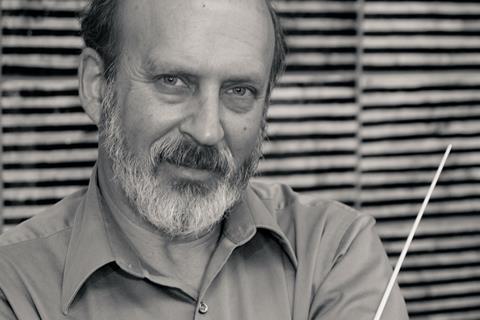

For musicians hoping to build up their confidence and establish a career, competitions can be more of a hindrance than a help - argues the orchestral violinist and author Gerald Elias

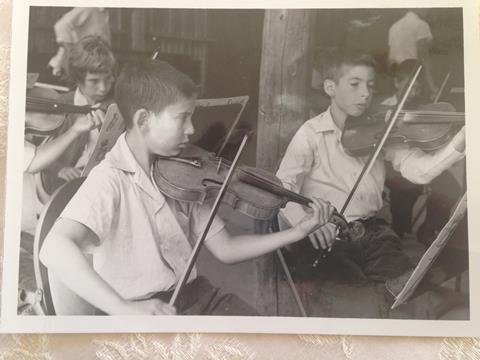

I entered a New York-area violin competition when I was a sophomore in high school. It was so long ago I don’t even recall which one it was. All I can remember is that one of the judges, perhaps the only judge, was the highly-esteemed cellist, Benar Heifetz. I had worked for months on the Suite in A Minor by Christian Sinding with my teachers Amadeo Liva and Ivan Galamian. Anyone who has heard the Jascha Heifetz recording of the suite knows what a lyrical and technically dazzling concert piece it is, an ideal showcase for a young violinist.

My stepmother schlepped me to many a rehearsal at the home of my pianist on Long Island, whose name I can’t remember, either. At the time she seemed elderly, but in retrospect I’m guessing she was probably only in her forties. She was quite a good accompanist, well-trained to adjust flexibly to nuance and subtle tempo changes. She also provided me, a teenage musician, with moral support. More about that later. By the time the competition rolled around, I felt technically and musically secure.

I sailed through the audition. When I finished playing, I went to the adjoining room to pack my violin away, daring to hope I had a reasonable shot to be one of the prize winners. Through the wall I heard the next contestant, a violinist a few years older than me, begin a mesmerizing piece I had never heard before, which I was later told was the Ballade by Eugène Ysaÿe. Within thirty seconds, I realized I had no chance winning anything in that competition. I was simply not in that class.

Over the next fifty years, I lost more competitions and auditions than I care to remember. On a few occasions, though, the gods were with me. The two most meaningful wins were for the Boston Symphony violin section (on the fourth try) upon graduating from Yale University, and for associate concertmaster of the Utah Symphony thirteen years later. If not for having won those two, I would probably have spent my life dwelling on all those that got away. The fact that, a half-century later, I still feel a twinge of pain and humiliation from that high school experience speaks volumes about the inherent psychological impact of competitions. But I’ll also never forget the one positive learning moment from that audition.

Read: Violist Tabea Zimmermann on the pressure of competitions

Read: Are competitions inherently problematic?

It had somehow become evident—body language, subtle hints—to my Sinding accompanist that there was a certain level of tension between my stepmother and me about the very notion of entering the competition. As much as I enjoyed playing the violin in those days, I gravitated toward orchestral and chamber music and shrank from solo performances. I recall one long-ago Thanksgiving when, asked by my parents to perform for the assembled guests, I locked myself in my bedroom. Competitions were worse. Being examined under a microscope generated deep-seated anxiety as opposed to joy, creating the exact opposite result of what I supposed playing music should be doing.

What my parents were thinking, though totally well-intentioned, was something quite different. What they were considering was that by entering competitions I would receive the recognition they believed I deserved, which could result in greater opportunities, and perhaps even substantial prize money and scholarships. With their limited means, and considering the cost of putting my two older siblings through college and my lessons with Mr. Galamian (in those days a whopping $25 per hour), it was an understandable point of view and I felt the obligation to succeed by winning. Nevertheless, like a recalcitrant horse with a restraining bit in its mouth, I chafed at being forced in a direction that didn’t suit me. At the end of one of the rehearsals, my accompanist must have sensed this. In the presence of my stepmother, she said to me with the kindest of smiles, ‘Jerry, you don’t need to play the violin for anyone else. Only do it for yourself.’ If there was any good to have come from that competition it was those words. ‘You don’t need to play the violin for anyone else. Only do it for yourself.’

I was fortunate. In my youth, music was only one of many interests, so after losing the competition it was relatively easy to dust off my ego and move on. I can now say, that it is a pleasure for me to play for anyone at any time. I survived the gauntlet. For others, who from infancy are funneled into a narrow performance track, it isn’t always so easy.

Here are some other thought-provoking words. These from a former colleague who requested anonymity and whose experience with a competition-minded parent is a variation on a theme heard all too often:

‘I was one of those little kids made to practise hard every day at a young age, many tears and scolding and even beatings. I remember that one time my father pulled me out of bed at 10 p.m. to play for him, my tears streaming down my cheeks under the moon. He said, ‘Mozart’s father pulled him out of bed at 12:00, I only got you up at 10:00.’ Luckily, I got into music conservatory at the age of nine. It was tense study but not as tense as it was at home. Not a childhood that I would recommend to anyone! I learned to love music later in my life. I was lucky that way!‘

Where, and for whom, is the value in competitions? Who are the interested parties? The audience, the judges, the teachers, and, of course, the contestants. Let’s take a look at each, one at a time.

What can be more exciting or more heartwarming for a music lover than to sit in an audience and witness dozens of young pianists or violinists or singers progress over the course of two to three weeks, as the winnowing process sorts out the ‘prodigiously gifted‘ wheat from the ‘merely talented‘ chaff? If only all young people were like these, the audience dreamily muses, wouldn’t the world be a wonderful place? Let’s give these hard-working, dedicated youths our full support. And maybe someday, twenty or thirty years down the line when so-and-so has attained international stardom, an audience member can look back with pride and say, to the great envy of his friends, ‘Yes, and I was in the audience when so-and-so won the Grand Prix du Timbuktu.‘ And, not to be overlooked, being in the audience one does hear some beautiful music.

Sitting on a panel of judges is an honour. It’s a feather in one’s cap, though being selected for it sometimes seems to be the result of networking virtuosity as much as musical virtuosity. Being a judge is recognition that one’s opinion has attained a certain level of broad respect and gravitas, which can’t hurt one’s ability to pursue one’s own performance career or snare the best students. Ostensibly impartial, judges for major international competitions are compensated with business class travel, rooms in four- or five-star hotels, and five-figure fees. (I was unable to find specific data for these claims, but relied on anecdotal information provided by a trusted colleague, well-known in the violin world. I welcome precise data if it’s not accurate.)

Read: ‘It’s the taking part that counts’: Are competitions always defined by results?

From the judges we logically proceed to the teachers, as on occasion they can be one and the same. What’s in it for the teachers? That’s pretty clear. A prize-winning student generates a great deal of well-deserved pride, and enhances the teacher’s reputation. As such, the victorious student also becomes a highly effective marketing tool. If one out of ten of your students hits the jackpot, the other nine don’t need to enter the equation. Your stock skyrockets, and the more students you can crank out to enter the hundreds of available competitions the more likely you can get even better students, build your studio and your reputation, and, not to get overly down-and-dirty, charge more money for lessons. Teaching is a living. It’s a job as much as it is a calling. One needs to pay the mortgage.

Things get tricky when the teachers are also the judges, and we’ll get to that in a moment, but first let’s talk about the dueling contestants themselves.

On the plus side, there’s no doubt that in preparing for a competition there is a heightened intensity to one’s practice. You have several months to perfect hours of repertoire—everything from sonatas to concert pieces to concertos—for all of the several rounds of competition in which you hope to be included. Every note will be scrutinized. Every gesture. Every phrase. Every nuance. Chances are, it is the most concentrated practicing one ever does. The hard work and discipline can go a long way to informing one’s practice habits and, indeed, can raise the overall level of one’s ability. Even before the actual competition, there can be a sense of having achieved something quite remarkable. And for the winners of the bigger contests, that sense can become a reality, with enough performance opportunities to begin a career.

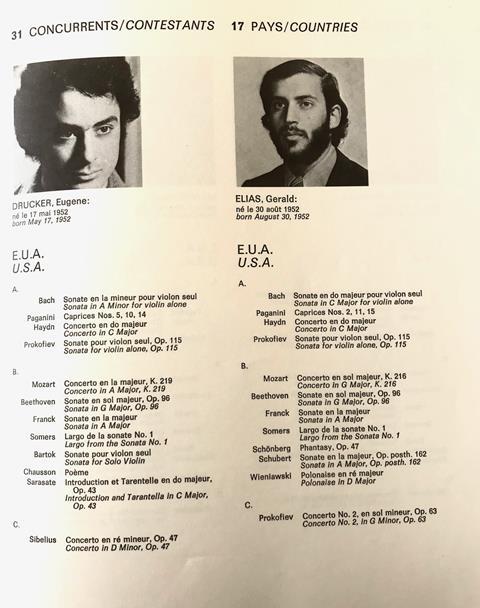

The drawback, however, is that, except for a competition’s few winners, there is little positive to be taken away. Even a second or third place finish has little more enduring value than a bridesmaid’s bouquet. In 1975, while a student of Joseph Silverstein, I participated in the Montreal International Violin Competition. Six months of intense practice went down in flames in five seconds of the first round when my fingers got twisted in knots in a particularly gnarly passage in the Paganini Caprice No. 2. Nothing to be ashamed of. It happens to everyone. It just happened to me at the worst time. I was out of the competition. There were compensations, however. For two weeks, I was hosted by a lovely and hospitable French Canadian family. They treated to me to incredible food and to a Montreal Expos baseball game, which I wouldn’t have been able to attend if I had advanced to the second round, which one of my good friends had the bad luck to have to endure before he, too, was eliminated.

So life does go on, but we should also note the economics of being a contestant because it is a major investment of money as well as of time and effort. As reported by the renowned violinist, Rachel Barton Pine, herself a major competition winner, ‘Competitions are expensive. You’ll need to find an accompanist and pay that person’s hourly rate for rehearsals, plus their competition fee. You may also have to pay gas and parking money. If you know any of the other competitors, you may be able to reduce everyone’s costs by using the same accompanist. If you do so, you should probably ask the competition organizers to schedule your auditions close together. Most competitions charge entry fees, and some require pre-screening tapes, which can be expensive to produce. Also factor in that your some of your presumably-expensive violin lesson may be devoted towards preparing for the competition. Since most competitions have dozens of entrants but only a few prizes, your chances of winning are slim, even if you play very well. You could spend hundreds of dollars each season on competitions, win a few, and still not break even.‘ [Violinist.com, June 12, 2007] And, if you include plane fare, thousands of dollars.

I almost left out one of the essential participating demographics, maybe because you usually don’t see them: the competition organizers. Music competitions are a business, and the people who organize them make money. And why not? It’s their job. People have to be paid: venue providers, program producers, piano tuners, sound and lighting technicians, travel and lodging companies. The list goes on. Everyone gets a piece of the revenue pie. Everyone except the dozens of young musicians who provided the raison d’être and who were not among the three or four prizewinners. What do they have to take home to compensate them for six months of grueling preparation and draining their savings? The honour? The glory? The experience? Is that adequate compensation?

There’s nothing intrinsically bad about competitions being a business, but it needs to be stated that’s what it is. And the proof is in the pudding: ‘Only five international piano competitions were held in 1945, rising to 114 by 1990, and now, by the count of the Alink-Argerich Foundation, a music information center based in The Hague, about 750 competitions are in existence, of which about 350 were staged last year alone.‘ [New York Times, Aug. 7, 2009] It would be disingenuous to believe this explosive growth was the result either of a sudden outpouring of altruism or of an exponential increase in the number of talented young pianists. It is, in fact, big business. Jacques Marquis is the chief executive of the Van Cliburn Competition, held every four years. ‘As Marquis has added a junior competition and included an additional symphony round in the amateur competition in 2016, the Cliburn’s budget has grown by 50 percent. The budget was about $11 million over the four years leading to the 2013 competition. Marquis said the budget from 2013 to 2017 is about $16.5 million.‘ [Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 3, 2017]

But shouldn’t there be a way to showcase young talent? To provide opportunity? To open the doors to a career in music for the most gifted? There would be few who would not answer yes to those questions. The danger is in not recognizing the fine line between nurturing and exploitation. When there is a combination of competition and youth, whether it is in sports, in beauty pageants, or in music, that danger always exists. It becomes especially explosive when the judges are also the teachers, and opportunism and fraud become rampant. In an extensive article in The Guardian [July 25, 2014], Julian Lloyd Weber details how ‘classical music competitions are rife with corruption and bribery.‘ In the same article, in regard to the ninth Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition, ‘James Gibb, a British juror, told of being approached by a contestant’s uncle who handed him a sealed envelope. In it, he found $1,000 (£588), which he returned. Gibb later discovered that other jurors had given the contestant piano lessons but his suggestion the pianist be disqualified was rejected.‘

One line of defense of proponents of competitions is to accuse those who would be critical of the process of sour grapes. To suggest that those who do not get the outcome they hoped for are, in such a subjective field, simply being sore losers. Yet, in defending themselves thus, they hit upon the crux of the problem.

How does one judge music? It is an absurdity. There is no quantitative way to do that. There is no finish line. There is no time clock to indicate, yes, you are the winner. There are no balls to put in the net, through the hoop, or over the goal line. It is all based on individual taste and style, qualities that are ever-changing and never unanimous (and shouldn’t be). In 2012, Barry Schiffman, artistic director of the Banff Summer Music Programs and Executive Director of the Banff International String Quartet Competition, admitted, ‘There are no perfect results; you have to know going in that it’s an imperfect process. In some ways the idea of a classical music competition is absurd; it’s so subjective. But it attracts interest to the art form, and gives a huge shot in the arm to the emerging artist. I guess I’d say, ‘Do no harm’—whether a person wins or loses, he or she should have a positive experience.‘ [Musical America Special Reports, May 2012] Has there ever been a better example of damned with faint praise? It’s also worth mentioning that in that report, there is a section entitled, ‘Winners Tell Their Stories.‘ Winners. It would have been interesting and instructive to hear from the other ninety-nine percent.

The sad part is that, in preparing for competitions, many young musicians feel compelled to make the ultimate artistic compromise: They try to play in a way that will please everybody equally, and in so doing sacrifice their own musical individuality and integrity.

Even if it could be objectively determined who was the best contestant in a competition, does that necessarily mean he or she is going to be the greatest concert artist? Closing in on a half-century of experience as an orchestral musician, I can tell you that some violinists—either by training or instinct—are born competitors. With single-minded intensity, nothing throws them off. Every note is prepared with absolutely precision, stylistically validity, and unshakeable confidence. They win virtually every audition they take. Yet they are not necessarily the best musicians or, even more telling, particularly good ensemble players. That might lack creativity and flexibility. They might be unable to interpret a conductor’s gestures or verbal directions. They might not be able to aurally dissect dense Mahlerian orchestrations and understand how to fit in. That’s one reason orchestras prudently require probationary periods of up to two years. When it comes to solo performance, some musicians are at their glorious best when they have an hour-and-a-half recital in which to express themselves freely, but will freeze up when, in a competition, they know that every note will be scrutinized under a microscope.

But the fact is, in music there is no way to objectively judge what is best. Music is, by its very nature, subjective. Yes, it appeals to the intellect, but the goal of a composer is not to create an acoustical puzzle; rather, it is to arouse a visceral response from the listener. Yes, hearts and minds, but first come the hearts. So, when one considers the diversity of repertoire required in round after round of concerto competitions, it defies logic to presume there is any way to make an objective, hair-splitting determination of comparable ability. As a case in point, consider the music of Bach and the vast spectrum of interpretations—from performing on period instruments with little or no vibrato and a half-tone lower than contemporary practice, to the lush, 20th-century, quasi-Romantic style of a Heifetz or a Szeryng. Who is to say one is ‘better‘ than the other?

Read: ‘Taking part in competitions improved my playing tremendously,’ says violinist Ray Chen

Read: Do violin making competitions stifle originality in favour of perfection

If there were an ideal world of competitions, in which every judge would be impartial and objective, one would assume the winner was the candidate who performed the best, and that that person would go on to have the most successful career. Yet, in an exhaustive study of several Queen Elizabeth of Belgium piano competitions, it was determined that, astoundingly, the quality of the contestants’ playing was a less significant factor in the outcome than the order in which the contestants performed. [Expert Opinion and Compensation: Evidence from a Musical Competition by Victor A. Ginsburgh and Jan C. van Ours, September 2002] ‘We find that the order and timing of appearance at the competition are good predictors of the final ranking. Since these are randomly set before the competition starts, they cannot affect later success. Because of this, order and timing are unique instrumental variables for the final ranking, which we consistently find to have a significant impact on later success, irrespective of the finalists’ true quality.‘ And further, ‘the conclusion that it pays to do well in the competition is strongly supported by the data. However, the fact that judges’ rankings are affected by order and timing of appearance in a competition needs to be stressed, and sheds some doubt on their ability to cast fully objective judgments.‘ In other words, simply by pulling a bad draw, the deck is stacked against you even before you’ve played a note, diminishing not only your chance of winning but of the prospects of having a successful career.

Given that it is literally impossible to be objective and that the judges themselves can’t even agree on musical issues, why bother making such judgements at all? Why be forced to make a determination that Candidate A is better than Candidate B? In reality, doesn’t that say more about the human species than it does about the candidates or the music? What it seems to say is that our DNA requires us to create a pecking order even when one needn’t exist; for some reason we need to pick winners, giving scant consideration to losers.

So, what is the solution? Is there a solution? How does one separate ancillary vested interests and still maintain the purported, laudable goal of enabling young people to pursue their artistic dreams, and to accomplish that without reinventing the wheel and dismantling the whole system. Here is one possibility, an idea spawned by the exigencies of our current novel coronavirus pandemic:

Just as auto plants have recently been reconfigured to manufacture personal protective equipment for hospital workers instead of car parts, music competitions should be reconfigured into music festivals. Keep the organization and its infrastructure intact. Keep the dedicated, hard-working staff and judges and supportive business coalitions. But change the assembly line. Rather than squirt out three prizewinners from an ever-narrowing tube while letting all the other contestants lick their emotional wounds, perhaps for the rest of their lives (and perhaps hating music in the process), send every one of the contestants into the world as confident, joyful missionaries.

Allow any violinist, let’s say under age twenty-one, the eligibility to submit a recording of their playing. Allow the candidates unrestricted choice of repertoire, encouraging them to perform whatever repertoire they feel they play the best. A panel of judges (yes, we would need them here) listens to the recordings without knowing who the candidates are. In a 180° turnaround from the recent practice of requiring video recording, the recording would be audio only, so as not to prejudice the panel. (The requirement for video recordings is to ensure that there is no cheating; that the listed candidate is the one actually playing. However, since we’re now talking about a format which is not a contest, in which there is no tiered prize money, the incentive to cheat is significantly diminished.)

From all the submissions, the panel selects the top two dozen, more or less, all of whom are invited to a one- or two-week festival at which they’re invited to perform a solo recital, perhaps some chamber music with other participants, and, if logistically possible, a concerto with an orchestra. If the festival is in a city with a symphony orchestra, the two organizations could promote the festival jointly—win-win. If the festival takes place during the summer, the organization could collaborate with any number of summer music festivals. Again, win-win.

Unlike competitions, where there are three or four rounds of increasingly challenging repertoire, the performers would have absolutely free reign to play whatever music moves them the most. Chances are, relieved of the stress of trying to avoid elimination and from performing music they’re not comfortable with, the rewards for the audiences would be that much greater.

Read: István Várdai on winning competitions and beyond

Read: Do violin competitions face extinction?

At the end of the festival, the performers are awarded scholarships, not prizes, which are shared equally from whatever money was raised through donations and ticket sales. Concert managers in attendance could then sign up the ones they liked the most for their artist roster.

End of story. What is lost here? Nothing. The best of the best will still be recognized. Even perhaps more effectively, as, without the beside-the-point pressure to win the big prize or to compromise one’s artistic integrity in the process of seeking it, the truly great artist will be more readily revealed. What is the biggest gain? The joy of playing and listening music becomes the primary focus, not a means to a dubious end. And isn’t joy what music should be about? Isn’t that why we listen to Mozart and Bach? ‘Freude, schöner Götterfunken,‘ Beethoven said about music in his ninth symphony. ‘Joy, beautiful spark of divinity.‘

When my students have asked me about entering competitions, I don’t insist one way or the other, but let them make the decision for themselves. However, I’ve always counseled them, ‘musicians should play with each other, not against each other.‘ The legendary Hungarian composer, Bela Bartok, put it somewhat more poetically: ‘Competitions should be for horses, not musicians.‘

Gerald Elias, a former violinist with the Boston Symphony and associate concertmaster of the Utah Symphony, has been music director of the Vivaldi by Candlelight chamber music series since 2004. He is also an author, and his prize-winning Daniel Jacobus mystery series takes place in the dark corners of the classical music world. His memoir, Symphonies & Scorpions: An International Concert Tour as an Instrument of International Diplomacy, includes the essay, War & Peace. And Music, the basis of his TEDxSaltLakeCity2019 presentation about the potential of music to create a more peaceful world.

![[1] Tae-Yeon Kim pc Marta Ankiersztejn - National Institute of Music and Dance](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/5/9/7/34597_1taeyeonkimpcmartaankiersztejnnationalinstituteofmusicanddance_41722.jpg)

![[1] Javus Quartet pc Victoria Nazarova](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/2/1/2/34212_1javusquartetpcvictorianazarova_822675.jpeg)

![[3] Soyoung Yoon pc Julia Wesel](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/7/7/0/33770_3soyoungyoonpcjuliawesel_221630.jpg)

2 Readers' comments