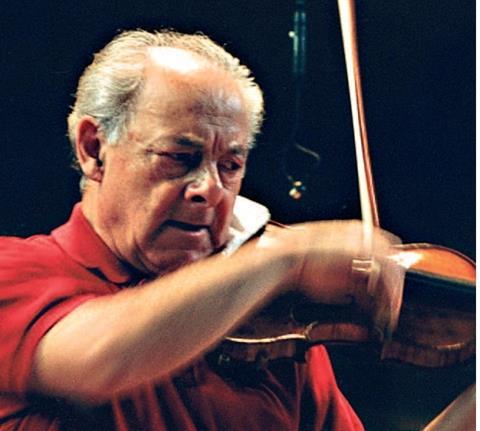

The leading soloist and Royal Academy of Music professor celebrates 80 years of violin playing in his new autobiography

When I left communist Hungary at the age of around 21 my life changed. I was one of the first students allowed to travel to the West: in 1955 I had a student quartet and we were allowed to go to Belgium; the next year I was allowed to travel to Italy, and I couldn’t believe the way the people lived and talked to each other so openly. That was when I decided I had to leave Hungary permanently. I couldn’t live in a prison any more, and I realised this was the only way to free myself.

This isn’t to say there weren’t wonderful string teachers in Hungary. We were all in a prison together and there was nothing else to do but practise. I liked opera and was at the opera house often, but we had nothing else – no television, no shows, just studying and practising. We were cut off entirely from Western European culture. We weren’t even aware of how far contemporary music had progressed – we had Khachaturian, Kabalevsky and some Shostakovich, but no Stravinsky.

In 1956 I had some concerts in Paris and decided I wouldn’t go back to Hungary. I grew up without parents, as they had died in the Holocaust, but I had one grandmother and was afraid to leave her there – but in the end I didn’t return for 17 years. In those days you worried about returning to your country and not being allowed to leave again, but by the time I visited Hungary again I had been a British subject for many years and had a big name. I shouldn’t have been afraid, but I was.

I spent some time in Paris and then Holland, but eventually Yehudi Menuhin, who I had first met in Hungary, persuaded me to come to the UK. He wrote a letter of recommendation to the Home Office to say I would be a student of his. At first, I was given permission to come for three months and in time I was able to stay permanently.

That time in London was a golden age for classical music. All the famous names, like Daniel Barenboim and Radu Lupu, wanted to be there. In the 1960s and 70s I performed non-stop concerts. I had won three international competitions (the 1956 Paganini Competition, the 1956 Munich Sonata Competition and the 1959 Marguerite Long–Jacques Thibaud Competition) and in those days, competitions meant much more than they do now. When you won first prize in a big competition you were invited to give many concerts.

I spent my life in hotels and on aeroplanes, making recordings and performing for hundreds of local music societies, for the BBC, in churches and so on. I had important and long-lasting relationships as a soloist with three main orchestras – the London Philharmonic with which I recorded the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto; the London Symphony Orchestra, which offered me the concertmaster’s chair initially, but which I turned down; and the London Mozart Players.

Read: Violinist György Pauk on studying with Ede Zathureczky and Leó Weiner

Read: ‘Young players today should be realistic about making a career’ - violinist Pinchas Zukerman

Nowadays the biggest issue for my students is getting concerts – and this was an issue even before the pandemic. Music isn’t thought to be as important as it used to be by the general public. Or perhaps there’s too much of it, or too many young players of a very high standard. I have top students from all over the world, many of whom take up important positions leading orchestras or playing chamber music. But as we open up again after months of lockdowns, I’m afraid for some of the young players just starting out. One of my students has had to cancel 30 concerts and it isn’t clear if these will come back. For the big established stars, the concerts will come back but for the youngsters I don’t know.

One thing I’ve noticed in recent years is that most young players are technically very good. That’s a big difference from my time, when the emphasis was not on technique but on the music. Today the first thing you hear in someone’s playing is their technique. At top competitions many of the players are from Asia, were discipline is high – this is very different from when I was a student, when the best players were from Europe and particularly Russia. The reason for this shift is the standard of teaching. All but a few great teachers left Russia because of the lack of money - they could earn ten times more in the West than in their home country. The same was true in Hungary, sadly. I am one of the last descendants of the great Hungarian violin school, starting with Joachim, then Hubay, then Zathureczky, then me.

György Pauk’s autobiography ‘A Life In Music: Memories of 80 years with the violin’ is on sale now. Click here for full details.

No comments yet