In an age where starting the violin at age three is considered ‘normal’, violinist Daniel Kurganov shares his musical journey of first picking up the violin as a teenager

Following a recent recital in NYC, a woman approached me to express her appreciation. I was in a bit of a daze from the performance, but my ears perked up when she said, ’You must have started when you were three!’

I paused for an eternal second and deliberated about whether to disabuse her. Why risk turning that look of joy into confusion? It has never been easy to explain that I first touched a violin at 16. Will people be impressed? Inspired? Judgmental? And who cares?

Let me back up. It’s 2002 and 16-year-old me is sitting in a theatre (remember theatres?) watching The Pianist—it was that scene where Szpilman plays Chopin for the SS officer who finds him in hiding. Like many Soviet children, I had studied piano throughout my youth. In my early teens, however, my obsession shifted to guitar after seeing Jimi Hendrix burn his instrument on stage in an act of showmanship. I threw myself into rock, metal, blues, jazz, and classical and left piano behind. But that day in the theatre I suddenly felt the purpose of music and how life could inform it. I fell in love with classical music and told my parents, ’That’s it. I want to be a pianist.’ I wanted to play Chopin like Szpilman!

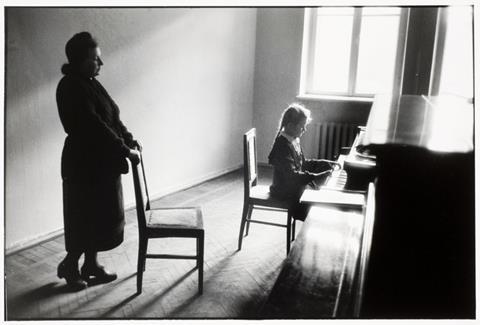

My understanding piano teacher Alla Danichkina (who also taught violin) humoured my desire to only play what I liked. And it was she who, along with my mother, one day encouraged me to try my hand at playing her violin just for fun.

It was love-at-first-scratch, we quickly pivoted, and after several months of intense practice, I switched to a very well-known violinist and his wife—first as a high-school student, then at conservatory. To me, they represented the ’old-school’ tradition which I adore, and I worshipped and admired them for that.

Over time, however, I began to understand with more confidence what I wanted. I didn’t yet know how to get there, but I knew what would hold me back. As a result, I began to go against their advice. Instead of celebrating my initiative and inquisitive nature, they subjected me to psychological abuse and even tried to sabotage my career before it started. My final year of conservatory was spent without a teacher.

Oddly enough, this was the year when I made the most progress to date. If I had started violin as a young child and had been trained to follow the teacher unconditionally, I might not have trusted my gut. Fighting conformity is easier when you realise that most people will conform to almost anything under enough pressure.

The next breakthrough fell into my lap after graduation. I was a full-on violin nerd by then and knew all of the great violinists, or so I thought. And then one night, during a typical YouTube vortex, I came upon an incredible violinist, Rudolf Koelman, who had been a student of Jascha Heifetz. To be sure, there were more sensible options for schools, but I knew I had to go where he was: Zürich. I had learned that I thrive when I watch, listen, imitate, experiment and then synthesise, and Europe immersed me in ‘the source’ of music. It felt like an orchard full of low-hanging fruit, and I had let go of the naive wish for an all-knowing, all-controlling Soviet-style pedagogue.

Consider a thought experiment: what if, instead of expecting musicians to have inoffensive intonation, smooth tone, control in all parts of the bow, tasteful rubato, adherence to the score as well as the ability to play in various historical styles—in a word, to be well-rounded—we embraced the freedom to be well-lopsided, allowing musicians to identify the tools and means of expression that suit them while discarding those that don’t? What effect would this have on the pressures that young musicians face, on competition standards and protocol, and on the ‘ideal age’ to begin study?

I am inclined to conclude that we would see greater individuality, happier young people, more creative competitions, more self-teachers and a more engaged audience. Highly individualistic and powerful artists live on the edge of failure. They are not well-rounded. And thank God for that.

I am very lucky to have parents who, while not being professional musicians themselves, trusted my passion through its twists and turns. But for many years, I wished I had started violin sooner, imagining how much ‘bigger’ my career might have been.

Now, though, I am grateful to have come to the instrument at an age when I could think for myself. I remember how I learned things, what worked and what didn’t, and all of my experimentation. And the twists and turns continue to inform my playing: the piano taught me pure love of harmony, jazz and blues gave me the freedom to improvise, and neoclassical metal gave me an appreciation for intensity and virtuosity. Classical guitar taught me intimacy and simplicity.

Our varied passions stem from and converge on the same place. Nothing is wasted.

Daniel Kurganov and Constantine Finehouse’s new album Rhythm and the Borrowed Past, consisting of works by Lera Auerbach, Richard Beaudoin, John Cage and Messiaen, is out now on Orchid Classics

Topics

Best of The Strad 2021

Rediscover your favourite online articles from the year

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Daniel Kurganov: on starting the violin at age 16

- 9

1 Readers' comment