This photo was published in the The Strad May 1989 where it featured on the cover as well as being that issue’s poster. The accompanying article, from which the below is extracted, is written by Roger Hargrave. The photos are by Stewart Pollens

The name Betts crops up again and again in the history of many fine instruments. Betts was a famous (one might say infamous) London firm of dealers and makers who were responsible for importing a large number of Italian works into Britain in the first half of the 19th century. No individual piece, passing through this firm’s hand however, was destined to cause as much excitement as the 1704 violin by Antonio Stradivari which now bears their name.

Legend had it that the sum of one pound was paid for the instrument, that a family row broke out over ownership, and that this row eventually led to the dissolution of the Betts family partnership. In 1852 after the death of Arthur Betts, the violin was in the possession of John Boue, a retired judge who subsequently sold it to J. B. Vuillaume. Before the turn of the century the violin was inevitably acquired by Hills of London.

…

In 1704 Antonio Stradivari was sixty years old, a time when most men might be thinking of slowing down and taking life easier. Stradivari, however, was on the threshold of his maturity as a maker and there are those who would maintain that the ‘Betts’ violin marks the true beginning of his golden period.

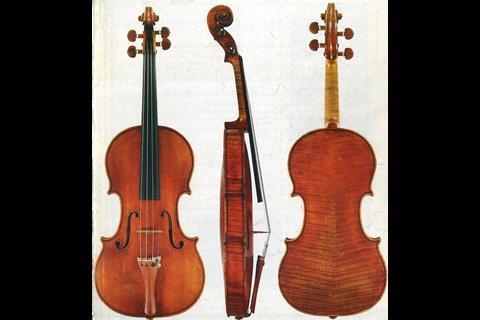

Quite apart from the obvious innovative qualities of the year in question, the ‘Betts’ itself is a genuinely an overwhelmingly attractive violin; nothing was spared in its concept, its construction or the materials from which it was fashioned. The straight-grained, two-piece belly is of fine growth becoming very slightly wider in the flanks. It is as attractive a piece of wood as one could wish for, with a suggestion of hazel in places. As would be expected it is cut perfectly on the quarter.

…

The quarter-sawn backwood, also of two pieces, has strong, deeply curling flames sloping upwards from the centre joint. Like the belly it is imported wood. The ribs may well have been cut from the back, which they closely resemble. Here the flame has a slight slope running upward from left to right off the back. As is usual for Stradivari the figure on the ribs flows in the same direction all around the instrument.

…

It almost seems as if, in the year of the `Betts’ violin, exactly 20 years after the death of Nicolo Amati, Antonio paid one last tribute to the finest of Amati styling by combining it with the maturing grandeur of his own work. The outline of the `Betts’, with its elegant long corners and the corresponding long purfling mitres, so reminiscent of the Amatis, was never repeated in the years which followed. The effect which this combination creates is that of a cultured beauty, with a forceful personality and a mature temperament.

…

The soundholes are upright and strong in appearance but with no sign of stiffness. Like the outline they balance each other almost exactly in both position and shape. Such mathematical harmony is rare even for Stradivari. The exceptionally high calibre of the work on this violin from top to bottom is epitomised in the work of the soundholes.

…

Although relatively thin, the varnish is intensely coloured. It is present in large amounts and it has a fine Craquelure which has mercifully not been polished out.

No comments yet