Tully Potter reviews Thomas Wolf’s comprehensive biography of the 20th-century violinist

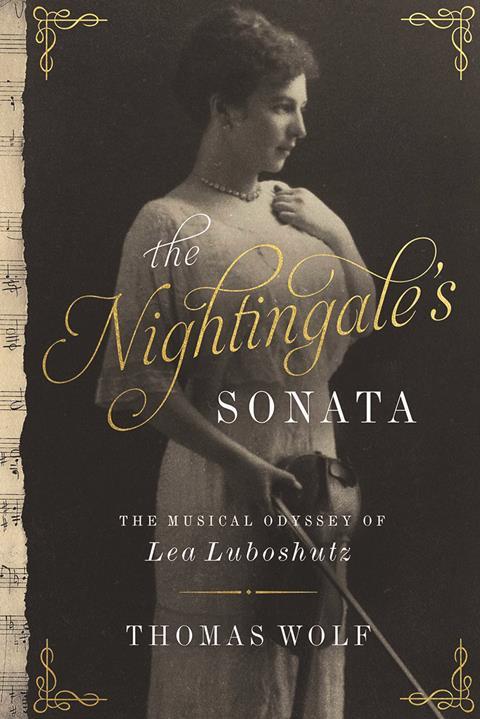

The Nightingale’s Sonata: The Musical Odyssey of Lea Luboshutz

Thomas Wolf

378PP ISBN 9781643130675

Pegasus Books £19.99

I found this book fascinating. Like other Jewish musicians from the Russian sphere of influence, Lea Luboshutz (1885–1965) lived in times that were too ‘interesting’ for her own safety and peace of mind. Her grandson has researched the restrictions on Jews in Imperial Russia exhaustively, and although I knew something of their way of life from other sources, I had not previously read such a thorough exposition. The book’s title refers to Lea’s 1717 Stradivari, the ‘Nightingale’, and the Franck Sonata, her favourite piece.

The name Luboshutz – one can see why Lea and other family members ditched the original ‘Luboshits’ on coming to the West – has long been familiar to me from Lea and her younger brother, pianist Pierre; but I had not realised there was a middle sibling, cellist Anna, who enjoyed a distinguished career in the Soviet Union. They were born in Odessa and father Saul dreamed of a family trio like the Cherniavsky Trio of siblings from that city – the author seems unaware of that fabled ensemble, who travelled the world. Lea started the violin with her father and at eight was taken on by Emil Młynarski at the Odessa Conservatory. Auer offered to teach her in St Petersburg but her parents could not afford for one of them to accompany her. As they had relatives in Moscow, she went there in 1900 to the distinguished Czech pedagogue Jan Hřímalý. In due course she had two periods of study with Eugène Ysaÿe in Belgium. In 1903 she became involved with radical lawyer-politician Onissim Goldovsky, an excellent pianist, and she was with him until his death in 1922 although they never wed. In the 1920s she had a duo – and probably a fling – with Josef Hofmann.

Lea was best known as a soloist, mixing with such luminaries as Casals and Koussevitzky. She visited the US in 1907 but had to cut her tour short because she was pregnant. Emigrating after the Revolution, she found her way back to the US, where she continued her career and taught at the Curtis Institute from 1927.

Having previously played an Amati, she acquired her Strad in 1928. She knew tragedy, losing not just Goldovsky but one of her sons (in a climbing accident). Her elder son Boris Goldovsky had a good career as a pianist and opera impresario, and her brother Pierre was half of the famed Luboshutz-Nemenoff two-piano team. Lea retired in 1947.

Thomas Wolf, himself a musician, knows his stuff, writes well and makes few errors in a text teeming with detail. He includes a number of photographs, interesting in themselves: those of Lea Luboshutz depict a handsome woman and a strong character. I hope he will forgive me when I say that the last section of his narrative, dealing with his generation of the family and particularly his brother Andrew, fails to grip me as Lea’s story does.

Given her eminence, it beggars belief that Lea recorded only three brief pieces by Popper, Arensky and Cui for G&T around 1909. Thanks to the collector Julian Futter, I have long had them on a private CD of historical Russian violinists that he compiled. They are brilliant, especially the Popper–Halíř Elfentanz. Wolf says she resisted offers from American record companies. Let us pray that some live performance turns up, preferably of the Franck Sonata.

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet