Cellist Tommy Mesa’s historic Gagliano cello frames an eclectic programme spanning repertoire familiar and new.

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

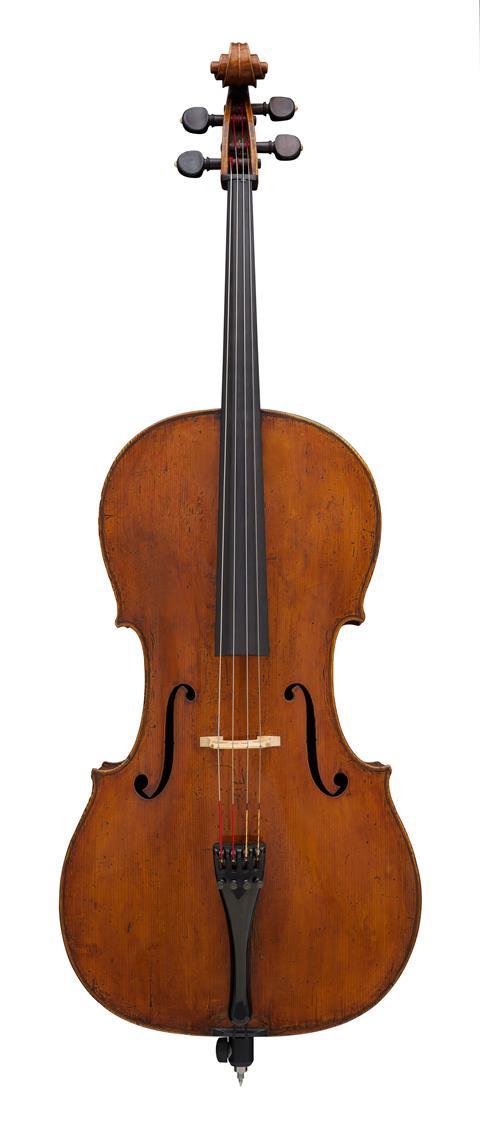

The enigmatic-looking album title 17(67) pairs a fragment of internet slang with the year in which Tommy Mesa’s Nicolò Gagliano cello was made. Recorded with pianist Yoon Lee, the album places that rare instrument in dialogue with music shaped by different eras, traditions and cultural contexts.

A Cuban-American cellist based in New York City, Tommy Mesa is a recipient of Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Career Grant and the Sphinx Organization’s Medal of Excellence. He has built a profile that combines standard repertoire with a strong commitment to newer music – a balance clearly reflected on 17(67), his second solo album (on the Azica label).

The programme moves easily between familiar landmarks like Saint-Saëns’s The Swan and Massenet’s Méditation and works by contemporary composers including Jocelyn Morlock, Marlos Nobre, Andrea Casarrubios, Jennifer Higdon and Kinan Azmeh.

Mesa’s own arrangements of music by Florence Price and Ernesto Lecuona add a particularly personal dimension to the album. Rather than set old against new, 17(67) presents an eclectic programme unified by the sound and history of the instrument itself.

Tommy Mesa spoke with US correspondent Thomas May about designing his time-spanning programme, recording on a historic cello and the artistic relationships that inspired 17(67).

The title 17(67) hinges on a clever numerical double meaning. When did it click for you – was it a conceptual starting point, or something that revealed itself once the repertoire began to settle?

Tommy Mesa: I’d like to think that in 1767 Gagliano somehow knew that ‘67’ would become a trend, so he timed that year perfectly for one of his best instruments. Maybe not! But once I realised the cello was made in 1767, the title clicked immediately – it felt too perfect not to lean into.

17(67) moves from familiar landmarks like Saint-Saëns’s The Swan to far more recent works such as Jocelyn Morlock’s Halcyon and Marlos Nobre’s Poema III. What were your criteria for shaping the programme?

Tommy Mesa: The idea behind the programme was to show that new works we love – like The Swan – can exist beautifully alongside pieces the listener may not know as well. When placed next to each other, they really hold up, which is a beautiful thing. My criteria was simply to choose works that listeners could enjoy and experience for pure enjoyment and relaxation.

You’re recording on a 1767 Nicolò Gagliano – an instrument that’s lived several lifetimes already. Did working so closely with that cello influence not just your sound, but the repertoire you felt it wanted to speak?

Tommy Mesa: It’s safe to say that the cello’s sound didn’t influence the repertoire choices themselves, but it absolutely influenced how I interpreted these works in front of a microphone. My previous cello wasn’t nearly as sophisticated, and with this instrument I felt I could really push the envelope with colour and timbre in every direction.

This cello was made by Nicolò Gagliano, the father of the famous Gagliano family of makers, and is probably the finest example of his work. The condition is beautiful. I can’t be grateful enough to Roger Dubois at Canimex Inc. for loaning it to me. The instrument has raw power and is robust across all registers – I never have issues with balance in concerto settings with full orchestra.

In the recording studio, the more delicate sounds also come effortlessly. With a microphone in front of you, exploration of the lower registers becomes almost infinite in terms of what’s possible. For repertoire on this album that can be highly meditative and reflective, I learnt a great deal about the instrument in the studio, particularly when it came to softer sounds. Projects like this are important for my growth as a musician because they push me to find sounds I love within each composer’s world.

What do the contemporary works you’ve chosen reveal about the so-called ‘classics’ when they’re heard side by side?

Tommy Mesa: I sometimes like to play devil’s advocate and ask what actually makes a ‘classic’ a classic. A work like Massenet’s Méditation persists for many reasons – we value it for its inherent beauty and for its context within Thaïs, and rightly so. But Marlos Nobre’s Poema and Jocelyn Morlock’s Halcyon are also inherently beautiful. What makes them less famous? Often it isn’t the value of the music itself.

Society elevates certain works for many reasons – usually good ones – but my goal is to elevate pieces that are equally beautiful and worth hearing, even without centuries of history behind them.

You’ve included your own arrangements of Florence Price and Ernesto Lecuona. What kind of relationship do you feel you need with a composer before you’re willing to step into the role of arranger?

Tommy Mesa: Ernesto Lecuona is perhaps the most famous Cuban composer, and his music feels very close to my heart as a first-generation Cuban American. After this album’s release, I’ll be working on another project titled American Immigrant, which will feature commissions for cello and piano by composers with their own immigrant stories. My father was born in Cuba and came to Miami with his family to start a plumbing company from scratch, and those roots feel very special to me.

La Comparsa is meant to sound like a carnival approaching from afar, growing louder as it comes closer before disappearing into the distance. I love programming Lecuona’s music because many listeners haven’t heard it, and certainly haven’t heard these arrangements for cello and piano. Being able to share that part of my heritage feels important to me.

Florence Price has also been on my radar for some time. Her music is gorgeous, and we’re witnessing a real renaissance in the rediscovery of her work. Deserted Garden translates beautifully to cello and piano, partly because it was originally written for the lower register of the violin, which suits the cello perfectly. Its depth of feeling and blues-inflected harmonies allow us to appreciate African American idioms within a Western classical framework. It’s emotional, stirring and deeply felt.

Pianist Yoon Lee is a constant presence throughout the album, even as the musical languages shift dramatically. How did the two of you negotiate balance, colour and character when moving between centuries – rehearsal-room debates, or instinctive chemistry?

Tommy Mesa: Yoon Lee has been one of my collaborators for several years, and I’m incredibly grateful to her for being such a strong presence on this album. Honestly, the collaboration here was very straightforward and easy. We had ideas, we shared them, and we were always on the same page.

I’d love to make up a story about us getting into a fistfight over a tempo marking – but since we’re friends, the entire process was an absolute pleasure.

Read: Cellist Tommy Mesa joins Manhattan School of Music faculty

Watch: Tommy Mesa performs Saint-Saëns: Cello Concerto No. 1

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet