The position of the fingers on the bow can make all the difference to dynamics and tone production. Rok Klopčič examines the bow holds of leading violinists and pedagogues, in this feature from October 2007

Traditionally, Carl Flesch’s classification of three main bow holds in his book The Art of Violin Playing has dominated discussions about the ideal position of the right hand. I believe that these classifications focus on matters of relatively minor significance. Instead, here I will look at the element of bow hold I consider the most important: the position of the fingers in relation to that of the thumb.

Consider the thumb, fixed at the end of the frog, as the centre of all bow holds. Then, the crucial aspect to examine is the variation in the distance of the four fingers from this centre in the technique of different players. Without moving the thumb, the rest of the hand can glide up or down the stick, towards or away from the point of the bow. Every tiny change in the distance of the fingers from the thumb influences the entire technique of the right hand and can change the quality of the tone produced. It is therefore worth investigating the different ways in which this aspect of bow hold has been approached by various artists, and which techniques have been recommended by different teachers. Looking at the possibilities and the players who used them can help us reach a better understanding of the options and their varied effects.

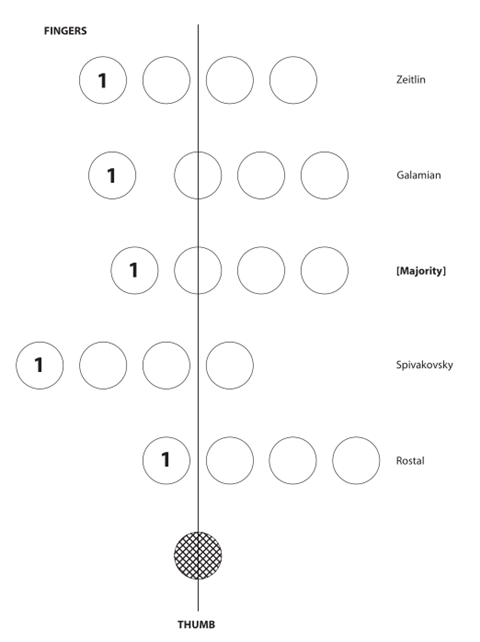

Two very different violinists, Max Rostal and Tossy Spivakovsky, recommended quite different positions for the hand in relation to the thumb. In his book Handbuch zum Geigenspiel, Rostal put forward the view that the thumb should be under the first finger or between the first and second fingers.

I played using this technique for several years and would not recommend it. Spivakovsky preferred a position that placed the thumb under the little finger, or between the third and little fingers. His bow hold may have contributed to his excellent tone, which I was able to admire during his recital at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 1957.

I was not alone: Samuel Applebaum referred to Spivakovsky’s legato during this performance as ‘miraculous’. After reading Gaylord Yost’s thought-provoking book The Spivakovsky Way of Bowing I experimented for a few days with this bow hold, unfortunately without encouraging results. However, Spivakovsky’s shining example arguably justifies further experimentation: there may be some violinists who have an aptitude for this technique.

In Samuel and Sada Applebaum’s book With the Artists, Harold Berkley is quoted as saying: ‘Most artists agree that the centre of balance is between the thumb and the second finger.’ This view is upheld by various books and articles in which other artists and teachers reveal a similar belief in the synergy between the thumb and the second finger. Paul Rolland refers to the ‘fulcrum’ and the ‘axis’, Demetrius Dounis to ‘the centre point’ and ‘the centre of the hold’, Lucien Capet to ‘le centre’, Ivan Galamian to the ‘circle’ and Isaac Stern to ‘the centre of pressure, the circle’. Pierre Baillot, Henryk Wieniawski, Abram Ilich Yampolsky, Percival Hodgson and Yehudi Menuhin are also known to have shared a belief in this bow-hold technique.

When the bow is held in this manner, a fulcrum is created by the thumb and second finger, with a lever on each side: the first finger exerts positive pressure, and the fourth finger negative pressure. The application of both kinds of pressure is essential to attain a dynamically even tone: on a down bow, when the bow is approaching its tip, it is necessary to increase the positive pressure; on an up bow, when the bow is approaching its frog, negative pressure should be applied. These are the basics, but various artists have found ingenious ways to create a fuller, stronger, more beautiful tone with less physical effort, by making additional small changes in the placement of the fingers and in the bowing action.

Every change in the distance of the fingers from the thumb influences the technique of the right hand and can change the tone quality

In my opinion, the most valuable adjustments to the basic position of the fingers are those made by Galamian and Lev Zeitlin. Both violinists made adjustments that put more emphasis on the lever for positive pressure. Zeitlin did this by moving the hand further towards the point of the bow, so that the thumb is between the second and third fingers; Galamian created the ‘Galamian spread’ by ‘placing the first finger at a slight distance from the second finger’. Galamian’s method is well known, though Josef Gingold put forward the opinion that Galamian renounced it in his later years. Zeitlin’s renown has not spread far outside Russia, and his idea is not widely known. But his bow-hold philosophy is interesting for two reasons.

First, it shows that there was no uniform Soviet or Russian school of violin playing: Zeitlin’s contemporary Yampolsky was an advocate of positioning the thumb under the second finger. Second, Yuri Yankelevich was familiar with this method and recognised its drawbacks: ‘The result of Zeitlin’s quest for a strong, big tone and a dense contact of the bow with the string did, to some degree, make the playing of the “light” bowings more difficult.’ Is it possible that Galamian himself experienced similar doubts about the Galamian spread.

As well as the position of the fingers, the pressure applied by them is of crucial importance. Stern proposed the promising idea of applying more pressure to the bow with the second finger and the thumb. He said: ‘I exert a good deal of pressure with the middle finger and the thumb.’ Hodgson described it thus: ‘The second finger presses downwards, and the thumb upwards. When the first finger is added… the transmission of any necessary power appears to be effortless.’ The same procedure was suggested by Dounis for parlando bowing: ‘The main pressure is chiefly achieved by the thumb. It presses upward against the first finger.’ All three violinists apparently supposed the second finger to be opposite the thumb, but I believe that for this pressure to be really effective the second finger should be moved a miniscule – almost imperceptible – distance away, towards the point of the bow.

Another aspect of bow-hold technique to consider is the feeling that should be retained in the right hand. Some violinists have described this vividly: Berkley wrote about a ‘springy, almost spongy, feeling in the knuckles’, and Galamian makes reference to a ‘system of springs’ and ‘resiliency and the springiness in the functioning of the whole arm from shoulder to fingertips’. This consideration of the whole of the right arm when holding the bow, with a horizontal straight line from the elbow to the hand, together with the thumb being opposite the second finger, is now very much the norm for the majority of violinists worldwide.

Several years ago, while serving as a jury member during the Lipizer Competition in Gorizia, I asked a few of my colleagues who they thought had initiated the bow hold centred around the thumb and second finger. Nobody knew the answer – and neither do I. But let me suggest two influences: Berkley’s book The Modern Technique of Violin Bowing, and the playing of Stern, whose bow hold presumably resulted in his miraculous tone. I would also speculate that a lecture given by Pablo Casals in Paris immediately before the start of the Second World War may have had an effect. When I asked Henryk Szeryng about his own bow hold he implied that he’d been influenced by Casals’s lecture, and he told me how the audience had reacted to Casals’s idea. Apparently Casals’s pupil Diran Alexanian said: ‘He’s my master, but this is mad!’

FURTHER READING

- Samuel and Sada Applebaum With the Artists

- Percival Hodgson Motion Study and Violin Bowing

- Yuri Yankelevich On the Early Stages of Teaching Violin

Read: 7 bow hold insights from historical string players

‘We should always listen carefully to the quality of our tone’ - Technique: Working on open strings

Cellist Denis Severin provides exercises to help you build up a strong, reliable right hand, with a consistently beautiful sound

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Violin Bow Hold: No holds barred

No comments yet