to fatigue and stiffness.

IN YOUR PRACTICE

There is no hurry – practise the exercises in this article over a period of days or weeks and in sequence; don’t move on until you are happy with the previous one. Use your own taste throughout – trust your judgement.

TIPS FOR TEACHERS

Keep students on an imaginative plane to help technical instincts develop naturally. Most respond well to words that suggest colours, moods and voices. The less abstract the better.

INTERVIEW BY PAULINE HARDING

Listen to how expressively Menuhin varies his vibrato in the passage from 2’38” to 7’35”

Violinist Lihay Bendayan: Fourth finger vibrato

In this extract from the March 2022 issue, violinist Lihay Bendayan provides tips on how to improve a weak fourth finger vibrato

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Technique: Viola vibrato, and how flexible joints and a keen ear can enhance your expressive range

- 11

- 12

No comments yet