The First Violin Concerto by Shostakovich brings back memories of the Russian violinist’s first meeting with Mstislav Rostropovich – an encounter that blossomed into firm friendship

Maxim Vengerov © Uwe Arens

In 1994, when I was 19 years old, I was ridiculously busy. I was performing 130 concerts per year, and when I wasn’t travelling I’d want to spend the time relaxing with my family. That left very little time for learning new repertoire, but when the opportunity came up to perform and record Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto no.1 with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Mstislav Rostropovich, of course I agreed. Although I’d never studied it, I’d fallen in love with the concerto years before. I only had one condition: that I got to meet Rostropovich beforehand. Slava had had such a deep relationship with Shostakovich, I felt that it could be a direct link to the composer himself.

I met him at the Evian Festival in Geneva, where he was the artistic director. When he saw me he threw his arms wide as if he was greeting an old friend. And the first thing we did together was feed his dogs! They were both tiny and he looked after them as if they were the most important things in the world. He had such humility as well as an obvious passion for life; when we went out to dinner together he insisted on meeting the chef at the end, and kissing him five or six times. There was that human element in his stories about Shostakovich. Once the composer phoned him, aged 19, at 3am asking him to come over urgently. When he arrived, Shostakovich poured them both a glass of vodka and thanked him profusely for his company – he wanted to share his inner emotions with another soul, and couldn’t bear ten minutes alone. That meeting in Geneva was the start of a long relationship: I knew Slava for 17 years and he became a great mentor to me. Near the end of his time he said I was ‘the last flower in my life’.

So then I had to learn the concerto. I think it’s the one I spent the least amount of time practising – I had four days before the first rehearsal with the LSO and I managed to do it in time. Slava had lots of advice that he’d always convey in visual terms rather than through technical details: ‘You’re playing the fourth-movement Burlesque as if it’s the Mendelssohn Concerto. Play it as if you’re watching a fire in a public house with all the chaos and panic going on around you.’

Before the LSO rehearsal I played the concerto for Slava at his apartment in London. When it came to the third-movement Passacaglia, he said ‘now go on to the fourth’, but I could tell he wasn’t happy with it. So I pressed him and he explained: ‘It’s so difficult for a young man like yourself to understand all the horrors Shostakovich went through.’ I knew what he was saying, and said: ‘I can try my best, but with the recording coming up so soon, how can I change it?’ He told me just to look into his eyes and play what I saw. I barely slept the night before, as I had no idea how I was going to play it. But when it came to that movement, I looked into his face and saw everything I needed – it was like reading a script or an autocue. I don’t remember how I played, but then when I listened back to it, I had the strange feeling I was listening to someone else playing. It’s the only time in my life that that’s happened, when somehow my emotions blended with Slava’s.

I once asked Slava if I could say something really stupid: ‘As much as I love the Beethoven Concerto, the Shostakovich has more dimensions, as if it’s more developed.’ He said ‘You’re absolutely right – it’s a new language, another step in the development of the violin repertoire. It’s a concerto that has everything, most importantly in the Passacaglia.’ It’s something I couldn’t understand immediately, and it’s grown with me my whole life, along with the totally different way I now interpret and play the piece.

-

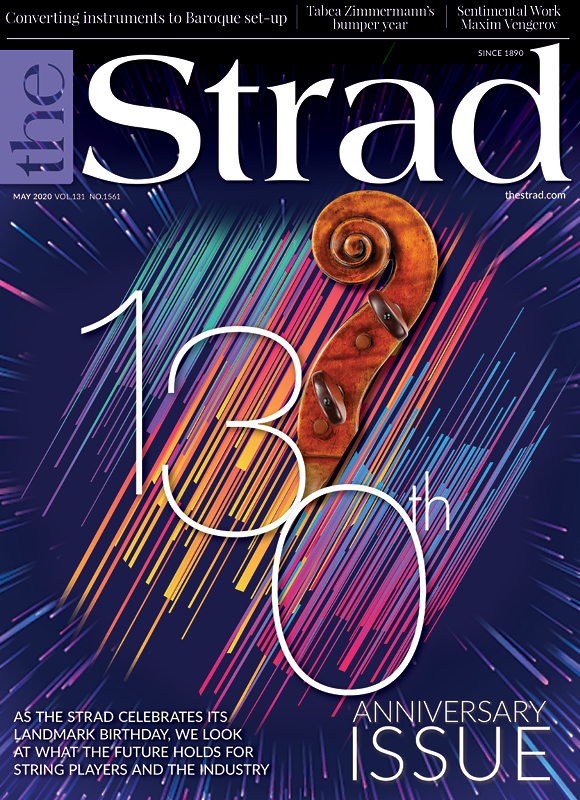

This article was published in the May 2020 130th Anniversary issue

The Strad marks its 130th anniversary with a look at the future of string playing and the violin industry. Explore all the articles in this issue.

More from this issue…

- A look at the future of string playing and the industry

- Violist Tabea Zimmermann on her bumper year

- Converting an instrument to Baroque set-up

- Making a career in music therapy

- How luthiers can avoid repetitive strain injury

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet