Schnittke’s First Violin Sonata was the Irish–German violinist’s introduction to the composer’s work – as well as the perfect opening to meet the composer himself

My introduction to Alfred Schnittke came when I was 15. I was at the summer school of the Schleswig-Holstein Festival in Germany and heard another student performing his First Violin Sonata. I was gobsmacked; here was music I’d never encountered before, and I immediately went backstage to ask the player if I could copy the parts. After that I never looked back, and tried to learn everything I could get my hands on. Three years later, I was studying with Zakhar Bron in Lübeck, and at a dinner party I heard a couple boasting that ‘a famous composer’ lived in their apartment building in Hamburg. I knew Schnittke lived in the city (although so did other composers, such as Sofia Gubaidulina and György Kurtág) but listening to their conversation I was convinced they were talking about him, so I asked for their address. The next Sunday evening I went there, with a tape recording I’d made of the First Sonata and some other chamber pieces by him. I’d hoped to put it in his letter box, but when I rang the bell to his apartment, his wife came out and asked me upstairs. Schnittke was there in the apartment, delighted to meet me, and we talked about his works for 45 minutes. It was the start of a friendship that deepened throughout the next few years, as we met many times afterwards and had endless talks about music.

I remember one particular question I asked: in 1968 he’d orchestrated the First Sonata for chamber orchestra, violin and harpsichord. When I’d played it that way, we found the harpsichord didn’t have the carrying power for a large concert hall, especially in the second and fourth movements, so I asked him if we could use the piano as well, and switch between the two. He thought, and said ‘Why not just put a microphone inside the harpsichord?’ It was amazing how direct and pragmatic he was, where I must have been quite reverential and shy!

As it happened, this was how I played it with my friend and mentor Yehudi Menuhin conducting, when we toured Germany together in 1999. It caused problems with the concert promoter, who wasn’t happy about having the harpsichord amplified, but Menuhin insisted it should be played like that. It was a startling sound, especially in some of the larger German concert halls – I think Schnittke would have loved it, although of course some people didn’t! Sadly, the final performance of the tour, in Düsseldorf, proved to be our last concert together, as Menuhin died just three days afterwards.

Read Sentimental Work: Amit Peled

Read Sentimental Work: Camille Thomas

Read Sentimental Work: Narek Hakhnazaryan

We had some arguments about playing the First Sonata, beginning with the opening two notes. Menuhin wanted them to sing and be beautifully resonant, but I told him it wasn’t what Schnittke wanted – he’d even called the opening an ‘anti-Romantic statement’. Menuhin countered: ‘There’s no such thing! It goes against the rules of expression for the violin.’ Still, I went ahead and played it on stage how Schnittke wanted. On the one hand I would always try to please Menuhin, but I also wanted to express my own individuality.

Zakhar Bron, my most important teacher, also spent a lot of time with me on this piece. So many things I do now are down to him, including the fingerings and bow distribution. His rule is: less bow means more sound, as it concentrates the pressure. I still think about that when it comes to sound production. Bron also insisted I learn the sonata by heart, and it’s one of the few chamber pieces I still play from memory. It gives me so much flexibility in the second and fourth movements where the rhythms are so complex. I’d encourage anyone to learn it, particularly the orchestral version – especially in this day and age, when all of us are obliged to think about smaller ensemble set-ups.

-

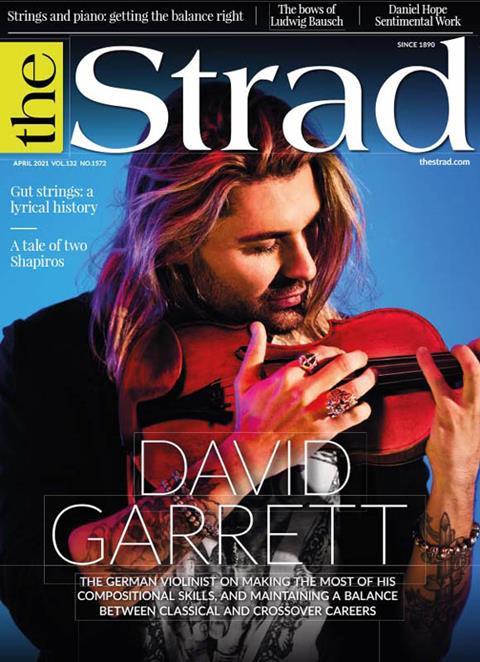

This article was published in the April 2021 David Garrett issue

The German violinist talks about making the most of his composition skills, and maintaining a balance between classical and crossover careers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Crossover star David Garrett

- German bow maker Ludwig Bausch

- Janusz Wawrowski: Session Report

- Germany’s 19th-century gut string makers

- Two Shapiros: 20th-century US female violinists

- Creating a balance between strings and piano

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet