For Renaud Capuçon, recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra and Simon Rattle was a dream come true – and one that he couldn’t allow to be derailed by Covid-19’s lockdown restrictions, as he tells Charlotte Gardner

The following is an extract from a Session Report in The Strad’s January 2021 issue in which violinist Renaud Capuçon talks about recording Elgar with the London Symphony Orchestra and Simon Rattle during the pandemic. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The January 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

‘I’ll never forget the start of our very first run-through,’ says Capuçon. ‘You could feel that this orchestra had performed the world premiere with Kreisler, and recorded with Menuhin and Heifetz. Of course, they’re not the same players but the sound remains. You can feel that it’s in their blood. Certainly I have my view of the work and my own sound – and Simon and I initially connected to the playing style of Albert Sammons on his 1929 recording with Henry Wood and the Liverpool Philharmonic as we prepared together. But when you hear that first tutti played by the LSO, you don’t begin your own first note as you would with another orchestra and conductor. It’s not that it’s right or wrong – it just feels like home.’

Less homely was an orchestra wearing masks, with plastic windows on their stands and everyone spaced out around LSO St Luke’s in an almost-complete circle around Rattle. Yet still it worked. ‘I was very impressed with how the players handled having masks on during the sessions, and although I was scared that the seating arrangement might feel too distant, the circle actually felt closer.’

Read: Session Report: Right place, right time

Watch: Renaud Capucon plays Hungarian Dance No. 5

Rattle’s way of working also felt like a luxury. ‘Everybody knows how gentle and focused he is,’ begins Capuçon. ‘He also does long takes, which I really loved, especially for this piece which is made solely of long phrases. I know the work well, having played it so much, so I performed every take almost like a concert, really giving everything. In fact, everyone was so happy to be playing that they gave 600 per cent energy. It was particularly noticeable when we made mistakes. It’s inevitable that mistakes are made when you’re playing for two days, but when you’re tired you can try to redo things and they still don’t work, whereas we were able to fix things easily and move on. We were on fire! At the end we played the whole concerto through again in one take, as a concert for five people from the record company.’

-

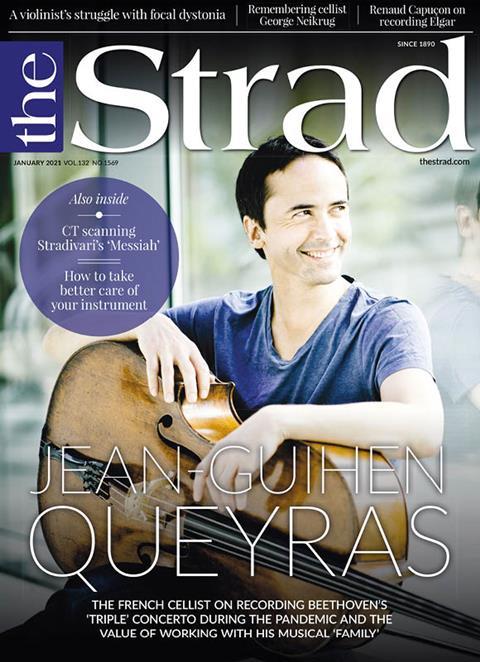

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue.Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

- CT scanning Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’

- Remembering cello tutor George Neikrug

- Renaud Capuçon on recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- How players can take better care of their instrument

- Playing Tchaikovsky with just two left-hand fingers

Read more playing content here

No comments yet