In this extract from the February 2022 feature, Louise Lansdown examines how the long-distance teaching partnership of the Arco project facilitates musical story-telling, thanks to cross-collaboration of different cultures

Photo: Jan Repko

An Arco group ensemble class at the Morris Isaacson Centre for Music (MICM) in Soweto, South Africa, in 2017

The following extract is from The Strad’s February 2022 issue feature ‘Arco project: Evolution of a partnership’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The February 2022 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

Cultural tensions

The challenges faced by teachers expose a deeper issue. The blending of two cultures always presents difficulties. And the fact that Arco is operating as an educational project in post-apartheid South Africa means that cultural differences are especially important to notice and address. Differences, and even tensions, could be seen in all aspects of the Arco project.

One South African teacher noted that Western classical instruments were sometimes viewed as ‘foreign to our culture’. Similarly, using Western repertoire in teaching posed issues of cultural relevancy. However, by the time the research report was written, Arco had already begun to address these sensitive issues. As one MICM teacher put it:

I always tell my students: ‘A story is a story – it doesn’t matter what culture or whatever. If your craft is to tell stories… you have to learn to tell that story.’ After all, we are not a cultural group; we are here to practise a craft. The kids play enough South African music in the centre, which I’m very proud of. We’ve done quite a lot of locally relevant music.

String playing is about more than technique or standard repertoire. It is, for this teacher, about telling stories, and students certainly benefit from the opportunity to tell their own musical stories. Teachers benefit, too, and while this research project progressed, Arco festivals began to incorporate more South African music, which UK student teachers learnt by rote.

One MICM teacher’s response to an interview question exposed a more fraught issue. They reflected on how, ‘When we first started Arco I found it was a bit of a racial thing and I know I wasn’t the only one having that same problem.’ This teacher observed that: ‘The kids for some reason kind of felt that the [UK-based] Arco teachers knew what they were doing better than we [South African teachers]’ – many of whom had had strong training as players and teachers. Countless assumptions and concerning biases are bound up in this observation. What is most important is how deep certain biases can run: students were reaching assumptions that one culture produced better teachers even without those assumptions being suggested or reinforced by their teachers.

Read: Arco project: Evolution of a partnership

Read: Postcard from South Africa - ‘What It Takes: Double Bass’

-

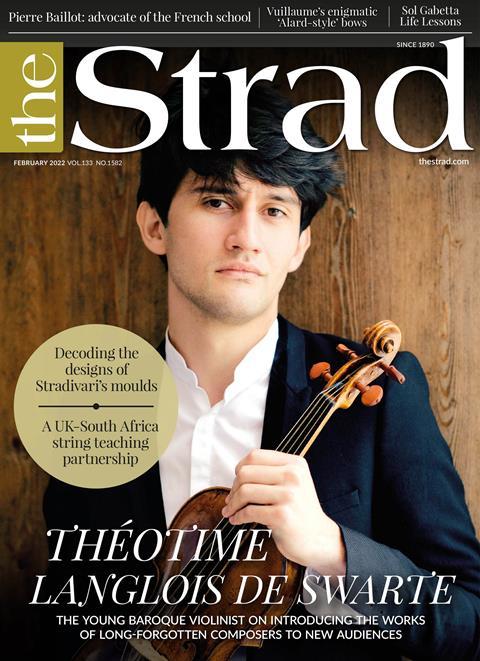

This article was published in the February 2022 Théotime Langlois de Swarte issue

The Baroque violinist’s career has taken off in the past year. Charlotte Gardner talks to him about his quest to popularise the works of long-lost composers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Théotime Langlois de Swarte

- Vuillaume’s ‘Alard’ Bows

- Pierre Baillot

- United Strings of Europe

- Cremonese Violin Moulds

- Arco Project

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet