Ross Harbaugh talks through some exercises designed to develop balance and technique

T'ai chi, a meditative form of martial art, and cello playing are both based on balanced, coordinated motion using momentum, anticipation and natural body movement. They can be seen as beautiful, disciplined sequences of dance-like gestures: the subtle changes that occur in the body, arm and hand while producing a legato passage of music are complex yet fluid; and the coordination between the arms as the cellist moves to a high position on the fingerboard has a definite liquid quality. Exploring these motions away from the cello while learning the basic gestures of t'ai chi is a fun exercise that also offers cellists a deep physical and mental stimulation.

Breathing

Controlled breathing is essential to free the muscles and energise the brain and body. Novice cellists often forget to breathe while playing the cello because they do not regard breathing as a conscious activity.

Stand comfortably with knees slightly flexed and exhale, counting to three. When you inhale, also count to three. Feel the rib cage expand and the nostrils flare. Breathe in through the nose and out through the mouth. Let the tongue lightly touch the upper teeth as you exhale to cool the tongue, creating a slight hissing sound. The movement should be unforced and fluid.

As you breathe, notice the change from exhalation to inhalation. This is very similar to the turning point of the bow arm and hand at the end of a bow stroke during a slow legato. In both breathing and bowing, the movement in one direction gradually slows, stops and gradually starts in the other direction - the lungs begin to fill and the bow begins its return journey.

Connection

The chi in t'ai chi refers to the life force, or power that flows through the body and motivates it. It is said to flow from the ground, up through the legs and body and out through the fingertips. To ensure this flow, it is essential to feel connected to the floor through the feet. Connection to the floor is also a hidden source of power for the cellist.

Imagine the soles of your feet sinking into the surface you are standing on, as if the feet are taking root. You can rotate the balls of the feet one at a time into the floor to emphasise this feeling of connection. Place the feet at shoulder width with the toes pointing directly forward, not splayed as if standing to attention, then flex the knees slightly. The sensation is of stability and flexibility, like a tree.

Balance

The benefit of standing in the connected t'ai chi stance is an amazing sense of balance. The upper body can sway and twist while the feet remain rooted to the floor. It's easy to stand this way for long periods of time and the feeling of balance gives great confidence and freedom.

Stand with the feet evenly placed under the body so that each leg is carrying half the body weight. Feel the soles of the feet connected to the floor and breathe using the controlled technique described above. Gradually transfer body weight to your bow arm side so that three quarters of your weight is over your right leg. Feel the right leg fill with weight and the left empty of weight. Gradually transfer weight back to the centre and then to the left.

Fluidity

All t'ai chi motions are performed with a fluid, legato movement - like the motions of a natural cellist. One of the secrets of fluidity is knowing the destination before starting the journey; this is the concept of anticipation that Janos Starker taught so effectively.

Stand with the feet shoulder width apart, toes straight ahead, knees slightly bent, spine straight. Relax the shoulders as your arms begin to rise. Keep the shoulders relaxed, and let the arms follow the hands, as if the wrists were being held and lifted by two encircling ropes. When the hands reach chest level, let the arms begin to sink back down with the hands following and the palms out. The hands always follow the arms and the arms always lead the hands. The hands should trail behind as if the entire gesture is being performed in thick liquid.

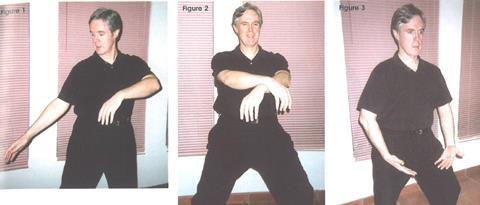

Rotation and momentum (figure 1)

The free rotation of the body is possibly the most important element of t'ai chi for cellists. The body moves a great deal, nurturing a freedom of motion that is very useful for everyday work on the cello. A lot can be gained by allowing the trunk to open to a greater or lesser extent, or to counter-rotate on every bow stroke. For rigid students or more inhibited players, this release of the body awakens the possibility of motion and is a significant development in the search for comfort and power when playing the cello.

Stand with the feet wide apart. Let the arms start to swing, both to the left, then both to the right, the way that children swing their arms in the playground. Gradually increase the power of the swing by activating the quadriceps, the big muscles of the legs. The piston motion of the legs bending and twisting and then unwinding vigorously seems to pump energy up from the floor, through the legs and into the torso trunk. Thus the rotation of the trunk and the swing of the arms is free and largely passive. When sitting at the cello, the rotation is more subtle and is initiated more by the body trunk, but the valuable momentum and centrifugal motion of the arms is still present and dramatically useful to the cellist.

The following t'ai chi postures form an excellent routine for cellists.

Bear paws (figure 2)

This basic breathing and stretching technique is similar to an exercise taught by the influential cello teacher Margaret Rowell. Let the arms hang freely from the shoulders, with the wrists crossed in front and the hands draped as if the forearms are resting on the strings of the cello. Slowly lift the arms up, keeping the wrists crossed and the hands passive, breathing in and looking towards the sky. When the lungs are full and arms vertical, breathe out slowly, separating the hands and quietly bringing them down to the sides of the body, palms flat and facing out. Repeat four times and then begin to augment the breathing out by letting the knees bend and the body sink while keeping the back line straight. The hands hang passively as they are lifted, but actively extend on the smooth descent. If we think of the cellist as a singer then the relaxed hand is the throat.

Lifting cello chi (figure 3)

Stand with the weight of the body distributed evenly between the feet. Fill your lungs with a slow, deep breath and feel your spine lengthen as you look up. Empty the lungs and again feel each foot's connection to the floor. Make the breathing a visual experience by lifting the loosely cupped palms of the hand up to chest level as if lifting something precious, but extremely light. Now turn the palms over and make a slow spreading motion downward and outward as if your palms were stroking the surface of a huge vase. Breathe out slowly. As your hands slide under the bottom of the vase, exaggerate the downward sinking motion by bending your legs while keeping your spine long, as if your back were leaning against a wall. Now lift the imaginary object again with both hands, straighten the legs and return to the starting position.

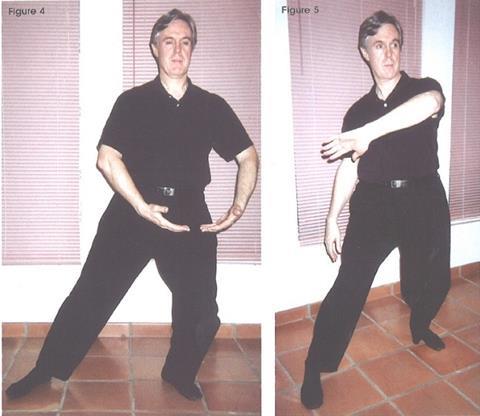

Alternate this lifting and filling motion with the spreading and emptying motion. Once this flow is comfortable, start transferring your body balance to the side of your cello bow arm. Your right leg will gradually bear more of your weight until your body is balanced over the right leg. When you feel that about three quarters of your body weight is over the right leg and one quarter is still over your extended left leg, scoop with your hands, breathe and lift the 'energy' as you transfer your balance back to the centre; then repeat the technique on the other side (figure 4).

Each body gesture used when playing the cello involves muscles that tense, making the limb move, and muscles that relax, allowing the motion to take place. When you focus on the muscles that relax, cello playing seems effortless. Musically, every phrase fills with tension and then at some critical point, empties of tension.

Open the trunk (figure 5)

This is a sequential flow of the body's trunk, shoulder, arm and hand. Begin by moving only the right shoulder, rolling it forward. Go on to perform several rolls forward and backward with each shoulder. As the shoulders roll, the body should not be rigid but allowed to follow the forward or backward motion of the shoulder.

As the body rotates, following the lead of the shoulders forward and backward, the upper arm is allowed to lift, with the forearm and hand streaming behind like a banner. Next, allow the forearm to lift with the palm of the hand facing in. The face and chest should follow the palm as it streams in slow motion. The upper arm is parallel to the floor and the forearm is suspended effortlessly with the thumb pointing towards the ceiling.

The hands should remain loose. Now lift the bow arm so that the hand is facing out. This feels more like playing a down bow. We draw slow, tenuto down bows across our bodies. The face and chest follow the hand ensuring rotation and the power of balance and centrifugal force. We repeat this entire sequence with the left arm and hand. One of the especially valuable lessons of this t'ai chi motion is that both sides of the body can perform exactly the same motions and gestures.

Drawing down bows in the air, without a cello, with free flowing bodies and arms, is liberating for the student and teacher alike, since neither of them has to worry about holding a delicate instrument or bow. Natural body motions can be explored and taken to their extremes. A down-bow motion in the arm doesn't need to end at the tip if you are not holding a bow.

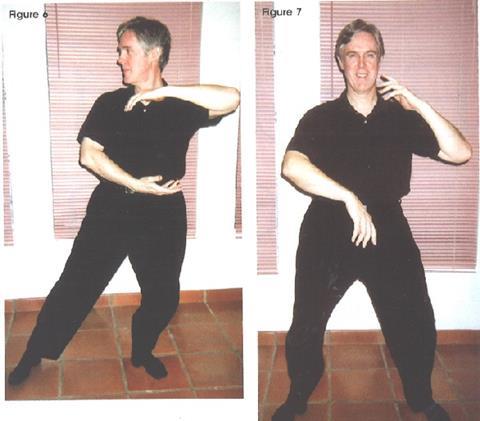

Hold the ball (figure 6)

This is one of the most basic and essential t'ai chi gestures. Gradually transfer three quarters of the body's weight on to the right leg, as before. Raise the right arm in front of the body so that it is suspended at chest height with the upper arm and forearm at the same level. The Palm should remain facing down while the hand is relaxed and hanging down in a very cellistic way. The palm of your left hand, however, should face up and be placed underneath the right hand as if You were holding a beach ball. The upper hand is passive and the lower hand is active.

Now, let the hands fall slowly in front of your body, and transfer the body's weight to the centre. Gradually reverse the procedure by transferring most of your body's weight to your left leg and repeating all the movements on the other side. Repeat these two postures, alternating from one side to the other. Next, let the upper hand side down the outer curve of the imaginary ball'as it changes position from high to bow. Finally, actually push the upper hand out, palm out as the exchange happens. This should feel like a slow, tenuto down bow.

Now hold an imaginary cello instead of an imaginary ball and assume the classic cello position as an observant mime artist might do. Suspend the right arm in the bow position and hang the relaxed right hand from the arm (figure 7). Hold the left hand with the fingers open and the index finger pointing up to the sky. You can now swap positions so that you are playing your imaginary cello backwards. This is easier and more fun than it sounds and is an illuminating exercise in balance transfer.

T'ai chi walking

Knowing how to move across the room while performing complicated arm motions is a basic t'ai chi skill. The movement of the legs and knees balancing the body weight can be viewed as a macrocosm of the movement and function of left-hand fingers on the cello. The student can then study the movement of the left-hand fingers and knuckles by studying the motion of the legs and knees.

Gradually transfer most of your weight on to your right leg and draw up the left leg so that only the toe is touching the floor and the heel is touching the right ankle. The left foot is now in a dynamic position ready for action. Take a small step with the left foot, placing the heel only on the floor at a 45"" angle to the right foot. Gradually move the weight of the body on to the left foot as it rolls off the heel into full contact with the floor' The left leg is now supporting most of the body's weight. Next, transfer the body's weight back on to the right leg, straightening the left leg and pulling the left foot back on to its heel. Pivot the left foot to the left. Now move nearly all the body's weight on to the left leg, while drawing the right heel up to the left ankle. The right foot is now in a dynamic position ready for action.

This sequence of motions is useful when studying in detail the motion and function of the left-hand fingers on the fingerboard. The legs take turns serving as the primary bearer of the body's weight and the fingers of the left hand take turns in bearing the weight of the hand and arm as they play slow, lyrical Passages. This parallel between t'ai chi and cello playing is at the heart of the exercises.

This article was first published in The Strad's September 2003 issue

Read: 11 stretching exercises for musicians

Read: 7 warming up and cooling down exercises for musicians"

No comments yet