Peter Quantrill finds a mix of new commissions and old favourites at the Royal Albert Hall this season

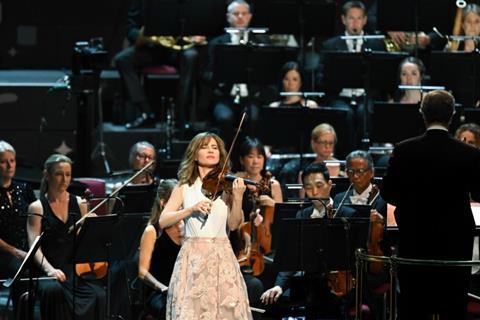

Lisa Batiashvili was partnered by Sakari Oramo on her first recording of the Sibelius Violin Concerto, some 20 years ago, and so there could be no question of mutual unfamiliarity or lack of affinity when they opened the First Night of the BBC Proms with the same piece (18 July). However, their performance served to open out potential points of tension within the concerto itself: between a Paganinian virtuoso style of solo writing and a more experimental orchestral language contemporary with the Third Symphony. The result was not so much a culture clash as an intriguing sense of the concerto’s first movement proceeding in two parallel streams, which drew near in the second, and merged in the polka-finale. Here, Batiashvili took brave risks with sound and phrasing, relinquishing her golden, centred tone from the first movement, digging down to the grainiest depths of her ‘del Gesù’ and bringing back a boisterous folk style alla zingarese, keening with campfire portamentos.

Some sparks from that campfire, however anachronistic, might have fanned the weak flame of inspiration underneath the Concerto in G major op.8 by Joseph Bologne, otherwise known as the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. The motives for reviving his music are sound: not just an eventful life-story, and a vanishingly rare instance of an 18th-century Black musician, but on his day an accomplished composer. This wasn’t one of those days, I would venture, despite the best efforts of Randall Goosby (making his Proms debut) and the Orchestre National de France under Cristian Măcelaru (23 July). The concerto’s 20 minutes felt like double the length (better that they had been half) when the melodic inspiration was so thin and workaday, and yet recycled anyway in a pale simulacrum of Classical style.

Goosby sounded more at home in the luscious French Wagnerisme of Chausson’s Poème. As in the First-Night Prom, there was a perceptible variance of approach, between the spontaneous phrasing and serenely floated colours of Goosby’s playing, and the more sustained legato of Măcelaru’s conducting, but this distinction felt true to the tragic literary narrative behind Chausson’s inspiration.

The Strad Podcast Episode #1: Lisa Batiashvili on the Sibelius Violin Concerto

Read: ’Quality should always be the priority’ - Johannes Moser’s life lessons

In a Proms season strikingly short on string concertos, the only substantial new piece came three weeks later (13 August), when cellist Johannes Moser gave the UK premiere of Before we fall by Anna Thorvaldsdottir, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Eva Ollikainen. An opaque programme-note by the composer yielded no insight into the relevance of the title, or even the form of the piece, which turned out to fall into the conventional tripartite division, with a cadenza linking second and third movements after the fashion of Shostakovich’s First.

On Radio 3, however, the composer remarked: ‘My core inspirational thought was of teetering on the edge… of balancing and finding your feet… There’s a lot of tension, and a balance between distorted energy and deep lyricism, and a search for the roughness in both.’ Moser talks about ‘tectonic sound masses that shift against each other’, which certainly goes for Thorvaldsdottir’s music as a whole, but does not naturally translate to the concerto genre (this is her first attempt), on this evidence, or at least to a sense of its identity as one with or against many, in dialogue or argument.

Moser certainly got a helping hand on the broadcast, whereas in the hall his part suffered from a balance problem, perennial in cello concertos, exacerbated here by solo writing cast in the same dour registers as long strands of the orchestral texture. The prevailing mood of dank and misty weather barely lifted through the course of 27 minutes, except when Moser unleashed a barrage of effects (martélé, sautillé and so on) during the cadenza. For the rest of the time his part reminded me of a climber scrabbling to keep his footing on a steep slope of loose scree, which may be what Thorvaldsdottir had in mind but did not make for rewarding music.

Klaus Mäkelä’s Proms as chief conductor designate of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra had been touted in advance as hot tickets. In the event, Janine Jansen’s account of Prokofiev’s First Concerto (24 August) was the highlight of them, precisely because she brought a sense of direction and personality to music making which was otherwise well-organised but lifeless. Her generous, portamento-led phrasing was supported by a broad and continuous vibrato, perhaps designed to project into the Royal Albert Hall given her more contained and intimate take on the piece in her Decca recording with Mäkelä. Either way, she vividly sketched Prokofiev’s balletic gallery of grotesques, hinting in the Scherzo at a malign spirit which deserved more sharply drawn support.

Read: Isabelle Faust: clarity and insight

Read: Violinist Inmo Yang to make Proms debut on $20 million ‘del Gesù’ violin

As a last-minute stand-in for Hilary Hahn, Isabelle Faust did not thicken her slender, elfin tone for the venue: I have seen her play concertos by Mozart (in 2017), Ligeti (2022) and now Dvořák (26 August) at the Proms, and on each occasion she has made the piece her own while honouring the score. Rather than the often-quoted debt to Brahms, Dvořák’s concertante writing sounded on this occasion a close cousin to his chamber music, not least thanks to the alert accompaniment of Andris Nelsons and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Spreading chords rather than attacking them, bending both intonation and phrase shapes, Faust invited the orchestra to follow suit. Even when operating on a mere thread of tone in the slow movement, her sound always projected, and she never played a clichéd note; the finale gently touched on Dumka style, balancing melancholy and momentum in equal measure. What an artist she is.

Inmo Yang, making his Proms debut on 28 August, got off to a rocky start in Sarasate’s Carmen Fantasy. Drawing a baritonal, viola-like depth of tone from the 1743 ‘Carrodus’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, he consistently played ahead of Marie Jacquot’s beat (directing the BBC Symphony Orchestra). Whether through nerves or under-rehearsal, he struggled to find a specifically operatic character for each episode, at least until the Flower Song, which showed off some luscious sautillé. The pallid elements of his Sarasate were immediately placed in salient context by his encore, the op.6 Recitativo and Caprice by Kreisler. Using a much fuller range of tone and dynamic, Yang showed here some of the imaginative musicianship which makes his DG solo album so rewarding: the technique to paint on a larger canvas will surely come with time.

Peter Quantrill

No comments yet