An intense seven-year period of study at the Moscow Conservatoire was hugely influential

This article first appeared in The Strad in September 2010. Download on desktop computer or throughThe Strad App.

After my father, my main influence was Mstislav Rostropovich, with whom I studied for seven years. When I first came to play to him I brought Prokofiev’s Symphony–Concerto. This was my audition piece for the Moscow Conservatoire, where Rostropovich taught, but first of all I had to play for him.

Trembling, I went to his flat in Moscow. It was strange to see him face to face after seeing him on stage. He offered me a snack because he said that before I played I must eat something. There was a very big table and a plate on which was what I thought was a fried egg that he said he’d cooked himself. I tried to eat it but couldn’t – it was made of rubber! You can imagine the effect on me – I didn’t know such things even existed. He was travelling all over the world at the time and had brought back a few toys like this from America – all sorts of things, including a giant rubber hammer with which he enjoyed frightening people. With me I don’t know what his impulse was: perhaps to make me feel at ease? If so it didn’t work: I was completely overcome. But he enjoyed the whole thing enormously – it was a good joke. He liked challenging people: he wanted to see how one would behave in a situation like that. Then, after I’d played the second movement of the Prokofiev, he gave me some exercises – playing double-stops two against three – to see how quick my reactions were and how flexible my mind was. I might have spent a lot of time preparing the Prokofiev, but how would I react when asked to do something I hadn’t done before?

- Watch: Sheku Kanneh-Mason meets Rostropovich's Cellos

- Watch: Testing a copy of a Rostropovich cello

- Watch: Mstislav Rostropovich gives Dvorák Cello Concerto masterclass

In lessons he worked a lot on the production and projection of sound. Sometimes in a lesson he would look at you and it was just like being emotionally X-rayed: he was seeing straight into the heart of your personality. He opened doors emotionally and psychologically for you as a performer, as a person, on top of what he gave you as a musician. It was all done to release your potential.

In those years Russia had a rigidly structured system of education, very controlled – rules had to be followed. But the atmosphere in his class was quite different. I remember once I played the E minor Brahms Sonata. He was teaching from the piano, as often he did, and said, ‘Rukha,’ (short for ‘starukha’ – old woman – which is what he called me all my life, from the age of 18), ‘you haven’t shed enough tears in your life.’ That was one of the phrases that stuck – now I know how right he was. When you performed he made you put into it everything you had ever experienced in your life, as he did. He never spared himself, either on stage or off. Before I went to Rostropovich I had been in the Gnessin Institute and he used to tease me that too much of my playing consisted of ‘Gnessinskie strishochky’ – over-careful, over-polished bow strokes, not free enough emotionally. ‘Let it all hang out!' he would shout.

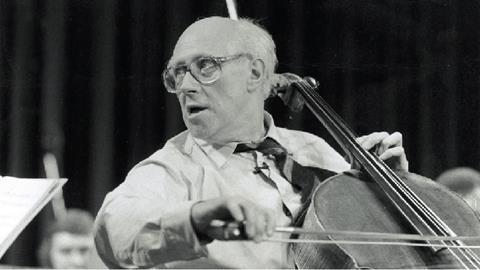

I remember in particular concerts he gave in the Great Hall of the conservatoire, the Prokofiev Symphony–Concerto, Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto, and the first performance of the Second Concerto at which Shostakovich himself was, unforgettably, present. Whenever I heard him, what struck me as irresistibly special about his playing was its unsurpassed brilliance and projection, its enormous expressivity and the sheer volume of his sound, as well as his palette of colours. He would go on stage and start to play, and not for a second would he let you go until the end of the piece. He would hold the attention of the audience every moment he was on stage. He tried to instil that feeling in his students as well: you had to give everything on stage. He had a sheer power in projecting his sound – I can’t think of anyone who can compare. When you look at his playing you see the perfection of his relationship with the cello, especially the freedom of his right arm, which was a part of the work we did with him. Early on he also gave me several miniature pieces in order to work on different kinds of vibrato. When I came to him I didn’t have enough volume or a big enough palette of colours.

This article first appeared in The Strad in September 2010. Download on desktop computer or throughThe Strad App.

Photo: Julia Hedgecoe

![[1] Soyoung Yoon pc Julia Wesel](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/6/6/1/33661_1soyoungyoonpcjuliawesel_954281.jpg)

No comments yet