In honour of Nathan Milstein's 110th birthday today, The Strad revisits a ‘Great Violinists' article by Julian Haylock, published in the September 2009 issue

Celebrated for his technical ease, aristocratic poise, mellifluous bowing and tonal perfection, Nathan Milstein sustained a professional career at the highest level into his early 80s.

PEDAGOGICAL BACKGROUND

‘I started to play the violin not because I was drawn to it, but because my mother forced me to,’ Milstein once candidly admitted. Those beginnings were in 1907 and just three years later he began his formal training with Pyotr Stolyarsky, celebrated teacher of David Oistrakh, although he later claimed, ‘Stolyarsky never taught me anything.’ Whatever the truth of the matter, within five years Milstein was one of Leopold Auer’s most renowned students in St Petersburg. On reflection, Milstein felt that he learnt more from observing the cream of young Russian musical talent and seeing Feodor Chaliapin perform the title role in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov than he ever did from his teacher. When Auer left Russia for Norway in 1917, the 13-year-old virtuoso with the bewitching ‘Black Sea’ technique was effectively left to fend for himself.

TECHNIQUE AND INTERPRETATIVE STYLE

Milstein always insisted that anyone could acquire the basics of mechanical technique with sufficient practice, and that the real work and inspiration began with developing a unique expressive sound world. In conversation with Pinchas Zukerman, he once described his main concern in starting a piece as ‘not spoiling its mood’. Perhaps that is why he spent a lifetime finding different ways of facilitating his musical vision with alternative bowings and fingerings until a piece sounded exactly as he envisaged it in his mind’s ear. Simplicity was Nathan Milstein’s ultimate aim, so that his audience knew exactly what he was saying through the instrument without any technical impurities coming between them and the music.

Milstein was not blessed with large hands, but they were extraordinarily supple and often gave the strange impression that he had no bones or joints in his fingers. In fact, the fingers of his left hand achieved their miraculous clarity through firm, precise placing, which was achieved with the minimum of height or extraneous movement. Even when notes came teeming off the fingerboard, Milstein’s left hand often appeared to be moving in slow motion, as though it was gently feeling its way around the notes.

Milstein’s fabled purity of intonation was achieved in part as the result of his acute sensitivity to the natural harmonics of the violin. Particularly when he was playing in one of the four open-string keys, one could sense an extra brightness to the sound as he honed in on his instrument’s natural resonances. His vibrato was as undemonstrative as his general playing style, regulated on the fast and narrow side of medium, and often reduced to nothing, especially in slow passages in which he would often emulate the ringing sound of a natural harmonic by using no vibrato on selected notes.

Milstein’s bowing technique was as effortless and undemonstrative as his stage persona. Perhaps its most unusual feature was his insistence on generating each stroke of the bow from his right shoulder. This negated the sense of angularity that can occur when working from the wrist, forearm or elbow, and facilitated his legendary ‘sweeping’ bow, which at a relatively low pressure almost glided over the instrument to create the most seamless legato of any violinist. By cushioning each stroke from the shoulder, he was able to change bows even in the middle of a note without disturbing the music’s natural flow and phrasing, hence his almost total avoidance of traditional staccato bowing.

SOUND

The ringing purity of Milstein’s sound was due largely to the profound rapport that existed between his left and right hands. His highly articulate fingering hand allowed him to bow with relatively low pressure and in long, gliding strokes, which resulted in a singing tone that appeared to arise from the inner soul of his instrument. To avoid impeding the violin’s natural voice and to maximise physical contact with the instrument’s resonances, Milstein never used shoulder rests or pads.

STRENGTHS

Everything about Milstein’s playing was supremely fluid and natural. Because there was no tension in his mechanism, his sound emerged unblemished and radiantly pure. He particularly excelled in music that tantalisingly combines intensity of expression with noble restraint, most notably the Mendelssohn E minor Concerto.

WEAKNESSES

Milstein’s self-effacing artistry and unflappable stage presence could create the impression of slight aloofness. His refusal to play to the gallery and restrained eloquence of voice thrilled aficionados of great violin playing, but often gave musical sensation seekers nowhere to go.

INSTRUMENTS AND BOWS

In 1934 Milstein acquired the 1710 ‘Dancla’ Stradivari, but from 1945 his main instrument was the 1716 ‘Goldman’ Stradivari, which he later renamed the ‘Marie-Thérèse’ after his wife and daughter. This stayed with the family until 2006, when it was sold to millionaire businessman Jerry Kohl, who now makes it available to gifted players, most recently Martin Chalifour (concertmaster of the Los Angeles Philharmonic since 1995). Milstein is also known to have played the 1717 ‘Reiffenberg’ Stradivari, whose most recent owners have included Jaime Laredo, Salvatore Accardo and Dmitry Sitkovetsky, and the 1727 ‘Milstein’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. His favourite bow was the ‘Milstein’ François Tourte, made in Paris around 1812.

REPERTOIRE

At the core of Milstein’s repertoire were the solo Sonatas and Partitas of Bach. Whereas the prevailing interpretative tendency was to ruminate imposingly and dispatch those infamous contrapuntal lines with a predominately vertical thrust, Milstein was all about natural horizontal flow and expressive ease. In Classical music – as witness self-directed recordings of Mozart’s K218 and K219 concertos, and a disc of Mozart sonatas with Leon Pommers – the serenity of his musical vision could seem almost too self-effacing, yet in Romantic repertoire he achieved a remarkable run of successes, most notably with the Mendelssohn E minor, Saint-Saëns B minor, Brahms, Goldmark, Glazunov, Tchaikovsky, and Dvo?ák concertos. His innate musical conservatism resulted in his neglecting many 20th-century pieces, so that although he recorded both Prokofiev concertos and played the Stravinsky, he bypassed the concertos of Sibelius, Elgar, Walton and Bartók. He adored the Berg, but plans to absorb it into his repertoire came to nothing.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of his artistry was his success with virtuoso showpieces. There was something about the combination of Milstein’s unflappable ‘cool’ with the outsize demands of such popular encore items as Wieniawski’s Scherzo-tarantelle, Novácek’s Perpetuum mobile, Sarasate’s Introduction and Tarantella and Milstein’s own solo Paganiniana that proved irresistible both in concert and on disc.

RECOMMENDED RECORDINGS

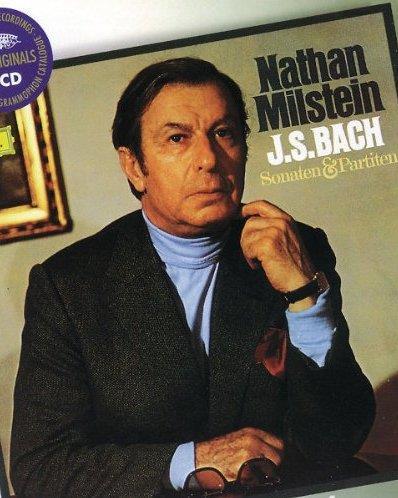

Bach: Sonatas and Partitas (complete) DG 457 701-2 (2 DISCS)

Beethoven and Brahms: Violin Concertos EMI 5 67583 2

Dvo?ák and Glazunov: Violin Concertos NAXOS 8.110975

Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky: Violin Concertos VAI 4279 (DVD)

Prokofiev: Violin Concertos EMI 4 76861 2

Nathan Milstein: A Portrait CHRISTOPHER NUPEN FILMS A 06 CND (DVD)

ESSENTIAL FACTS

1904 Born in Odessa, Ukraine

1916 Begins lessons with Leopold Auer

1921 Tours Russia with Vladimir Horowitz

1929 US debut with Leopold Stokowski

1932 UK debut with Malcolm Sargent

1948 Records Columbia’s first 12-inch microgroove LP (Mendelssohn with Walter)

1968 Receives France’s Légion d’honneur decoration

1975 Awarded Grammy for Bach Sonatas and Partitas

1987 Gives final performance, aged 83, in Stockholm 1992 Dies in London, aged 88

This article was first published in The Strad, September 2009. Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase back issues

No comments yet