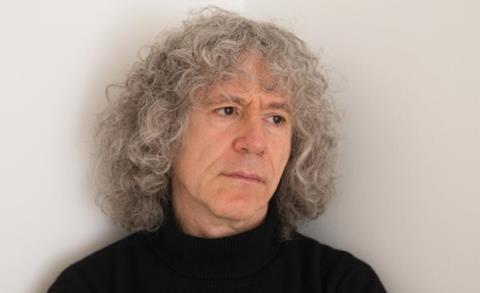

Beethoven’s Cello Sonata no.4 was the gateway the British cellist needed to understand the myriad delights and complexities of the composer’s work

It was in my early twenties that I started studying Beethoven’s Cello Sonata no.4 in C major, and it took me further into the composer’s world than any other piece up to that time. Before that, I’d always had a problem with Beethoven – I couldn’t work out how to play it. I was missing the incredible spirit and strength that’s there from the early music onwards. If you miss that joy, humour and vitality in the music then I think you miss Beethoven. For me, it was the gateway to his later works as well.

I spent hours at the piano when I started learning the sonata, as I do with most pieces. It’s incredibly concentrated, much more so than the Third or Fifth sonatas, and it demands more from the listener to appreciate it. It’s all so closely connected and every note is saying something – if you blink, you’ll miss a meaning. I realised that it’s possible to relate each note of the sonata to the first two bars of the first movement. I’ve never been able to analyse a piece as closely as that, and I think it led me towards an understanding of Beethoven’s thought processes, at least for the later music.

I once played that first movement for a group of children and described the music as ‘Heaven and Hell’. That got their attention but what I actually think is that, where other composers’ music provokes images and stories in your brain, in Beethoven the meaning is in the notes themselves. I found that all I could think of was the notes and how they relate to each other so closely. Compared with the earlier sonatas, it’s like the music has been put in a washing machine and shrunk – he condenses into four bars what you’d expect to take sixteen. That’s why it’s the shortest of the five sonatas. Likewise, I don’t think it’s all that helpful to examine what was happening in Beethoven’s life at the time of writing the cello sonatas. He wrote the Third in A major in 1808, not too long after writing the Heiligenstadt Testament in which he contemplated suicide. But it’s a sonata suffused with joy and love of life, so letting that prey on your mind will just mess up the piece.

Probably the first time I heard the C major Sonata was on the 1953 recording by Pablo Casals and Rudolf Serkin. Casals’s playing really captures the composer’s incredible strength and force of personality – I love listening to him performing Beethoven even more than Bach. I’ve played it with a lot of great pianists myself, in recent years with Robert Levin, who opened my eyes to the incredible accuracy of Beethoven’s markings. Once when we were coming off stage after a performance in Salzburg, I turned to Bob and said, ‘Finally I know what a dash means!’ Beethoven always wrote dashes above the notes rather than dots, except under slurs. So he asked what it meant and I said, ‘It’ll mean short, or long, or soft, or loud.’ What I’d realised was that Beethoven’s markings really were accurate, but they were a message from him to someone who understands him. Part of any interpretation has to be taking every single marking into account, thinking about it deeply and finding what it says to you. I always work from the first edition, or a version checked and approved by the composer.

My advice to someone studying the C major Sonata for the first time would be to start at the piano, get to know the whole score, try to understand not just every note but every marking in the piece, and then keep asking questions about why you’re doing what you’re doing. It’s what keeps you honest as a musician.

-

This article was published in the June 2020 Tetzlaff Quartet issue

The Tetzlaff Quartet members discuss balancing chamber playing with busy individual careers - and recording their first Beethoven album after 25 years together. Explore all the articles in this issue.

More from this issue…

- The Tetzlaff Quartet on recording Beethoven

- A genuine Amati or a clever fake?

- Top soloists discuss working with conductors

- New translations of Sarasate’s letters

- Bows from the courts of Napoleons I and III

Read more playing content here

-

1 Readers' comment