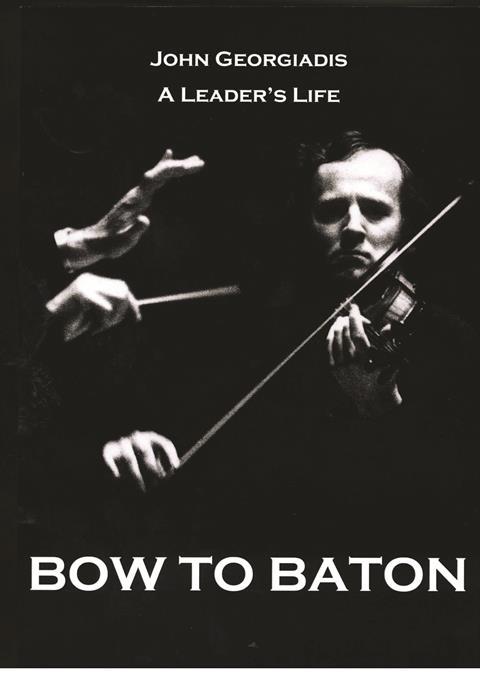

Tully Potter reviews the long-awaited autobiography of violinist–conductor John Georgiadis

Bow to Baton: A Leader’s Life

John Georgiadis

408PP ISBN 9781727426649

Amazon Publishing £38

When I returned to Britain from South Africa in the mid-1960s and began going to London concerts, two orchestral leaders in particular caught my eye. Hugh Bean would bustle on to the platform in a friendly but authoritative way, as if to reassure the audience that all would be well. John Georgiadis gave promise that we were in for really classy entertainment.

When I later interviewed him, he was thoroughly friendly and revealed that he nipped around London to rehearsal and recording sessions on a motorbike, taking his second-best violin with him. In this overdue memoir we learn that he came from tradesman stock: his Greek grandfather was a furrier in Southend, where John was born in 1939; and his father Alec, a self-taught amateur violinist, bought and sold rabbit skins in London. At six John was started on the violin by his father but was soon passed on to Vanna Brown in Kent, where the family then lived. She discovered he had perfect pitch. His next teacher was Joan Rochford-Davies at the Junior Royal Academy of Music.

Georgiadis’s account of his violinistic upbringing is interesting and should be read by today’s teachers. He led the RAM first orchestra, a good preparation for his future career. A year in Paris with René Benedetti was uninspiring but back home he began getting good orchestral jobs.

At 23 he landed his first leader’s post with Hugo Rignold’s City of Birmingham SO and in 1965 he arrived at the London Symphony Orchestra, with which he is still linked in the public’s mind, for his initial spell as leader (he left in 1973, returned in 1976 and finally left in 1979, returning occasionally as a guest). The LSO was all-male and Georgiadis’s reasoning on this point seems strange today. Even stranger is the crazy schedule the LSO players endured, with a heavy recording diary on top of their concert work. His orchestral memories are fascinating and, like his detours on violin playing, often thoughtful. Those who enjoy reading about conductors being discomfited will find stories against such figures as Previn, Mehta, Abbado, Sargent, Szell, Ozawa and Ormandy. Barbirolli, Boult, Fricsay and Pritchard emerge unscathed, but Georgiadis’s main admiration is reserved for Celibidache.

Georgiadis made many solo appearances and recordings, including the Moeran Concerto. In the latter part of his career, of course, after lessons from Celibidache, he has fallen from grace and become a conductor himself, holding several chief conductorships but best known for Johann Strauss concerts and records. He gave up playing in 2010 but made a brief comeback the next year for the film Quartet. Chronicled with plenty of anecdotes, some of them hilarious, and many photographs, his life has been quite a roller coaster.

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet