A student’s earliest engagement with note reading is the right time to introduce sightreading, argues Naomi Yandell

This article was originally published in August 2017

Like many teachers at this time of year I am preparing to return to work. I shall shortly be welcoming back ongoing students as well as getting to know an influx of new ones – both beginners and some inherited from other teachers. To date I have acquired students with a range of strengths and weaknesses, and as I assess my incoming students I can guarantee that sightreading is most likely to be a weakness. Some of them put on what I call a ‘sightreading face’ and play tentatively, as if they’ve been sent to the headmaster’s office having done something unforgivable. Some play the notes in the correct order but without any sense of the rhythm. Others refuse to try. And then there are those who give me a sidelong look and ask me to show them how it goes. Heigh-ho.

I see why some teachers don’t start note reading from the beginning: they would rather focus on aural skills, finding that note reading gets in the way of the student’s relationship with the instrument and the music. Absolutely. But once students begin to read notes, sightreading should be taught. This will lead to the freedom to enjoy exploring repertoire outside their lessons. It’s sad but true that some students are so overwhelmed by the prospect of sightreading that they leave rather than attempt it without fingering written in by their teachers.

So I micromanage their thought process in lessons as they prepare to sightread. That way, they have the tools to approach it without panicking. Whether the pupil is new or inherited, this always means explaining that pulse and rhythm are more important than playing the correct pitches (though that, of course, would be ideal). I ask them what would happen if everyone went back to correct their wrong notes in an orchestral situation (even the youngest student can work that one out).

Then follows a kind of sightreading brain gym, whereby I ask the student to speed-read the music, picking out the tricky sections so that they know where to focus their attention in the few seconds they have before playing it. This involves them singing the exercise along with me, noticing how the sounds move up or down with the noteheads, and playing any scale fragment that they can see and spotting the changes necessary for the key signature – all while I run my finger, or bow, along the music at the speed at which they might play it. Reaction speeds are important.

I find that introducing the concept of ‘traps’ in the music is useful and fun. Young students respond well if they think it’s their job to outwit the composer and play the music correctly. A trap could be a long note at the start of a passage: if they haven’t worked out a suitable pulse for the opening minim, how are they going to be able to keep up when the rhythm includes quavers further into the music? As we work together, students start coming up with their own observations. Perhaps they will begin to use words from Dalcroze sessions to help with the rhythm or come up with the idea of playing a left-hand pizzicato to solve a quick arco–pizzicato transition.

At the heart of everything to do with sightreading we talk about performing rather than playing the music, catching the flavour of the piece and giving it our best shot. Never mind a few rough edges.

In the likely event that sightreading fazes my newly inherited students, they can expect a lot of really easy sightreading to increase their confidence. The other day I received a phone call from a good friend of mine whose son is learning the cello. She was in a panic.

‘He has an exam in a week’s time and he can’t do the sightreading! He says he hasn’t done any with his teacher.’ As I reached for my computer to give the unfortunate child a ten-minute crash course via Skype, I found myself wishing that the teacher concerned had taken the time to include this element in their teaching. Like performance presentation it’s all in the preparation. And it’s a shame, but you can’t do it in ten minutes.

Naomi Yandell is a Cambridge-based music consultant, cello and theory teacher, author and editor. She is author of the Trinity College theory workbooks (Grades 1-8) and co-author of the ‘First string note book’ series for Bridge Music Publications

Image: Violin Lesson by Tom Roberts (1889)

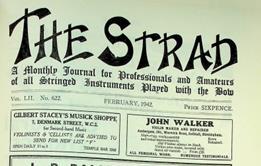

'It is even unnecessary to know the names of the notes' - From the Archive: February 1942

Violin pedagogue Percival Hodgson advocates a system of pattern recognition to help young players, rather than the laborious method of learning the names of notes

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Sightreading is a skill that should be taught early

- 7

No comments yet