How the composer and violinist overcame prejudices of the day and logistical challenges to premiere a new violin concerto successfully

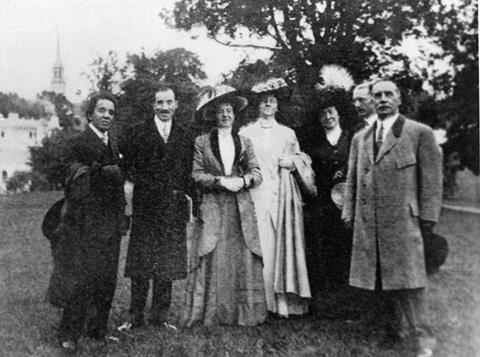

Courtesy Maud Powell Society

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (far left) at the Norfolk Festival in 1910 pictured with (left to right) tenor George Hamlin, Maud Powell, Mrs Arthur Mees, Gertrude Stein, pianist Franklin Bassett and conductor Dr Arthur Mees. Photo by H Godfrey Turner

The following extract is from The Strad’s March 2022 issue feature ‘Coleridge-Taylor violin and chamber music: From fame to footnote’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The March 2022 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

Tours to the US gave Coleridge-Taylor a chance to become reacquainted with the American violin pioneer Maud Powell, whose influence was pivotal in the development of violin playing in North America. They first met in November 1898 at Powell’s London debut, when she performed his Gipsy Suite. She included the work in her American recitals in 1901, thus introducing his violin music to the American public. In fact, it is mainly thanks to her that his music has survived through the years.

Interestingly, their stories are similar inasmuch as they both succeeded in the face of extraordinary prejudices – he against black musicians, she against professional female violinists. Also, they were both committed advocates of racial equality and shared a passion for the violin and music of different cultures. Indeed, they played a significant part in the integration of African music and musicians into the emerging American tradition of art music.

Powell bolstered the composer’s efforts to change the perception of African spirituals as having dehumanising qualities and to make them better known to the general public. She was responsible for the violin transcriptions of his original piano works, including Deep River from his groundbreaking set of 24 Negro Melodies op.59 (published 1905). Powell performed that arrangement during her recital at Carnegie Hall in October 1911. In fact, this was the first time in history that a white, classically trained artist had played a spiritual in a concert hall, as previously only primarily black ensembles such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers and artists like Henry Thacker Burleigh, Clarence Cameron White and John Rosamond Johnson had presented them.

Read: My violin heroine Maud Powell, by Rachel Barton Pine

Read: Pioneering Female String Players from The Strad archives

The American critic and musicologist Henry Edward Krehbiel hailed Powell’s transcription as ‘the most effective bit of music based on American folk song which has yet been offered to the public’. Importantly, she had the artistic courage to be the first to record Deep River (for the Victor Company, 15 June 1911), thus helping it gain worldwide popularity. This popularity endured, with the work going on to be performed by many concert artists (both black and white), and new arrangements of the spiritual being made by the likes of Jascha Heifetz.

Among Coleridge-Taylor’s larger-scale works for violin and orchestra – such as his gloomy yet virtuosic Ballade in D minor op.4, his Legende op.14 (1893) and his Romance in G major op.39 (1899) – is the Violin Concerto in G minor op.80, dedicated to Powell and conceived in 1910 during the prestigious Norfolk Festival, Connecticut, where Coleridge-Taylor had been appointed to conduct the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in the complete Song of Hiawatha op.30 and the premiere of his ‘rhapsodic dance’ The Bamboula op.75 (1910). He was the first black conductor to direct the then exclusively white orchestra, his programme preceded by Fritz Kreisler performing Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole.

The concerto could be seen as a personal story written for a friend – in fact, Powell playfully claimed that it was ‘Taylor-made’ for her. Having in 1911 refused to pay $1,000 to the publishers Novello for the privilege of giving the US premiere of the Elgar Violin Concerto (because she didn’t think it was worth it), Powell – who had previously introduced American audiences to major concertos such as those by Bruch, Dvořák, Lalo, Saint-Saëns, Sibelius and Tchaikovsky – instead gave the money to Coleridge-Taylor.

’The Coleridge-Taylor work is fascinating, if not great music. It contains interesting melodic material and piquant rhythms, and it is gratefully written for the solo instrument. Miss Powell played it with all the consummate artistry of which she is mistress’

The work’s eventful history encompassed a number of anxiety-inducing misfortunes that befell the manuscript itself. First, the premiere was almost postponed as the full score and orchestral parts sank with the Titanic and had to be recopied post-haste. Secondly, the return journey of the score and orchestral parts was delayed owing to mislabelling with the incorrect address, causing great anxiety to Coleridge-Taylor as the British premiere was confirmed for October 1912 and the parts were due to arrive in England some time in September.

Despite all the tensions and pressures, the US premiere was a success. A critic from Musical America of 15 June 1912, commented: ‘The Coleridge-Taylor work is fascinating, if not great music. It contains interesting melodic material and piquant rhythms, and it is gratefully written for the solo instrument. Miss Powell played it with all the consummate artistry of which she is mistress.’

Read: Coleridge-Taylor violin and chamber music: From fame to footnote

Read: Joseph White: Making history

Read: ‘We have to fight a history of stereotyping’ - Black representation in classical music

-

This article was published in the March 2022 Leonidas Kavakos issue

The Greek violinist tells Charlotte Smith why his recording of Bach’s Solo Sonatas and Partitas is a culmination of a three-decade journey. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Leonidas Kavakos

- Conductorless Orchestras

- Early Lutherie Experience

- Laura van der Heijden

- Luigi Cavallini

- Coleridge-Taylor Violin and Chamber Music

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet