Conductor Peter Manning explores the historical and musical context of the work, ahead of a performance with Chromatica on 11 February

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Understanding the background of composers can be speculative, but considering the musical and practical environments they navigated often provides valuable insight into their creative processes.

In this case, we examine one of the central pinnacles of the orchestral repertoire: Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for Solo String Quartet and String Orchestra.

Genesis

In 1904, a crisis arose when Sir Henry Wood, conductor of the renowned Queen’s Hall Orchestra in London, refused to work with deputy players. This led to the formation of a new orchestra, which re-emerged later that year as the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO).

Elgar, already familiar with many of the musicians from their time in the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, developed a close friendship with William (Billy) Reed, LSO’s sub-principal violinist. Their collaboration culminated in the first performance of Introduction and Allegro, featured in the LSO’s inaugural all-Elgar concert in spring 1905 at Queen’s Hall.

Elgar rehearsed the solo quartet—Arthur Payne (leader of the LSO), W.H. Eayres, Alfred Hobday, and Bertie Patterson—at Frank Schuster’s house in Maidenhead on 4 March. Schuster, a great patron of Elgar, hosted the composer regularly. The full-orchestra premiere followed at Queen’s Hall on 8 March 1905.

The Build-Up

In preceding years, Elgar had made numerous visits to Bayreuth to hear Wagner, corresponded with Mahler, and begun a lifelong friendship with Richard Strauss. His European travels around this period also inspired the concert overture In the South (1904), which immediately preceded Introduction and Allegro.

With the groundbreaking LSO and its excellent players, Elgar felt he could fully explore the potential of an exceptional string orchestra. He drew inspiration from Bach and Purcell—two composers he deeply admired—whose earlier models of string concertante writing influenced the structure of Introduction and Allegro, incorporating a solo quartet within a larger string ensemble.

At the heart of the work lies an intricate polyphonic texture. Elgar’s deep understanding of the violin—evident in his Violin Concerto, written for Fritz Kreisler, and in left-hand finger exercises he created for Jascha Heifetz—enabled him to extend the emotional, textural, and tonal palette of the string orchestra. His writing in this piece elevated the virtuosity of orchestral strings to an unprecedented level.

The Music

Notable for its expressive intensity, Introduction and Allegro shares a dramatic energy with In the South. The work’s florid, dynamic string writing extends not only to the violin but also to the viola, cello, and double bass. This focus on the full range of string instruments had already been evident in the prominent viola solo of In the South.

Elgar’s ability to achieve a broader orchestral sound within a smaller ensemble is remarkable. His understanding of counterpoint and extended melody is evident in his pairing of instruments to create rich textures. The influence of Beethoven’s string quartets and Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante can be heard in the work’s structure. One striking example is the viola solo four bars after Figure 2, where Elgar demonstrates his mastery of musical voicing.

The piece moves between intense, full-bodied passages and moments of delicate transparency. The contrast between fortissimo and pianissimo is handled with an unrivalled sense of balance. This careful dynamic control, paired with his signature rhythmic drive—foreshadowing the first symphony (1907)—makes Introduction and Allegro a work of extraordinary power and sophistication.

Careful dynamic control, paired with Elgar’s signature rhythmic drive makes Introduction and Allegro a work of extraordinary power and sophistication

Technical Mastery

Elgar’s meticulous notation style, with precise articulation markings, likely stemmed from his early experiences with amateur musicians in English music societies. This attention to detail ensured clarity of intent and expression.

However, the sheer complexity of his music never overshadows its emotional depth. Introduction and Allegro breathes with natural energy across its 15-minute span, demonstrating a composer whose understanding of string instruments was entirely self-taught.

Elgar once stated, ’My idea is that music is in the air, music is all around us, the world is full of it, and you simply take as much as you require.’ This philosophy is palpable in Introduction and Allegro, where he weaves lyrical melodies with intricate counterpoint, creating a sound world both ancient and timeless.

A Personal Reflection

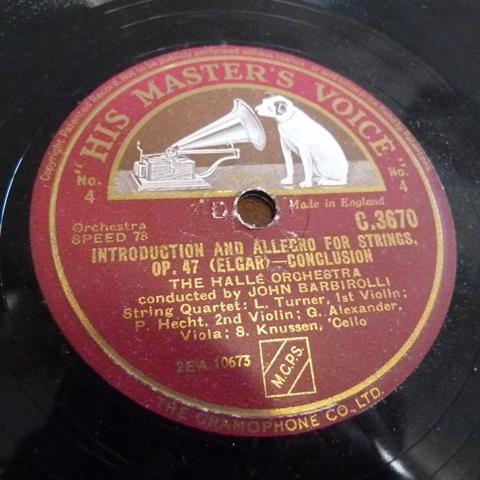

My first encounter with this masterwork came during childhood violin lessons with Laurence Turner, leader of Barbirolli’s Hallé Orchestra. He played me his 78-rpm shellac recording of Introduction and Allegro, conducted by Barbirolli in 1947 (released in 1948 as HMV matrix no. C3670, see below). It was a transformative musical experience.

That recording was overseen by Fred Gaisberg, the legendary artistic director of HMV, who had been a key supporter and friend of Elgar’s. Together, they helped shape the early recording industry, ensuring that Elgar’s music reached a wider audience at the dawn of the 20th century.

Decades later, I had the privilege of recording the piece with Vernon ‘Tod’ Handley and the LPO for EMI. My appreciation for Elgar’s string writing has only deepened, as has my admiration for the enduring legacy of British orchestral music.

Conclusion

Though Elgar’s world is now far behind us, his music remains a testament to his genius. The complexity, beauty, and deep emotional expression in his compositions continue to resonate. The inscription on the title page of his Second Symphony, quoting Shelley—’Rarely, rarely cometh thou, spirit of delight’—captures the essence of his creative impulse.

In Introduction and Allegro, Elgar not only pays homage to the past but also forges a new path for orchestral string writing, producing a work of extraordinary brilliance and lasting significance.

Peter Manning is founding artistic director of Chromatica, a new orchestra that supports musicians at the beginning of their professional careers. Peter conducts Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for Solo String Quartet and Strings at Wilton’s Music Hall on 11 February 2025. Book now here.

Read: Recovering paradise: Alisa Weilerstein on Richard Blackford’s new climate change concerto

Read: Why I write my own cadenzas: violinist Lir Vaginsky

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet