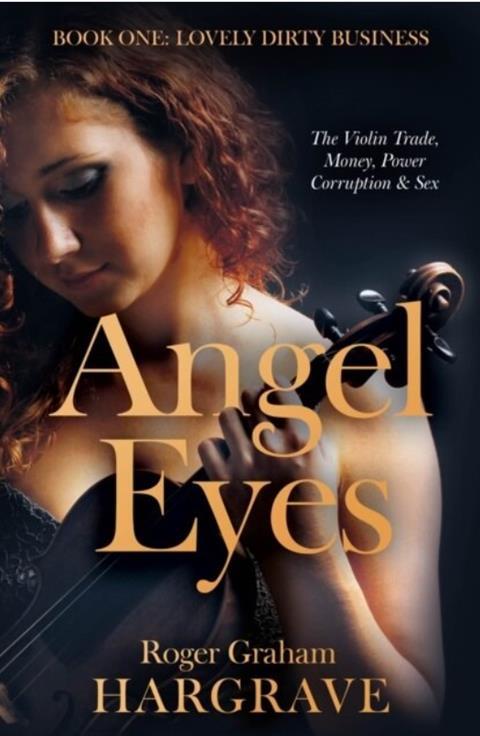

Anne Inglis reviews the first in a projected quintet of novels by Roger Graham Hargrave centred on the violin business

Angel Eyes

Roger Graham Hargrave

376 PP ISBN 9781805142027

Troubador Publishing £9.99

It is interesting how life turns about. I start with a little personal history to set this review in context. Back in the 1980s, during my editorship of The Strad, Roger Hargrave was one of my stable of writers who put the integrity of the magazine’s violin knowledge on the map. Through his links and my persistence, writers of the calibre of John Dilworth also made their invaluable contributions on the same pages. Hargrave was responsible for introducing the colour posters that changed the lives of so many violin makers, with their accurate colour reproduction and, more importantly, the detailed measurements. Initially he delivered his writing in longhand, as did other contributors, so keen was I to include their words of wisdom and straightforward expertise. Hargrave was a game changer.

Now at the other end of his working life, Hargrave has distilled his knowledge into a series of novels, the first of which has been published with the remaining four on the way. He is keen to underline the disguised characters, locations and anything else that might point to identifying the sources of some of the juicy stories and plot lines included.

He has spread his canvas wide, and the fluent writing and accessible content should appeal to a broad readership of players and luthiers, amateur and professional, and not just the inner circle of curious violin makers. The violin world is still full of secrecy, despite Hargrave’s efforts to dispel some of the myths, and this book (I have also read excerpts from the next novel) manages to combine raw detailed expertise in the history of violin making, and what to look out for in the making of individual makers, all in the readable narrative.

Read: Making a double bass - a blog by Roger Hargrave

Read: Baroque Instruments: Evolutionary Road

Read: Re-rediscovering the lost secrets of classical varnish

This is combined with the story of a woman who is tutored in the knowledge of violin making by her father and grandfather, and whose personal life is also a significant thread. The narrative of a young girl’s personal journey, in life and love, is told with real fluency and flair, although the many references to Grace being ‘fat’ did jar. The writing about sex cannot be ignored, and is graphic at times. This sits awkwardly within the narrative and isn’t needed to hold the reader’s attention. Others might enjoy this lurid detail more than I did.

The story is initially set in America, then moves to London, and I imagine will go further in the subsequent novels. There is a terrific amount of interesting historical background, and there were moments when I wondered if I was reading a historical treatise, a graphic love story or a violin family tree. There is didactic storytelling as Hargrave tries to include a mass of information, whether on the Po Valley, class divisions, the development of jazz and its relationship with the radio, and even some interesting explanation of the role of the ship’s surgeon on the Queen Mary.

But I especially appreciated the thread about the Nazi appropriation of violins. If paintings, why not violins? This rang worryingly true, and the book opens post-war with a series of fine instruments being taken from London to the US to be dispersed.

The innate secrecy of the violin world means that the core details of identification are often hidden, and known by the few who have had access to seeing the finest. The selling of instruments is unregulated, save by those experts who profit from the exchanges, and this aspect of the trade receives welcome attention within the storyline of this absorbing novel.

Anne Inglis

No comments yet