In this extract from September 2018, Joe Robson examines the history and prestige surrounding the colour red and how it began to feature in Stradivari’s instrument varnish

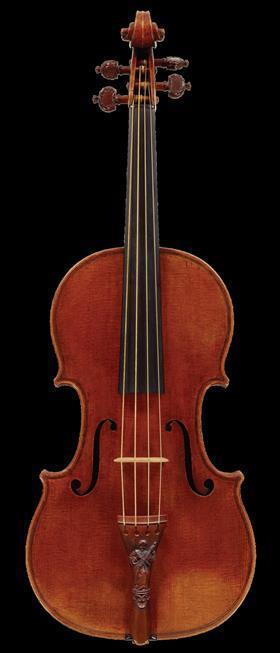

The exemplary red varnish of Stradivari’s 1721 ‘Lady Blunt’

‘LADY BLUNT’ PHOTO COURTESY TARISIO

The following is an extract from the article ’Stradivari Varnish: Scarlet Fever’ from the September 2018 issue. To read the full article, click here

Human beings see the colour red and its variations better than any other mammal. The significance of red in our lives goes back to the Neanderthals, who buried their dead in red ochre. Every human culture has assigned some version of power to this colour. In ancient China it was the colour of health and prosperity. In the Arab world it signified divine favour and vitality. The Roman Empire was ruled by a class whose name, coccinati, literally meant ‘those who wear red’. It is the colour of kings and queens, cardinals and demons; in 1559 Cosimo de Medici memorably stated, ‘A gentleman can be made with two yards of red cloth.’ In medieval Europe the dye and cloth trades flourished as they supplied the rich and powerful. And throughout our history we have sought a better source for red dye: these included ochre, madder, orchil, lac, oak-kermes (vermilion) and St John’s Blood (Polish cochineal).

When Hernán Cortés began the conquest and plunder of the Aztec Empire in c.1518 he easily identified kings and royalty by their appearance, since they were dressed in cloth and feathers dyed in the finest reds and purples a European had ever seen.

Cortés sought and found the gold he promised the Spanish court. However, as the news of this magnificent red reached Spain, a new explosion of wealth and power there was fuelled by a tiny insect: the cochineal bug. A group of Spanish families formed a cartel that controlled the trade and fed the eruption of demand for dyes made from cochineal. This funded the reign of King Philip II and the creation of the Spanish Armada. It also served to underline the hatred and competition between Spain and England, as Philip had been consort to the vilified Mary Tudor.

Mary’s half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I, loved the colour red so much that she had her ladies-in-waiting dressed top to toe in red, just so she could look at them. She was also keen to take advantage of both the riches of the Spanish and the British animosity towards them, and funded expeditions by privateers such as Francis Drake (whose family was in the cloth trade) to attack the Spanish treasure ships. She helped finance his ship, the Pelican (later renamed the Golden Hinde) and personally attended the ship’s launch for its maiden voyage. As he prepared to leave she secretly instructed him to capture Spanish merchant ships sailing from Mexico; Drake wrote of his ‘great hoepe’ of a ‘cochinillo’ prize. Rightly so: in 1589 English raiders captured 30,000 pounds of cochineal from a single treasure ship, possibly 10 per cent of the dyestuff’s harvest, and in 1592 a further 50,000 pounds was taken from another vessel, the Madre de Dios.

In 1597 Elizabeth’s favourite, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, won the largest cochineal prize of the century in a raid off the Azores: 55,000 pounds, a value equal to about 12.5 million grams of pure silver. Essex paid royalties to the Crown on a value of £80,000. He then purchased the cargo for pennies on the pound and the Queen declared no cochineal could be imported for two years, giving Essex a monopoly on the dyestuff.

During Elizabeth’s reign, the value of the cochineal pirated by Drake, Essex and others was equal to half of the value of the treasury of England at the time. For two centuries following Cortés’s arrival in Mexico, the value of cochineal closely matched that of silver, at about 1 gram of pure silver = 1.8 grams of cochineal (approximately 35 dead insect bodies). To make a small batch of cochineal varnish, one needs at least 250 grams of the best cochineal.

At the time Antonio Stradivari started working in Cremona, the town was undergoing its own trials with Spain; since 1524 it had been under Spanish rule, and suffered the weight of Spanish occupation and taxation. Stradivari’s fortunes received a boost, however, in 1686 when Cardinal Orsini, Archbishop of Benevento, took possession of a cello and two violins to be presented to the Duke of Natalona. The cardinal (later Pope Benedict XIII) was so pleased with the instruments that he presented Stradivari with an indulgence (see The Strad, January 2018), effectively guaranteeing that any harm done to Stradivari would be considered a personal gesture against Cardinal Orsini. This privilege included exemption from prosecution by the Spanish courts.

The varnish on Stradivari’s earliest instruments closely resembles that of his mentor, Nicolò Amati. But by the mid-1680s his varnish had become strikingly more red, and was acquiring those traits that would set his work over and above that of his considerably talented contemporaries. Cochineal varnish became the signature appearance for instruments made in the Stradivari workshop. Violin makers in the shop were also allowed to use the varnish on their own work, although they were not able to take the varnish with them when they left. The best example is Carlo Bergonzi: fine, well-preserved instruments like his c.1732 ‘Spanish’ cello show the cochineal varnish, whereas those made after he left the shop do not.

Stradivari was making instruments for the wealthy and powerful that were literally the colour of money – and he was the only maker to have this incredible varnish.

Read: Stradivari varnish: Scarlet fever

Read: Carlo Bergonzi was never a wealthy violin maker – but he still used the best-quality maple ever seen

No comments yet