Taubman Approach specialists Edna Golandsky and Sophie Till examine how proper alignment in the right arm can help eliminate tension and allow for fluidity when bowing

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

When considering the tension and fatigue experienced by string players, the left arm is often the main culprit, as discussed in Edna’s previous Strad article. However, many violinists that come to both of us have serious problems in the bow arm as well. Common complaints are fatigue, pain throughout the hand, wrist, and arm often radiating up to the neck, and instability both while playing and getting to the string.

All of these problems stem from the incorrect position of the fingers, hand, and arm. Most string players understand that moving the bow is honed to the specifics of tone, colour, and articulation as demanded by the music. However, to accomplish this it’s important to learn certain physical rules that make this possible. The most basic of these rules is that the fingers, hand, and forearm - the parts that are involved in holding and moving the bow - have to be aligned.

We see the principle of alignment in action when holding objects in daily life, like a glass of water or a toothbrush. The fingers by themselves do not have much strength, so trying to hold objects with the fingers alone results in holding tightly. This in turn leads to tension in the fingers, hands, and arm. However, as soon as we connect the fingers to the hand and the forearm, the fingers can hold onto the object with little effort. This is true when holding the bow as well.

Another problem is isolating and stretching. In daily life, we don’t isolate the fingers and pull them away from each other, because, in addition to making it difficult to hold onto objects, it is also another main source of tension. This is also true when holding the bow.

Here are five ways isolation and lack of alignment may be causing tension in the bow arm and how proper alignment as adapted from the Taubman Approach can help minimise and even reverse these painful symptoms:

1.

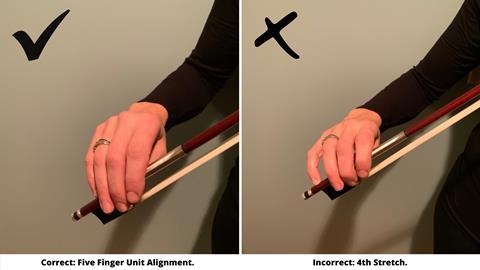

Isolation of the index finger and pinky. This occurs when the index finger is stretched forwards away from the rest of the hand and is used to exert pressure, while the pinky is stretched in the opposite direction as it tries to balance the bow. Even the smallest amount of separation causes this. In contrast, when the five fingers act as a unit, holding the bow becomes easy and comfortable and the arm is free of tension.

2.

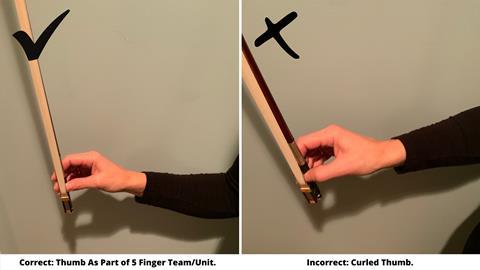

Isolation of the thumb: The thumb is also a part of the five-finger unit. Traditionally, the thumb is often trained to have an isolated role also, most notably by curling (an outward kink in the thumb knuckle). This is a frequent cause of pain in the right arm. Curling any of the fingers pulls the long flexor tight and creates tension throughout the finger, hand, and arm unit. When the thumb holds even slightly too close to the nail, it starts to curl and the resulting tension is evident. To resolve this problem, the finger needs to be in a natural position, which is a slight curve. The thumb should look the same on the bow as it appears when the arm resting at the side: neither curled in nor arched out. This position enables it to function as part of the five-finger team.

Read: Ask the Experts: how to eliminate tension in the bow arm and hand

Read: How to avoid tension in the bow arm, by cellist Bonnie Hampton

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playng Hub

3.

Isolating the hand and fingers from the forearm: As noted above, the fingers by themselves are not particularly strong on their own and therefore require the support of the hand and the forearm to hold the bow with ease within its limited capacity.

4.

Lifting and dropping the wrist. Another common break in alignment occurs when the wrist lifts, drops, or twists left and right. When that happens, the fingers can no longer access the forearm support and have to tighten and grip to hold, which leads to fatigue and pain throughout the finger, hand, and arm. However, when the finger, hand, and forearm are aligned, and the hand is a five-finger unit, the fingers can respond to the motion of the forearm with complete ease and in a subtle way.

5.

Initiating the movement: There is much confusion as to what initiates and what follows in the arm movement from left to right. The fingers and the wrist are not capable of initiating. Equally problematic is the upper arm and shoulder, both moved by large muscles that fatigue quickly and are not capable of quick motion. The part of the arm capable of initiating movement with the necessary ease, speed, and power is the forearm. The fingers, hand, wrist, upper arm, and shoulder follow in their proper proportion and in a synchronised way. This is particularly important as the bow arm moves towards the frog. When the shoulder and upper arm are free to follow, the basic alignment of the arm can be maintained, and the arm can continue to hold easily.

As we have discovered through in our work together to adapt the Taubman Approach principles to string players as well as pianists and computer keyboard users, these micro-changes add up to major results that can save instrumentalists from turning to life-altering surgeries or quitting playing altogether, and can improve their playing abilities beyond what they believed possible.

Edna Golandsky is a world-renowned piano pedagogue, the leading exponent of the Taubman Approach, and is the founder of the Golandsky Institute. A graduate of the Juilliard School, where she studied under Jane Carlson, Rosina Lhévinne, and Adele Marcus, Ms. Golandsky has earned acclaim for her pedagogical expertise, ability to solve technical problems, and her musical insight. Learn more about the Taubman Approach and her online symposiums and consultations here

Sophie Till is associate professor of violin and director of the String Project at Marywood University, Pennsylvania. She is also chair of the National String Project Consortium and faculty at the Golandsky Institute NY. Sophie’s work with Edna Golandsky at the Institute has led to the development of her approach to string pedagogy. She works internationally with many professional orchestral players solving playing-related injuries, in particular with players from the US, UK and Australia, and is the string specialist for the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra in the UK

You can learn more about Sophie and her work here

Read: How the Taubman Approach can help string players prevent RSIs

Read: Alexander technique: Thoughts that count

Read: 10 ways to avoid tension in your playing

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

1 Readers' comment