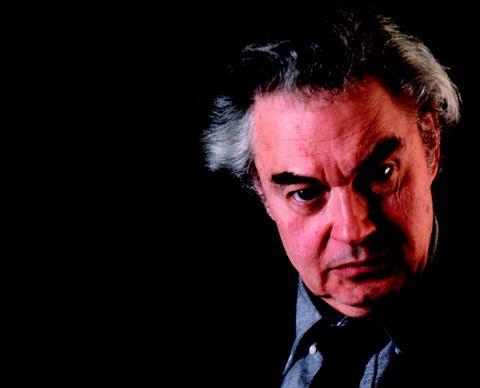

The well-travelled concertmaster discusses his time leading British, Dutch, US and Canadian orchestras as he talks to Julian Haylock

Did you feel instantly at home in an orchestral environment?

Yes, it felt entirely natural. My mother was extremely pragmatic about my musical talent and wasn’t in the least bit stage-struck, so there was no pressure from home to follow a big soloistic career. As far as she was concerned, as long as I enjoyed playing the violin and kept out of trouble, that was fi ne. It helped that I had such an intensive training. Within eight years of graduating from Toronto’s Royal Conservatory, I had already been a member of four excellent orchestras – the Toronto Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony, CBC Symphony and Boyd Neel Chamber Orchestra – and had played under some outstanding conductors, including Victor de Sabata, Leopold Stokowski, Igor Stravinsky and Darius Milhaud.

When you were appointed concertmaster of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO), you were only 25. How did you assert your authority?

Although I was still quite young, I had a calm head on my shoulders and had already learnt that the best way is to lead by stealth. I waited until I felt comfortable in my surroundings, and then began a rotation system. I invited several people to come up and play next to me, so that I really got to know my section and found the ideal desk partner. I think there was a bit of resentment to begin with, but after I played the solos in Sheherazade and chose Paganini no.1 as my fi rst concerto performance, that pretty much sealed the deal. It was a bit of a gamble at the time, but it paid off.

What did you try and change during your three years at the RPO?

London orchestras in general had a lack of carrying power at that time, compared with their American counterparts, so I encouraged the strings to bear down on their instruments a little more and create a bigger sound.

How did you cope with conductors who were less able?

If things got really bad, I would reassure the maestro that I was there to understand him and follow his physical and verbal instructions, but that I couldn’t read his mind. That usually did the trick!

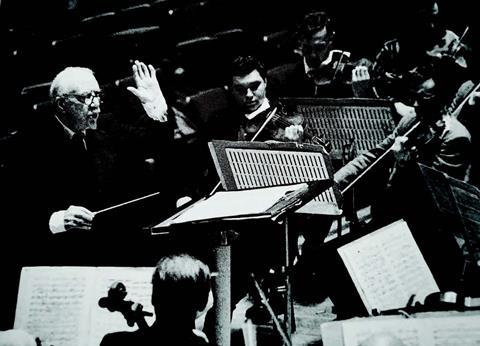

The Concertgebouw Orchestra must have been a very different proposition.

In many ways it was the exact opposite. The strings already produced an incredibly rich and full sound, which was ideal for its bread-and-butter repertoire: Bruckner, Mahler, Brahms and Strauss. In other music I tried to get nearer to the transparency and clarity of the London orchestras – their remarkable pianissimos and flexibility when accompanying. The best way to make your mark with a new orchestra is through your playing, and I was fortunate in that my very first work with them was Bach’s St Matthew Passion, which has one of my favourite solos: ‘Erbarme dich’.

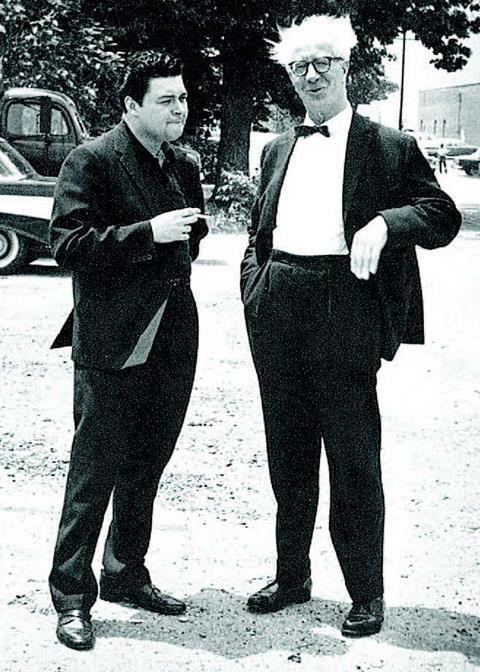

What convinced you to move from Amsterdam to Chicago?

I had already turned down an invitation from Rudolf Kempe to lead the Berlin Philharmonic and was considering a solo career when George Szell virtually twisted my arm to go to Chicago. In the end it turned out to be a good decision because leading a major North American orchestra gave me a very different kind of experience. The Chicago Symphony combined the flexibility and litheness of the RPO with the luxuriant sophistication of the Concertgebouw. The players behaved extremely well during rehearsals and there was a great atmosphere, so there was never any need to impose discipline. They shaped every tiny nuance to the point of perfection. Whatever a conductor wanted, the orchestra could just do it.

Looking back, how did you achieve what you did as a concertmaster?

Apart from my playing ability, I found that it was better not to command but to coerce, which was unusual for that time. Just as orchestras will no longer put up with dictators on the podium, so a concertmaster has to be far more pragmatic – a first among equals. It’s more a case of clever psychology and gaining the respect of your colleagues through example. If there was ever a problem within the section, I invited the individual concerned to come and sit next to me on the front desk for a time. If there was something I couldn’t solve, I would simply take it to the players’ committee and not get involved on a person-to-person basis.

How did you handle auditions?

I preferred hearing candidates play behind a screen, at least initially. I would invite them to start with the fi rst movement of a concerto they had prepared, then we’d move on to some fairly playable orchestral excerpts followed by some virtually unplayable ones, to see how they coped with being put on the spot. It was a very tall order, so it often came down to who was best at what I call ‘honourable faking’.

Did your experiences as an orchestral player shape your teaching?

Definitely. I gave over part of every lesson to looking at orchestral parts and I also used to give classes on orchestral playing. I found that in many schools and colleges the teachers had never played in a professional orchestra, with the result that they tended to look down on it as something beneath them and their students.I gained so much knowledge from working with great conductors and colleagues – it was not a job in the normal sense, but was more like having a series of amazing lessons for which I actually got paid. You learn so much more about music making playing in an orchestra, which as a soloist you tend to miss out on. You see music in an entirely different perspective and not, as I always say, merely through the f-holes of a violin.

TIMELINE

1932

Born in Toronto, Canada

1939—48

Studies with Christopher Dafeff and Eli Spivak at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music

1950—2

Violinist, Toronto Symphony Orchestra

1952—6

Violinist, CBC Symphony Orchestra

1957—60

Concertmaster, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

1960—3

First concertmaster, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; concertmaster, Amsterdam Chamber Orchestra

1963—7

Concertmaster, Chicago Symphony Orchestra

1968—72

Professor, Oberlin College Conservatory of Music

1972—5

Professor, Academy of Music, Vancouver

1982—7

Concertmaster, Toronto Symphony Orchestra

1987—97

Professor, University of Washington; School of Music, Seattle, Washington

1975—87

Professor, Royal Conservatory of Music, Toronto

5 Readers' comments