The Sibelius Violin Concerto played a pivotal part in the Soviet-born violinist’s life – even though it was unknown to her until the age of 18

I never heard the Sibelius Violin Concerto when I was young. I grew up listening to records by Leonid Kogan, who was my teacher later on, and for some reason he never recorded the Sibelius. So I first heard it while watching the finals of the 1978 Tchaikovsky Competition aged 18. The US violinist Dylana Jenson played the Sibelius in the final, coming second, and I knew then that I wanted to play it. Then I couldn’t find the parts and I had to take pictures of the pages on a camera when I finally got them. It’s a difficult piece to learn, and I spent time working on it with my teacher, Volodar Bronin. As I didn’t have any recordings, unlike most of the other repertoire I practised, I just played it the way I thought it should be played, so it became completely my piece and no one else’s.

When I entered the 1980 Sibelius Competition, I knew I had to win it. A first prize would mean I had a chance to enter more competitions and possibly have a solo career; second place might have meant I taught violin in Siberia for the rest of my life. I played the Sibelius Concerto in the final round, and I did come first, but what I remember is how the Finns fell in love with my performance. I’ve always had an affinity with Finland, and I sometimes wonder if my ancestors might have come from there. It’s a beautiful land with a kind of cool Romanticism about it. The music is the same, all very contained and introverted but with a smouldering passion inside – just as the Finnish people tend not to show their emotions, but are very emotional and I’ve often noticed how they can cry very easily.

Much later, I played the concerto with Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting, and he stopped when we got to the second theme of the third movement. ‘It’s too dance-like,’ he told the orchestra. ‘In Finland it would be much heavier, to give it the right Nordic character.’ As soon as the orchestra played it like that it made sense to me, and since then I’ve always played it a little slower and heavier.

For a long time I had trouble with parts of the concerto, particularly in the third movement. It only changed for me five years ago when I had an accident while climbing in the Carpathian mountains. I slipped and landed on the middle finger of my left hand, which swelled up to twice its size. I was playing the Sibelius in China a few weeks later, and I thought I couldn’t possibly play such a difficult piece like that. I went anyway, and practised it without putting any pressure on that finger. Suddenly, all the passages I’d struggled with for 30 years were easy! I was forced to change my technique and it had this incredible effect – I had one of the best reactions from any audience that I can remember, and I’ve always played it the same way ever since.

The Sibelius was also the first concerto I ever recorded. It was in 1985, Seiji Ozawa conducting the Boston Symphony, and they’d booked just two hours for the Sibelius Concerto and three for the Tchaikovsky. Standing in front of the orchestra, I could see the producer in the production box looking worried; I later found out he was muttering, ‘That’s another $400!’ They were counting the seconds as I was tuning up! I treated the whole thing as a live recording, as we had so few takes, and it was great preparation for my recording career.

The best advice I can give to someone practising the concerto is to listen to as many other Sibelius works as you can, by interpreters such as Salonen and Paavo Järvi – and if possible, visit Finland. You have to feel that Finnish spirit when you play it, and be able to make people feel it too.

-

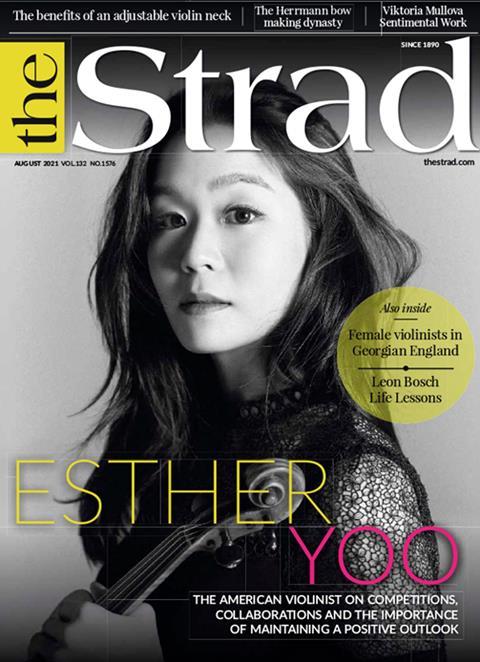

This article was published in the August 2021 Esther Yoo issue

The American violinist on competitions, collaborations and the importance of maintaining a positive outlook. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- American violinist Esther Yoo

- The benefits of an adjustable violin neck

- Bach’s Solo Violin Partitas

- The Herrmann bow making dynasty

- Female violinists in 18th-century England

- Making accurate arching templates

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet