Our August 2021 issue features the bow making legacy of the Herrmann family in Markneukirchen. In this extract from April 2011, Arian Sheets describes the rise and fall of factory violin making in the 20th century in the same city

The factory’s machines were not the first designed to carve violins, but they were the quickest at the time

MUSICAL INSTRUMENT MUSEUM MARKNEUKIRCHEN

This is an extract from an article that appeared in April 2011: ’Markneukirchen: The rise and fall of Germany’s first violin factory’. To read the full article, click here

A toolmaker named William Thau initiated the process of patenting a machine for carving violin tops and backs. Two different versions of the machine were patented in Germany in 1904. The second version was also patented in France, Austria–Hungary and the US. Thau himself was the proprietor of Julius Berthold & Co., a tool- and machine-making factory in Klingenthal, near Markneukirchen.

His machine was not the first used to carve violins, but it was certainly the quickest of its time. It employed a drum to mount eight pieces of work, which were rotated at the same rate as a cylinder mounted with patterns. As the drum turned, a cutter (turning at 6000rpm) travelled along a screw, making the same cut on each of the eight pieces.

This invention was the basis of the Aktiengesellschaft für Geigenindustrie (Corporation for Violin Industry), founded in 1906. The factory began with 25 shareholders. The largest stake belonging to Thau, who received his share in exchange for the rights to his patent. He was, of course, also the manufacturer of the violin carving machines. Due to the higher wages in Markneukirchen, the founders of the Aktiengesellschaft could never compete with the Schönbach handworkers using the same, labour-intensive methods. Instead, they applied their superior business knowledge, technical expertise and capital to ensure that their higher-paid workers could out-produce the Bohemian handworkers by employing the machinery of mass-production.

The Aktiengesellschaft factory, completed in 1907, was equipped with Thau’s carving machines, as well as a showroom, an extensive wood supply, a saw mill, iron rib forms that could be used to assist in the quick assembly of violin bodies, and carving machines to produce violin blocks, linings and scrolls. Although the violins were roughly shaped by machines, they still had to be finished and assembled by hand. An expert violin maker, Robert Penzel, was employed to oversee the workers and control the quality of the products. The factory’s first unfinished violin bodies and components arrived on the market in October 1907.

The question remained, however, as to whether the notoriously conservative Markneukirchen trade would accept the newfangled machine-made violins. These instruments were in stark contrast to those being produced in Schönbach. To say that the cheapest instruments from Schönbach were old-fashioned would be an understatement. The traditional violin making of the region still employed building techniques and features of 16th- and 17th-century northern European violins, preserved in an area where few workers had the means to travel far from home, and hence built instruments just as they had for generations. The instruments were assembled freehand rather than around a mould in the Cremonese fashion.

Due to this method, they did not require corner blocks; in the cheapest instruments, the blocks were either left out entirely, or faked with thin pieces of wood glued over the insides of the corners to look like blocks but serving no structural purpose. The upper blocks of the instruments, which in classical construction would have been of spruce or willow, were simply carved from the maple of the neck and secured with spruce shims.

The front of a handmade Schönbach violin shows how the bass-bar has been carved out

NATIONAL MUSIC MUSEUM, THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH DAKOTA, VERMILLION

The instruments often did not have glued bass-bars, but instead small bass-bars roughly carved from the wood of the top. They were generally of poor quality, but could be sold at ridiculously low prices to people whose means dictated that their only other choice was to try to make their own. The 1902 Sears Roebuck catalog offered a Schönbach Stradivari-model violin for just $2.45, and Boston wholesaler G.W. Stratton offered violins for as little as $16.00 per dozen in 1883.

Read: Markneukirchen: The rise and fall of Germany’s first violin factory

Read: Markneukirchen merging: linking the Herrmann and Knopf bow making families

Read: My Space: Ekkard Seidl

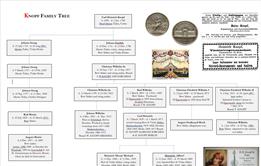

Knopf dynasty: A tangled web

Three bow makers of the Knopf family are well known: Christian Wilhelm, Heinrich and Henry. But the dynasty comprises more than a dozen members, many of whom deserve recognition. Gennady Filimonov draws on archive material supplied by the Knopf descendants

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Cutting corner blocks: inside the Markneukirchen violin factory

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

No comments yet