Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume was the most successful French luthier of his time, but the first years of his career remain shrouded in mystery. Jonathan Marolle examines some of his earliest instruments to uncover the evolution of his technique and style

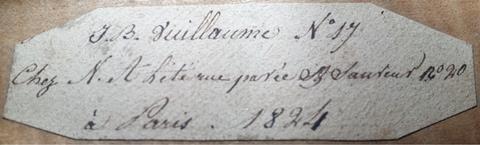

Vuillaume violin number 17 made in 1824, with spruce ’taken from an old temple of the Knights Templar’

The following is an extract from a longer article in our February 2020 issue. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The February 2020 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume is, along with Nicolas Lupot, the most famous French luthier in history. Today his instruments are sought-after and appreciated by musicians just as much as when they were first crafted in the mid-19th century – perhaps even more so. As a luthier myself, I feel a sense of pleasure every time a Vuillaume instrument appears on my workbench, and it’s heartening to note the ever-increasing interest from players and customers in the works of our illustrious predecessor. Vuillaume can accurately be called ‘a mid-19th-century maker’: his first labels are dated 1823, and he died in 1875. His career was one of incredible richness as well as resounding success, a testimony to his brilliant entrepreneurship given the turbulent times he lived through. One could say it was an almost perfect success story – although not a universal one. Despite the plethora of books and articles about the middle and later parts of Vuillaume’s career, hardly anything has been written about his early years. This short period is still a grey area for most musicians, and indeed luthiers, even though it explains much about the formative influences on the great 19th-century master.

—

Vuillaume violin number 2 from 1823

Vuillaume numbered all his instruments from 1823 onwards – a total of more than 3,000 – and the fabulous violin shown above is number 2. It is based on a Stradivari model and both the top and back plates are from one piece of wood, an almost universal characteristic of Vuillaume’s very first years. It can be interpreted as a remnant of the Mirecourt tradition: not having to join two pieces together saves a lot of time. The purfling consists of two strips of ebony (stained ‘black’ appears only much later in Vuillaume’s production) and the maple ‘white’ is placed impeccably. In the corners, the bee-stings are tilted downwards in the old-fashioned ‘crow’s beak’ style.

—

At first glance, nothing seems to distinguish violin number 17 (1824) from the rest of Vuillaume’s production from that time. The varnish is full, it is another Stradivari model, and again has a back length of 359mm. This time, though, the top and back are both in two pieces rather than one. Vuillaume himself has scribbled a note on the inside of the front, to the effect that it was ‘taken from an old temple of the Knights Templar’. A nice detail that gives an insight into the young luthier’s extracurricular activities, as well as the sometimes unusual ways of replenishing one’s wood store! Violin making history is sprinkled with instances to remind us a young luthier must be resourceful when his available wood is not always top-quality.

To read the full article by Jonathan Marolle on Vuillaume’s early years published in our February 2020 issue, click here to subscribe or login. The feature includes detailed analysis of six of Vuillaume’s numbered stringed instruments, all violins based on Stradivari models, dating from 1823 to 1828. All photography by Jonathan Marolle.

The February 2020 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

No comments yet