Peter Quantrill visits London’s Wigmore Hall for the performances of Schubert, Beethoven and Widmann on 18 and 19 January 2025

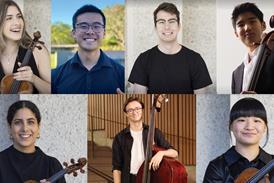

The Emerson sounded its last notes in 2023, nearly unchanged in personnel since its establishment back in 1976. At a pair of compelling matinees, the Juilliard presented the alternative case for a quartet’s evolving identity. Its three female members have all joined within the last decade, most recently violist Molly Carr in 2022. There was, all the same, a formidable unanimity of direction and expression to its playing of late Beethoven and Schubert.

With Schubert’s final quartet, D887 in G major, standing alone at a Coffee Concert, the omission of important repeats seemed an opportunity missed. The Juilliard nonetheless made it an authentically gruelling experience, giving the introduction its due symphonic breadth. Isolating and italicising the transcendent main second subject also served to blur any useful distinction between nominally Classical, Romantic and even Expressionist approaches.

In perhaps his single most demanding work, Winterreise notwithstanding, Schubert doesn’t make life easy for anyone, performers and listeners alike. Some ‘wide’ tuning from leader Areta Zhulla took a while to settle. Whatever it lacked in definition, however, the Juilliard held a sure grasp of the piece’s huge form. Incisive phrasing underlined the pervasive instability between major and minor. The slow movement’s abrupt eruptions of violence were all the more unsettling for breaking the grave mood set by Astrid Schween’s imploring cello solo. The relentlessly circling momentum of the Scherzo and finale embodied existential exhaustion while never succumbing to it.

The following day’s lunchtime concert opened with a no less probing account of Beethoven’s op.130. Once more shorn of its repeat, the first movement unfolded with a steady pulse and old-school purpose rather than following the modern trend to maximise its strategies of disruption. Divisions of that pulse shrewdly motivated the following movements. If Zhulla played to the gallery in the Cavatina, she was in good company, with the likes of Peter Cropper and Günter Pichler. In place of the Grosse Fuge, Beethoven’s shorter, substitute finale made sense in prefacing the Eighth Quartet by Jörg Widmann.

As the third in a series of ‘Beethoven studies’ for quartet, Widmann leads the ‘Danza tedesca’ from op.130 through a hall of broken mirrors, in company with other obsessive Beethovenian motifs such as the Scherzo from the Ninth Symphony. The drawback to this approach is that the original material is already so strong, and so strange, that no amount of reflecting and complexifying can make it more so, like mashing up The Last Judgement or a Shakespeare sonnet. The Juilliard, however, was master of its rhythmic intricacies, giving much more than a straightforward, ‘new music’ performance. That it should believe in it so wholeheartedly, having given the premiere back in 2021, issues a persuasive invitation to listen and to try again.

PETER QUANTRILL

No comments yet