Advice from The Strad’s archive on how to improve sightreading and reminders of its crucial place in any good musician’s skillset

The Wohlfahrt etudes served a valuable pedagogical purpose for me in addition to training my technique and musicianship. Whenever [Roland] Vamos assigned a new one, he would put it on the music stand and have me play it through two or three times to develop my sightreading skills.

The metronome would be set to a tempo slightly faster than was comfortable, and I had to keep going regardless of any mistakes I might make. Only after this sightreading practice did I learn the notes slowly and carefully on my own, paying close attention to the rhythmic relationships between notes of different lengths and checking all of the accidentals for accuracy.

Using etudes to improve my sightreading was really beneficial. While I was more or less familiar with most pieces of concert repertoire from recordings or the class performances of fellow students, the etudes were always new to me. They weren’t in my ear, so I had to learn to rely on my eyes. During my student years, being a good sightreader helped me to get studio and concert work, and to do well in orchestral auditions.

Today those same sightreading skills help to speed up the process of learning new repertoire and mean that when I have the chance to join in chamber music readings, I enjoy them even more.

Rachel Barton Pine, violinist, The Strad September 2011

On pursuing an orchestral career: Learn the whole craft of playing your instrument. This means playing chamber music along with the concertos you are learning and immersing yourself in orchestral music, even bringing excerpts to lessons along with your other repertoire and exercises. Why work on Gaviniès when you could work on Wagner, which is twice as difficult and more practical? Learn to sightread well: time is money and a recording engineer isn’t going to wait while you are learning the notes on the session.

Learn a new piece of music every week – even look at something new every day – to hone your sightreading skills.

Glenn Dicterow, concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic for 34 years, The Strad June 2014

From my own experience I can say how important it is, at all but the earliest stages of learning, for the teacher not to demonstrate a piece before the student has at least had a go at sightreading it.

I was a pathetically bad sightreader. I got distinctions in my exams but I usually either failed or just scraped through the sightreading test. Looking back, I believe that all my pieces were played to me first by my teacher, and having both perfect pitch and a very good musical memory, I managed to avoid the bother of actually reading the music. I only really learnt to sightread properly when I started playing in the pit for musicals, usually as leader of the orchestra. It’s amazing how much that improved my sightreading.

As a teacher, I have always encouraged pupils to have a go at each piece themselves, however badly, before I play it to them. I also have a wide selection of duets we can sightread together, which helps resist the temptation to go back and correct mistakes.

Anne Dales, violin teacher, The Strad July 2015

Think in blocks, positions, in the same way a pianist would. Then when you move your hand the notes are just where the fingers lie. That is also a general piece of advice for sightreading – one should be looking for the groups; but it’s particularly important when you’re trying to minimise physical movement so that there’s an even sound.

Tim Hugh, cellist, The Strad June 2006

Before allowing a pupil to sightread, we should always be reasonably certain that they will get it right. Fluency will not be possible if there is the slightest hesitancy in the recognition and understanding of either pitch or rhythm.

It will also be hampered if pupils are not taught to disregard errors – the psychological effect of making a mistake is often the cause of hesitancy.

Paul Harris, pedagogue, The Strad May 2001

The essentials of good sightreading:

- Observe the time signature and tempo

- Study the rhythm

- Be aware of the key signature and the notes to which accidentals apply

- Look for strings and positions

- Identify shape and movement of phrases

- Observe dynamics and articulation

- Spot key and time signature changes while clapping, tapping or vocalising the rhythm

Not until the student is armed with this knowledge should they play the piece. Then they can play it as many times as it takes to learn it. This preparation will, with practice, become quicker. In time, a scan of the rhythms will highlight all the other elements until a good performance can be given on a first attempt – as the student will need to do in an exam or audition.

Playing a piece once after a brief 30-second glance is something that only the exam boards require, and to many people it is a quite unrealistic requirement during the early stages of learning, and has a detrimental effect on students’ attitudes to this skill. Examination sightreading tests are also often illogical and unmusical, lacking the repetition of melodic and rhythmic shapes so often found in established styles. There seems little value in just giving ‘practice tests’ without having first learnt how to approach the skill in the logical and methodical way outlined above.

John Kember, pedagogue and former ABRSM examiner, The Strad September 2007

Most adjudicators will confirm that sightreading tests are the most creatively performed part of any audition or exam – creative in the sense that the attempts bear scant resemblance to the printed page.

Some of this imprecision can be attributed to nerves, but the basic flaw ties in with the early stages of learning an instrument. In too many cases students simply do not know where the notes are, and are not fluent enough in producing a rhythmic pulse. The consequence is that reading skills are fairly basic.

When children learn to read text at school they practise with hundreds of books, but students often work exclusively on a few exam pieces, which they sometimes take a surprisingly long time to learn. Inevitably sightreading suffers, yet it is the one vital skill that will enable the student to become sociable by playing in ensembles.

Joanne Talbot, The Strad December 2006

I see why some teachers don’t start note reading from the beginning: they would rather focus on aural skills, finding that note reading gets in the way of the student’s relationship with the instrument and the music. Absolutely. But once students begin to read notes, sightreading should be taught. This will lead to the freedom to enjoy exploring repertoire outside their lessons.

I micromanage their thought process in lessons as they prepare to sightread. That way, they have the tools to approach it without panicking. Whether the pupil is new or inherited, this always means explaining that pulse and rhythm are more important than playing the correct pitches (though that, of course, would be ideal). I ask them what would happen if everyone went back to correct their wrong notes in an orchestral situation (even the youngest student can work that one out).

Naomi Yandell, cellist and pedagogue, The Strad September 2017

On the importance of scale practice: A fully worked-out system of fingerings for each scale negates the old belief that C major is easier than C sharp major or that E flat minor is more difficult than E minor. Thanks to the flawless organisation and discipline of a system, the scales all follow the same principle, allowing the key and its fingerings to be immediately identified.

Much will eventually rely on muscle memory, so that in the end you find yourself more occupied with drilling the muscle memory than with notes. The philosopher Friedrich Schlegel warned: ‘It is equally fatal for the mind to have a system and to have none. One must try to combine them.’ Such an attitude promotes a flexible mind and is a giant step towards the release of the imagination, but it would only interest me once I had acquired a system in the first place.

A system is also excellent for sightreading when you need to identify an approaching scale or passage quickly.

Mats Lidström, cellist, The Strad April 2012

And finally…

Many orchestral string players emphasise that good faking is an essential facet of really good sightreading, involving as it does that certain modest recognition that one’s personal genius must be sublimated to the good of the whole. Meanwhile, a player in a famous American orchestra, who cut his finger on an anchovy can and was thus obliged to fake perfectly playable bits of one concert, spoke with humility of realising how marvellous his orchestra sounded without him!

There is no doubt that faking has an ancient and historic pedigree. Hans Richter, who in 1876 conducted the first Bayreuth performance of Wagner’s Ring, was once confronted by a despairing violinist who said, ‘How is a man to play this complicated figuration? What can he do but go a-swishing up and down as best he can?’ To which the Maestro replied, ‘What, indeed? That is precisely what the composer intended!’

Alice McVeigh, cellist, The Strad June 2006

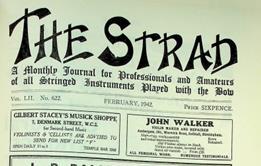

'It is even unnecessary to know the names of the notes' - From the Archive: February 1942

Violin pedagogue Percival Hodgson advocates a system of pattern recognition to help young players, rather than the laborious method of learning the names of notes

- 1

- 2

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

10 tips for learning and teaching sightreading

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

No comments yet