In 2016 the ‘Messiah’ Stradivari was the subject of an extensive CT scanning project. Francesco Piasentini and Gregg Alf examine the resulting data, discovering repair work in the neck, and attempt to determine how it had originally been set

The following is an extract from an article in The Strad’s January 2021 issue in which we examine the findings of an extensive project to CT-scan the Stradivari’s iconic 1716 violin, the ‘Messiah’. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The January 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

The date was Monday 5 September 2016 and Francesco Piasentini, a violin maker with a PhD in metallurgical engineering, was waiting at TEC Eurolab, a leading company in non-destructive testing near Modena, for the return of the ‘Messiah’. At 11am Gregg Alf, a fellow violin maker and expert from Cremona’s Museo del Violino (MdV), would be delivering one of the rarest violins on earth. Accompanied by Fausto Cacciatori and Colin Harrison, curators from the MdV and Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum respectively, Antonio Stradivari’s iconic 1716 violin was returning to the city of its birth in celebration of its 300th anniversary.

With assistance from the Ashmolean, Cacciatori and Alf, aided by a team of experts from the MdV’s Arvedi Laboratory of Non-Invasive Diagnostics, had devised a programme of scientific inquiry that would respond, point by point, to questions left unanswered by experts before them. On the day of the violin’s arrival in Italy, its first stop would be a few hours at TEC Eurolab for a series of industrial computed tomography (CT) scans.

Read: CT-scanning the ‘Messiah’

Read: Postcard from Cremona: ‘Messiah’ Study Day 2016

X-rays of the past provided snapshots of physical conditions invisible to the naked eye. But CT scanning, made by merging thousands of X-ray-like images into a three-dimensional volume viewed with special software, allows an unprecedented view of conditions below the surface. Directed by Alf’s keen awareness of the issues and guided by Piasentini, who as a CT consultant has developed several applications for the study of bowed stringed instruments (with the support of TEC Eurolab’s team), today’s scanning would hopefully provide useful information for a worldwide community of violin makers.

As the first radiographic images of the ‘Messiah’ began appearing on the monitor (figure 1), it was clear that the instrument presented unique and unexpected features. Of particular interest were remnants of old iron nails still present in the neck heel, and a single metal screw that appeared to be the only attachment now securing the violin’s neck to its non-mortised body.

-

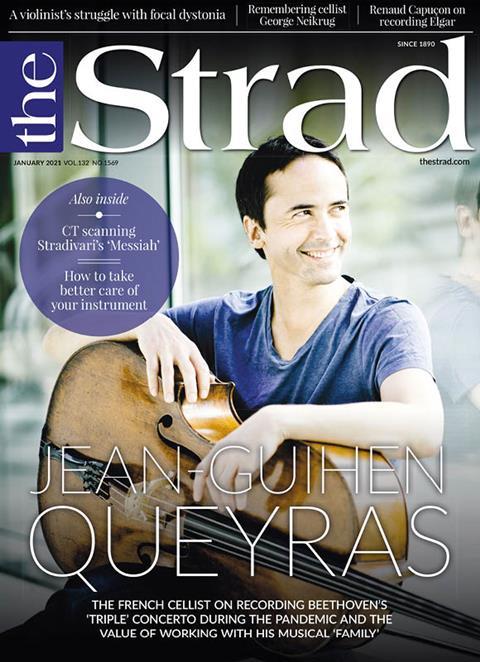

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue.Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

- CT scanning Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’

- Remembering cello tutor George Neikrug

- Renaud Capuçon on recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- How players can take better care of their instrument

- Playing Tchaikovsky with just two left-hand fingers

Read more lutherie content here

No comments yet