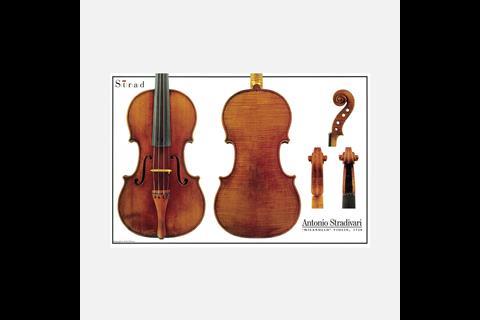

Roger Hargrave examines the Stradivari ‘Milanollo’ violin of 1728, one of the few of the master’s instruments to keep its original sharpness

This is an extract of an article first published in the May 1998 issue of The Strad

AIthough Antonio Stradivari’s workshop produced a relatively large number of fine violins, most have been considerably resculptured by the passage of time. Even where little or no damage has occurred, most of their edgework and heads have become worn through constant use. Accordingly, the image we have of Stradivari’s work is largely prejudiced by a softness of form that the master never intended. This is a major reason for the controversy surrounding some rare examples of his work which have retained something of their original sharpness.

The 1728 ‘Milanollo’ violin is a rare example of a well-preserved Stradivari. Its authenticity is unquestioned and it matches several instruments of the period, including the beautifully preserved 1727 ‘Kreutzer’ violin. The condition of the edgework and head chamfers of the ‘Milanollo’ is even finer than that of the ‘Kreutzer’, which suggests that over the centuries it has been conserved rather than played.

Although the ‘Kreutzer’ has a one-piece back, the materials which Stradivari selected for both instruments are similar beyond the point of accident. The science of dendrochronology (tree-ring analysis) can now match and date spruce and several other timbers, but unfortunately it is not yet possible to analyse maples this way. Nevertheless, it is a fairly safe bet that the back, head and rib wood of both violins came from the same tree, probably a variety of maple known as oppio. This peculiar brown speckled maple, whose narrow flames run across the back almost at right angles to the centre joint, is found on several Stradivari instruments of the period. 2 Even the spruce of the belly wood appears to match remarkably well. Certainly Stradivari preferred this kind of belly wood in his later period, when the finer-grown timers of the kind he used in the 1690s are largely noticeable by their absence.

Stradivari was 84 in 1728, but although the ‘Milanollo’ lacks the perfection of the golden period and the quality of the craftsmanship is somehow less sure, evidence of a steady hand is still apparent.

Signs of advancing age, which the instruments of the mid-1730s display, are not immediately obvious, and the quality of the ‘Milanollo’ and other instruments of the period is still way in advance of that which most of Stradivari’s younger contemporaries were producing. Nevertheless, the master’s advancing years must have been taking their toll and, if the number of surviving instruments is any indication, the production level seems to have decreased slightly from earlier times.

It must be assumed that Antonio’s two sons Francesco and Omobono, then aged 57 and 49 respectively, were heavily involved in the production of the Stradivari workshop at this time and they may have provided the steadying hand. However, as with Vuillaume’s workshop a century later, the control of the shop style was such that in this period it is extremely difficult to identify the hand of any particular individual. On several labels Antonio’s handwritten note records his age, implying that until the end of his life he was still the controlling influence. In 1727 he writes ‘fatto de Anni 83’ [made at the age of83] and in 1736 ’d’anni 92’.

The ‘Milanollo’ is available as a poster from the Strad shop with measurements on the reverse

No comments yet